|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Valerie L. Katz, MD, FACS

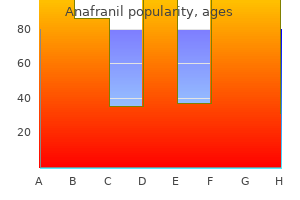

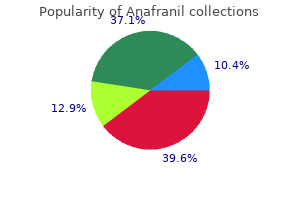

Correcting the intracranial contour is easy to accomplish depression hole definition generic anafranil 25 mg on line, but it is a nuisance when interpreting examinations clinically depression groups purchase 75 mg anafranil fast delivery. The resulting changes in the observed volumes were 1% anxiety 1st trimester cheap 25mg anafranil otc, which we think is clinically insignificant and within the range of variability reported by other segmentation algorithms25 and small in comparison with the width of the current confidence bands depression articles buy discount anafranil 50 mg. Therefore depression quest endings order 10mg anafranil amex, adjustment during clinical practice will rarely be necessary and only in borderline cases depression neurotransmitters generic 75 mg anafranil. Segmentation algorithms and tis- sue look-up tables may be improved with future releases, with slightly different volumetric results for a given dataset. Therefore, the subject being clinically assessed should be analyzed with the same software version used to create the nomograms. The patients in this data base had symptoms warranting neuroimaging, and in that context, they were not completely healthy; however, the exclusion process was extensive. We understand the advantages of developing nomograms using clinically healthy subjects; however, there are challenges. Most notably, the required sedation of healthy pediatric subjects is ethically dubious; subsequently, few articles have data in the 1- to 4-year age group. Improved segmentation algorithms are needed for patients younger than 18 months of age. The sensitivity and specificity to identify abnormalities using this method need to be determined, and a larger dataset of healthy patients would be of benefit. Rapid magnetic resonance quantification on the brain: optimization for clinical usage. Front Neurol 2016;7:16 CrossRef Medline Van Leemput K, Maes F, Vandermeulen D, et al. The accuracy of linear indices of ventricular volume in pediatric hydrocephalus: technical note. Normative pediatric brain data for spatial normalization and segmentation differs from standard adult data. Regional gray matter growth, sexual dimorphism, and cerebral asymmetry in the neonatal brain. Developmental changes in cerebral grey and white matter volume from infancy to adulthood. A quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study of changes in brain morphology from infancy to late adulthood. Statistical effects of varying sample sizes on the precision of percentile estimates. Down syndrome developmental brain transcriptome reveals defective oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Postnatal delay of myelin formation in brains from Down syndrome infants and children. Less is known regarding how variations in gestational age at birth in term infants and children affect white matter development, which was evaluated in this study. Mean diffusivity values, which are measures of water diffusivities in the brain, and axial and radial diffusivity values, which are markers for axonal growth and myelination, respectively, negatively correlated (P. No significant correlations with gestational age were observed for any tracts/regions for the term-born 8-year-old children. White matter damage in extremely or very preterm infants (32 completed weeks of gestation) is common, and increased risk is associated with lower gestational age1; white matter Received March 23, 2017; accepted after revision July 22. These studies were supported in part by United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service Project 6026-51000-010-05S and the Marion B. In addition, although white matter maturation before and after term has been investigated via imaging studies,17 there is insufficient quantitative characterization of white matter maturation during the normal term period beyond the common perception that white matter is developing rapidly during this time. In each week of gestation and/or week of life during the term period, white matter continues to mature in patterns of posterior to anterior and central to peripheral. Nor is it clear whether gestational lengths at birth of termborn infants impact this trajectory and longer-term development into childhood. The children were instructed to remain still inside the scanner, but were given a panic button for emergency use. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for these 2 research cohorts apply to this retrospective secondary analysis study. Briefly, all infants (n 44) were born to healthy women with uncomplicated singleton pregnancy; had term gestation at birth (37 completed weeks); were born with size appropriate for gestational age; and had no birth defects or congenital abnormalities and no medical issues at or after birth. All 8-year-old children (n 63) were term-born (37 completed weeks) with birth weight and current body mass index between the 5th and 95th percentile for age; were healthy with normal neurodevelopment; and had no history of neurologic impairment or injury, psychologic or psychiatric diagnoses, or any other serious illnesses or diseases. Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scales of intelligence quotient were measured, and all subjects had composite intelligence quotient 80. These voxels involved the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital cause the brain continues to develop rapidly after birth and sex lobes and the pons as well as the cerebellum. The genu, splenium, and body of the corpus callosum did not show any significant correlations. One major white matter region not displaying these significant gestation-related associations was the corpus callosum, which typically starts development at the first trimester of pregnancy with a faster growth rate than at other trimesters. To our knowledge, there is only 1 other published study focused on white matter microstructural development in term infants at young postnatal ages similar to those in our study. This may be a reflection of a "catch-up" effect (ie, the deficits presumably related to less in utero development because of shorter gestational length within the normal term period were compensated for during 8 years of postnatal development, with the white matter microstructures in term-born children with all gestational ages eventually reaching the same level). However, extensive exposure to potential confounding factors (such as diet, lifestyle, and family environment) during the 8 years of postnatal brain development could also be a mediating factor and cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor underlying the observed absence of gestational age-associated white matter differences. Although there was no significant correlation between gestational age and intelligence quotient for the 8-year-old children (r 0. One limitation for this study is that the gestational age for the 8-year-old children was parent reported. Medical records containing relevant information were not available for some subjects. Parents were asked to provide the due date (and/or the exact gestational length at birth of their children) as part of the Brain Power study (those unable to provide this information were excluded from this study), and gestational age at birth was then calculated by comparing the due date (assume 40 weeks of gestation) and the actual date of birth. Although potential inaccuracy (likely on the order of days, if any) is possible, the distribution and mean/standard deviation (Table 1) of gestational age at birth were comparable with that for the infant cohort, and therefore did not suggest apparent issues. Moderate and late preterm infants exhibit widespread brain white matter microstructure alterations at term-equivalent age relative to term-born controls. Preterm children have disturbances of white matter at 11 years of age as shown by diffusion tensor imaging. Language and reading skills in school-aged children and adolescents born preterm are associated with white matter properties on diffusion tensor imaging. White matter abnormalities and impaired attention abilities in children born very preterm. Longer gestation among children born full term influences cognitive and motor development. Gestational age and cognitive ability in early childhood: a population-based cohort study. Variation in child cognitive ability by week of gestation among healthy term births. Long-term cognitive and health outcomes of school-aged children who were born late-term vs full-term. Dietary lipids are differentially associated with hippocampal-dependent relational memory in prepubescent children. The early development of brain white matter: a review of imaging studies in fetuses, newborns and infants. White matter integrity and cognitive performance in school-age children: a population-based neuroimaging study. Consistent anterior-posterior segregation of the insula during the first 2 years of life. Gestational age and neonatal brain microstructure in term born infants: a birth cohort study. Increased dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation in obese children during observation of food stimuli. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Development of the human fetal corpus callosum: a high-resolution, cross-sectional sonographic study. Grey and white matter distribution in very preterm adolescents mediates neurodevelopmental outcome. Decreased regional brain volume and cognitive impairment in preterm children at low risk. The current literature on basion-dens interval in children is sparse and based on bony measurements with variable values. Each of the 3 attending neuroradiologists and 2 residents reviewed images in 50 different patients (n 250), and each of the 2 other residents reviewed images in 25 different patients (n 50). The patients were divided Received May 25, 2017; accepted after revision August 3. From the Department of Radiology, University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas. These measurements were obtained in sagittal reformatted images of the cervical spine in a soft-tissue window where cartilage can be easily seen around the dens (Fig 1). If cartilage was seen, then the tip of the cartilage was used for measurement (Fig 2). If the dens was completely formed and the cartilage was not seen, then the tip of the bony dens was used for measurement. The post hoc statistical tests were performed to compare which group differed from another. The interobserver reliability was measured with the intraclass correlation coefficient, which was very good, with a coefficient of 0. The data were also analyzed regarding the appearance and fusion of the os terminale ossification center. The third occipital sclerotome forms the exoccipital bone, which forms the jugular tubercle. The fourth occipital sclerotome (proatlas) divides into cranial and caudal halves, with the cranial half forming the tip of the clivus, occipital condyles, and the margin of foramen magnum. The lateral mass and superior portion of the posterior arch are formed by the caudal division of the proatlas (fourth occipital sclerotome), and the posterior and inferior portions of the arch are formed by the first spinal sclerotome. The centrum of the second spinal sclerotome forms the body of the axis, and the neural arch forms the facets and posterior arch of the axis. The chondrification of the odontoid starts from the base in stage 21 (51 days after fertilization).

Importantly bipolar depression with psychosis effective anafranil 50mg, there is no specific information on consumption of other caffeine-containing products depression uncommon symptoms buy anafranil 50mg low price. This is particularly important given the wide variability in caffeine content of popular brands of coffee mood disorder questionnaire children buy 75 mg anafranil. Furthermore depression test cyclothymia cheap 50mg anafranil mastercard, according to the same analysis anxiety yoga poses buy anafranil 75mg visa, energy drinks contribute a small portion of the caffeine consumed depression test clinical partners purchase 10mg anafranil mastercard, with major sources of caffeine being coffee, soft drinks and tea. Hamburg: We are writing in response to a March 19, 2013, letter (``the Arria Letter') to you from 18 healthcare professionals (``the Authors') concerning the safety of caffeine as an ingredient in energy drinks. The Authors of that letter assert that ``there is neither sufficient evidence of safety nor a consensus of scientific opinion to conclude that the high levels of added caffeine in energy drinks are safe. Finally, the authors conclude that ``the best available scientific evidence demonstrates a robust correlation between caffeine levels in energy drinks and adverse health and safety consequences, particularly among children, adolescents, and young adults. Mainstream energy drinks contain 10 to 15 mg/fluid ounce or about 80 to 120 mg/8 fluid ounce serving. Jack Bergman, introduced a chapter in a book on Nutritional Toxicology entitled ``Dietary Caffeine and Its Toxicity' with the following: Caffeine is part of the diet of most people. It is generally accepted that caffeine helps people work and enjoy their days a little better, but that has not been established by rigorous, objective, and quantitative studies. There is much more substantial evidence that dietary consumption is harmless in normal people. There has continued to be a perhaps never-ending series of suggestions of adverse effects which, so far, on further investigation have been shown to be illfounded. Use of the term toxicity for the effects reported or suggested for caffeine as a component of the diet, the main concern of this review, may therefore be misleading. What is toxic and what is not, what is sought after and what is an unwanted side effect, depends on the circumstances. Energy drinks have been marketed worldwide for about three decades and are safely consumed throughout the world. It is estimated that nearly 5 billion cans of energy drinks are consumed in the United States annually and many more billion cans are consumed each year worldwide. Regulatory bodies in Europe and Canada (and elsewhere) have evaluated these beverages previously and concluded that they are safe, as detailed below. Contrary to the assertion by the Authors that ``the best available scientific evidence demonstrates a robust correlation between the caffeine levels in energy drinks and adverse health consequences, particularly among children, adolescents, and young adults,' 9 the scientific evidence demonstrates that: (1) caffeine is safely consumed by virtually all consumers; (2) the effects of ``excess' caffeine consumption are self-limiting and reversible; (3) serious adverse events associated with caffeine are extremely rare and typically involve inherent, individual health-related factors beyond caffeine; and (4) for most consumers the benefits of caffeine-increased attention, vigilance, improved productivity, and concentration-are obtained without any adverse effect whatsoever. For purposes of this discussion, we will assume that ``high' means substantially in excess of the level of caffeine otherwise widely available in comparable or competing beverages such as coffee. A typical container of an energy drink will therefore contain between 80 and 240 mg caffeine. For example, a medium Starbucks Coffee (a Grande, in Starbucks parlance), which is a 16 fluid ounce beverage, contains 330 mg caffeine (Table 1). Also, shelf-stable coffees and iced coffees are sold in retail outlets on shelves and in refrigerators, often adjacent to energy drinks. Indeed, some coffee flavored ice creams and 6 Lumin Interactive (Designer), How Coffee Changed America (Web Graphic), available at newswatch. It is therefore clear that energy drinks do not introduce new or alarming levels of caffeine into the food supply, as has been suggested by the Authors of the Arria Letter. Further, while the Arria Letter states that ``many energy drinks and related products containing added caffeine exceed the caffeine concentration of even the most highly caffeinated coffee,' 16 the data in Table 1 regarding caffeine content of coffee make clear that this statement is not correct. The Authors of the Arria Letter suggest a distinction between ``naturally occurring' caffeine and ``added' caffeine, implying somehow that ``added' caffeine is more problematic. The body identifies and processes added caffeine, from any source, in the same way that it processes caffeine that may be naturally occurring in foods and beverages. Significantly, manufacturers who add caffeine to their products can control the amount to a far greater extent than producers or marketers of food in which caffeine is naturally occurring such as tea or coffee. An energy drink manufacturer can ensure with a high degree of precision and accuracy that its products contain the amount of caffeine declared on their labels. By contrast, the caffeine content of 12 the amounts used in Table 1 correspond to typical serving or container sizes. Where multiple size containers are offered for sale (coffee products, for example), the mid-sized container was used. Roland Griffiths, recently stated that ``caffeine is caffeine,' (quoted in Hill, M. Indeed, one well-cited study found that the caffeine content of one specific coffee (Starbucks Breakfast Blend) at a single coffee shop varied by hundreds of milligrams (from 259 to 564 mg in a 16 fl. By contrast, energy drinks are typically carbonated, sweetened drinks that are served cold and consumed more rapidly. Moreover, the Authors fail to account for the difference in caffeine content between coffee and energy drinks. As noted, a medium 16 fluid ounce premium coffee contains twice the amount of caffeine found in a 16 fluid ounce serving of energy drinks, negating any discrepancy that might arise from differences in the rate of consumption. In any case, the human body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes caffeine in the same exact manner regardless of whether it is delivered to the stomach cold or hot. Even if the purported differences asserted by the Authors are correct, there is no scientific evidence provided or available that establishes that sipping coffee or drinking an energy drink changes caffeine absorption from the gut in a meaningful manner, or that different manners of ingesting caffeine-containing beverages alter the metabolism of caffeine in the body. Given the pharmacokinetic parameters of caffeine, oral administration of equal doses over a short window (five minutes, for example) as opposed to an extended window (30 minutes, for example) would have a negligible effect on serum levels. When an evaluation of concentrations achieved (instantaneous intravenous administration versus 5 minute ingestion time versus 30 minute ingestion time) after a 240 mg dose of caffeine is given, using the following accepted pharmacokinetic assumptions and models, only nominal differences in concentration are revealed. The model used above does have limitations but generally demonstrates that rate of input is not a major factor in determining peak serum concentrations. This is because caffeine is well absorbed within about 45 minutes, and has a half-life of about 5 hours. A fatal acute dose of caffeine in adult humans is estimated to be between 10 and 20 g. Conversely, toxic doses are more readily achieved with consumption of caffeine tablets. In sum, the foregoing data and information document that mainstream energy drinks are not ``high' in caffeine relative to other common caffeine-containing beverages and foods, and there is no genuine difference in how the human body absorbs caffeine from coffee or other foods or from energy drinks. For example, it states ``65 percent of energy drink consumers are 13- to 35-year-olds,' 26 yet the Arria Letter does not further identify which age groups within that very broad age range are the frequent and infrequent consumers of energy drinks. Nor does it identify how many energy drinks were consumed by a specific age group during any particular time period. The Arria Letter includes several additional statements related to adolescent consumption of energy drinks: (1) ``More recent reports show that 30 to 50 percent of adolescents and young adults consume energy drinks'; (2) ``35 percent of eighth graders and 29 percent of both tenth and twelfth graders consumed an energy drink during the past year'; and (3) ``18 percent of eighth graders reported using one or more energy drinks every day. On the contrary, the fact that 30 to 50 percent of adolescents ``consume' energy drinks is vague and could mean a consumption of only one energy drink during the period of time in question. Similarly, the second statement shows only that over the course of one year 35 percent of eighth graders and 29 percent of tenth and twelfth graders consumed at least one energy drink. Therefore, the amount of energy drinks consumed by younger people is not a cause for alarm. The Somogyi study cited a recent, nationwide survey of 2,000 nationally representative households, which concluded that 0. Somogyi noted that ``[r]eliable consumption data for habitual energy drinkers are unavailable' for any age group. These researchers again found that Americans consume the bulk of their caffeine from coffee and soft drinks, and not from energy drinks. Specifically with respect to energy drinks, the researchers determined that ``[t]he percentage of energy drink users was low (<10 percent) and these beverages were minor contributors to overall caffeine intakes in all age groups. In contrast, the Authors cite one of their own articles to suggest that 30 percent to 50 percent of adolescents and young adults consume energy drinks. The levels of consumption cited in that 2011 Seifert report do not provide any insight, however, into regular energy drink consumption. One 2007 source cited by the 2011 Seifert report found that 28 percent to 34 percent of teens and young adults reported ``regularly consuming' energy drinks but did not define ``regular consumption. In fact, the German study concluded that all young people in Germany knew about energy drinks but that they actually consume them moderately, and that they prefer cola drinks. While Seifert asserts that ``[m]ost children in the study consumed energy drinks in moderation but a small group consumed extreme amounts,' that ``small group' appears to have been comprised of just three out of 1265 survey participants who said they consumed 32 oz. As detailed below, the bulk of the scientific literature does not provide a ``robust correlation' between caffeine levels in energy drinks and adverse health effects, nor does it show that children are uniquely susceptible to caffeine effects. To the contrary, as detailed below, the weight of the published, peer-reviewed scientific and medical literature supports the conclusion that consumption of mainstream energy drinks is not associated with such health risks. That is, this recommendation applied to coffee, tea, and caffeinated sodas, as well as energy drinks. Further, the potential effects described, such as physical dependence and withdrawal, were not unique effects on children and adolescents but were the same as those experienced by adults. Notably, the authors of that article acknowledge that caffeine has been shown to enhance physical performance in adults by increasing aerobic endurance and strength, improving reaction time, and delaying fatigue, though they state that these effects have not been studied in children and adolescents. Thus, it appears the view of these authors may have been skewed by a misperception of the caffeine content of typical energy drinks. Similarly, the Authors selectively quote from or interpret the study by Kaplan, Greenblatt, Ehrenberg et al. The Authors fail to note that the referenced paper cites cognitive and performance improvement at the 250 mg dose with some unpleasant effects at the higher dose. Importantly, the authors of the cited study conclude that ``the unfavorable and somatic effects, as well as performance disruption, from high doses of caffeine may intrinsically limit the doses of caffeine used in the general population. Caffeine in low to intermediate doses produces favorable effects while higher doses tend to be perceived unfavorably and are not associated with consistent enhancement of performance which, in turn, results in self-regulation of intake. The Arria Letter also asserts that the accumulation of caffeine metabolites could compound the ``negative effects of caffeine at high blood levels. While selectively quoting from a limited set of articles, the Authors fail to reference any of the authoritative publications confirming the safety of energy drinks and of caffeine at levels delivered by energy drinks for adolescent as well as adult consumers. For example, energy drinks have been reviewed by European food safety authorities on three occasions spanning a decade, and have been found to be safe, including for young consumers. Caffeine is one of the most widely studied ingredients in the food supply and has been the subject of clinical and other research for decades. Consequently, there are hundreds of peer-reviewed, published studies confirming the safety, function, and pharmacology of caffeine. Included below are examples of the body of evidence on the safety of caffeine as determined by scientists and governmental or other authoritative bodies. Caffeine Effects are a Function of Body Weight, Not Age the substantial body of scientific and medical literature demonstrates that: (1) children and adolescents experience no particular or unique safety effects from caffeine; (2) dose response is always a function of body weight (mg/kg), not age; and (3) any behavioral or other effects adolescents may experience from caffeine are the same as those experienced by adults. These levels of caffeine are comparable to , or higher than, those found in mainstream energy drinks. The following examples from the published, peer-reviewed scientific and medical literature also demonstrate that caffeine metabolism and caffeine effects are dependent on body weight, not age. For example, the term ``teenagers' captures 13- to 19-year-olds, yet a 13-year-old typically weighs considerably less than a 19-year-old. The Authors also make the argument that the safety of caffeine should take into consideration ``individuals having varying sensitivities to caffeine' rather than on ``healthy' individuals. For example, peanuts and eggs are not deemed harmful even though allergic consumers may have serious or even life-threatening reactions to these ingredients in a food. These ingredients are not deemed unsafe but rather must be declared where present over 10 ppm, even if used only as incidental additives. Rather, such sensitivities are managed through labeling, which enables caffeine-sensitive individuals to manage their caffeine consumption. American Beverage Association member companies voluntarily declare the caffeine content from all sources on the label of their energy drinks. Alleged Fatalities and Injuries the Authors assert, as a preface to a discussion of alleged fatalities and injuries associated with energy drinks, that the absence of a systematic system to ascertain the prevalence of possible adverse events related to energy drinks properly leads to the conclusion that the available data understate the actual occurrence of adverse events. It is just as plausible that the existing data overstate the occurrence of adverse events reasonably attributed to energy drinks. When one considers the fact that nearly 90 percent of North Americans consume caffeine with regularity,72 the notion that a small number of deaths in people consuming caffeine-containing beverages must have been caused by those beverages is non-defensible on its face. The overwhelming body of knowledge regarding caffeine clearly demonstrates that its use is at best a healthy activity, and at worst neutral. Additionally, specific to energy drinks, there are no data nor is there a plausible suggested mechanism by which any of the commonly utilized additives and additional ingredients would cause any form of toxicity. The Authors identify the case of 14-year-old Anais Fournier who died of a cardiac arrhythmia to try and establish a link between energy drinks and the fatality. According to the body of scientific and medical literature on normal caffeine metabolism, the caffeine from the first beverage would have completely dissipated by the time she drank the second beverage 24 hours later. Fournier is a tragedy, there is simply no scientific or medical basis upon which to conclude that the levels of caffeine in mainstream energy drinks are unsafe when consumed in accordance with the labels of those products. The Authors also reference an unpublished paper, co-authored by one of the Authors, in support of the conclusion that there has been a greater incidence of accidental ingestion of caffeine from energy drinks than other forms of caffeine in children under 6 years of age. For example, the report did not track the energy drink brands consumed or provide estimates of amounts of caffeine consumption. In more than half of the visits in which energy drinks were reportedly consumed by 18-to 25-year olds, the subjects also reported using alcohol and other drugs (and this figure is likely an underestimate given that alcohol and drug use was self-reported and thus likely underreported). Cardiovascular Effects the Authors discuss several adverse cardiac effects in children associated with ``consumption of highly caffeinated energy drinks,' such as elevated blood pressure, altered heart rates, and severe cardiac events, yet none of the studies they cite to that reportedly demonstrate adverse cardiac effects of energy drinks were conducted in children.

Invasive alien species have altered evolutionary trajectories and disrupted many community and ecosystem processes depression bipolar support alliance buy 75 mg anafranil with visa. In addition mood disorder jesse jackson generic anafranil 75mg with mastercard, they can cause substantial economic losses and threaten human health and welfare human depression definition generic anafranil 10 mg online. Today invasive species constitute a major threat affecting 30 percent of globally threatened birds depression genetic test buy cheap anafranil 25mg, 11 percent of threatened amphibians and 8 percent of the 760 threatened mammals for which data are available (Baillie bipolar depression and pregnancy anafranil 25 mg low price, Hilton-Taylor and Stuart mood disorder onset 25mg anafranil visa, 2004). The contribution of the livestock sector to detrimental invasions in ecosystems goes well beyond the impact of escaped feral animals. Animal production has also sometimes driven intentional plant invasions (for example, to improve pastures). On a different scale grazing animals themselves directly produce habitat change facilitating invasions. Movement of animals and animal products also makes them important vectors of invasive species. Livestock have also been a victim of alien plant species invasions in degrading pasture land, which may in turn have driven pasture expansion into new territories. Under this definition livestock can be considered as alien species that are invasive, particularly when little attempt is made to minimize the impact on their new environment, leading to competition with wildlife for water and grazing, the introduction of animal diseases and feeding on seedlings of local vegetation (feral animals are among the main threats to biodiversity on islands). One of the best documented effects of invasivespecies is the dramatic impact of mammalian herbivores, especially feral goats and pigs, on 4 issg. As invasive alien species, feral animals also contribute to biodiversity loss at the continental level. Nearly all livestock species of economic importance are not native to the Americas, but were introduced by European colonists to the Americas in the sixteenth century. Many harmful feral populations resulted from these introductions and the often very extensive patterns of management. Despite the negative impact of some introduced species, exotic vertebrates continue to be imported. Government agencies are gradually becoming more cautious, but they continue deliberately to introduce species for fishing, hunting and biological control. The pet trade is perhaps the single largest source of current introductions (Brown, 1989). The contribution of the livestock sector to current vertebrate introductions is currently minimal. Seed dispersal by vertebrates is responsible for the success of many invaders in disturbed as well as undisturbed habitats. Grazing livestock have undoubtedly contributed substantially to seed dispersal and continue to do so. An interesting exception is the detailed analysis of the impact of the increased demand for wool in the early twentieth century. By July 2006, the disease had affected the poultry industries in 55 countries; 209 million birds were killed by the disease or had to be culled. The widespread simultaneous occurrence of the disease poses a substantial risk of a potential disruption to the global poultry sector (McLeod et al. Wild aquatic birds of the world were only known as natural reservoirs of low pathogenic influenza A. Bird migratory patterns annually connecting land masses from the northern and southern hemispheres (including the African-Eurasian, Central Asian, East Asian- Australasian and American flyways) may contribute to the introduction and to Map 5. In particular, migratory wild birds were found positive in many European countries with no associated outbreaks in poultry (Brown et al. On the other hand wild bird populations could possibly be contaminated and impacted by infected poultry units. Historically, livestock played an important role in the transmission of disease organisms to populations that had no immunity. The introduction of rinderpest into Africa at the end of the nineteenth century devastated not only cattle but also native ungulates. The introduction of avian pox and malaria into Hawaii from Asia has contributed to the demise of lowland native bird species (Simberloff, 1996). In less than 300 years (and mostly only some 100 years) much of the temperate grassland outside Eurasia has been irrevocably transformed by human settlement and the concomitant introduction of alien plants. Clearly, livestock production was only one among many other activities driving the largely unintentional trans-Atlantic movement of alien species. However, large ruminants are considered to have largely enhanced the invasive potential of these species. According to Mack (1989), the two quintessential characteristics that make temperate grasslands in the New World vulnerable to plant invasions are the lack of large, hooved, congregating mammals5 in the Holocene or earlier, and the dominance by caespitose grasses (which grow in tussocks). The morphology and phenology of such grasses make them vulnerable to livestock-facilitated plant invasions: the apical meristem becomes elevated when growth is resumed and is placed in jeopardy throughout its growing season to removal by grazers, while these grasses persist on site exclusively through sexual reproduction. In caespitose grasslands trampling can alter plant community composition by destroying the 5 the only exception are enormous herds of bison that were supported on the Great Plains of North America, yet these large congregating animals occurred only in small, isolated areas in the intermountain west. The phenology of caespitose grasses may account for this paucity of bison (Mack, 1989). In both vulnerable grasslands in western North America the native grasses on zonal soils are all vegetatively dormant by early summer when lactating bison need maximum green forage. Once European settlers arrived, alien plants began to colonize these new and renewable sites of disturbance. Whether through grazing or trampling, or both, the common consequence of the introduction of livestock in the three vulnerable grasslands were the destruction of the native caespitose grasses, dispersal of alien plants in fur or faeces, and continual preparation of a seed bed for alien plants. Even today, New World temperate grasslands are probably not yet in a steady state, but are certain to experience further consequences from existing and new plant invasions (Mack, 1989). Livestock-related land-use changes continue, as do their impacts on biodiversity through habitat destruction and fragmentation. These areas are often rich in alien invaders, some of them deliberately introduced. Planned invasions have taken place in vast areas of tropical savannah, often assisted by fire. With the exception of some savannahs of edaphic origin, the grassland ecosystems in Africa usually result from the destruction of forest or woodland. They are often maintained through the use of fire regimes and are frequently invaded by alien species (Heywood, 1989). Likewise, in South America, the region of the great savannahs, including the cerrados and campos of Brazil, and the llanos of Colombia and Brazil have become increasingly exploited leading to invasion by weedy and pioneer species. Many of the ranch lands of South America were established on previous forest land after the European-led colonization. Similarly, in Madagascar vast areas of the natural vegetation have been burned since Palaeo-Indonesians invaded the island, to provide pasture land for zebu cattle, and are burned annually. These pastures are now largely devoid of trees and shrubs and low in biodiversity and characterized by weedy species (Heywood, 1989). These include many thistle species found on most continents (see the case of Argentina in Box 5. In California, Star Thistle was introduced during the gold rush as a contaminant of alfalfa. By 1960 it had spread to half a million hectares, to 3 million hectares by 1985, and nearly 6 million by 1999 (Mooney, 2005). It alters the ecological balance, particularly through depletion of water, and degrades pasture value. A grass that is widespread and used for permanent pastures in various parts of the tropics is Axonopus affinis. The replacement of native pastures by Lantana is threatening the habitat of the sable antelope in Kenya and Lantana can greatly alter fire regimes in natural systems. It is toxic to livestock (in some countries, it is therefore planted as a hedge to contain or keep out livestock). At the same time it benefits from the destructive foraging activities of introduced vertebrates such as pigs, cattle, goats, horses and sheep creating micro habitats for germination. It has been the focus of biological control attempts for a century, yet still poses major problems in many regions. In the Origin of Species (1872) Darwin remarked that the European cardoon (Cynara carrelated plant invasions. The transformation of the pampas from pasture to farmland was driven by immigrant farmers, who were encouraged to raise alfalfa as a means of raising even more livestock. This transformation greatly expanded the opportunity for alien plant entry and establishment. Towards the end of the nineteenth century over 100 vascular plants were listed as adventive near Buenos Aires and in Patagonia, many of which are common contaminants of seed lots. Marzocca (1984) lists several dozen aliens officially considered as "plagues of agriculture" in Argentina. While the massive transformation of Argentinean vegetation continues, the globalizing livestock sector recently drove yet another revolution of the pampas. In 1996 a genetically modified soybean variety entered the Argentinean market with a gene that allowed it to resist herbicides. Other important factors contributed to the success of what is now called "green gold". Rates of deforestation now exceed the effect of previous waves of agricultural expansion (the so-called cotton and sugarcane "fevers") (Viollat, 2006). Over the undulating plains, where these great beds occur, nothing else can now live. Von Tschudi (1868) assumed that the cardoon arrived in Argentina in the hide of a donkey. Many early plant immigrants probably arrived with livestock, and for 250 years these flat plains were grazed but not extensively ploughed (Mack, 1989). Cardoon and thistle were eventually controlled only with the extensive ploughing of the pampas at the end of the nineteenth century. Much of the genetic erosion of such staple crops occurred as a consequence of the Green Revolution, while currently there is substantial controversy around the effects to be expected from modern genetic engineering. Evidence is insufficient, but there exists strong societal concern about the possible contamination of conventional varieties by genetically modified ones, a mechanism that could be considered as "invasion". Similar concern exists for soybean, mainly cultivated for feed, because in countries such as the United States and Argentina (Box 5. Some mammal species are also harvested for medicinal use, especially in eastern Asia. The livestock sector affects overexploitation of biodiversity mainly through three distinct processes. Competition with wildlife is the oldest and renown problem, which often leads to reduction of wildlife populations. More recent processes include overexploitation of living resources (mainly fish) for use in animal feed; and erosion of livestock diversity itself through intensification and focus on fewer, more profitable breeds. Competitionwithwildlife Herder-wildlife conflicts Conflicts between herders and wildlife have existed since the origins of livestock domestication. The competition arises from two aspects: direct interactions between wild and domesticated animal populations and competition over feed and water resources. During the origins of the domestication process the main threat perceived by herders was predation by large carnivores. This led to large carnivore eradication campaigns in several regions of the world. Over-exploitation has been identified as a major threat affecting 30 percent of globally threatened birds, 6 percent of amphibians, and 33 percent of evaluated mammals. It is believed that when mammals are fully evaluated for threats, overexploitation will prove to affect an even higher percentage of species (Baillie, Hilton-Taylor and Stuart, 2004). Among mammals threatened by over-exploitation, larger mammals, especially ungulates and carnivores, are particularly at risk. In Africa, these tensions have led to a constant pressure on lion, cheetah, leopard and African wild dog populations. Conflicts between herders and predators still persist in regions where extensive production systems are predominant and where carnivore populations still exist or have been reintroduced. This is the case even in developed countries, even though the predation pressure is lower and herders are usually compensated for their losses. In France, for example, the reintroduction of the wolf and the bear in the Alps and Pyrenees has led to intense conflicts between pastoral communities, environmental lobbies and the government. In sub-Saharan Africa, especially in East and Southern Africa, production losses from predation can be an economic burden to local communities. Even if the national economic impact remains negligible, the local and individual impact can be dramatic, particularly for poor people (Binot, Castel and Canon, 2006). Predation pressure, and negative attitudes to predators among local populations, is worsening in the surroundings of the National Parks in developing countries, especially in East Africa. On the one hand, many of the protected areas are too small to host viable populations of large carnivores, as these populations often need vast hunting territories and so are forced to range outside of the parks. For example, the African wild dog in Africa has a hunting territory that extends over 3 500 km2 (Woodroffe et al. On the other hand, as land pressure mounts and traditional rangelands are progressively encroached by cropping, herders are often forced to graze their animals in the direct vicinity of the national parks. During dry seasons the surroundings of the national parks which are rich in water and palatable fodder, are often very attractive to the herders. Another source of intensifying conflict is that, as populations of wild ungulates are shrinking, wild predators are forced to look for other prey. Livestock do not represent a food of preference for the large carnivores, but they are easily accessible and large carnivores can get used to them.

While elected politicians and senior officials may have a strong affect on the definition of problems mood disorder medications for children discount 75mg anafranil with visa, and the final decisions anxiety yawning symptoms discount anafranil 75mg otc, civil servants and other policy specialists play a larger part in the coordination depression test in urdu anafranil 50 mg on-line, selection and presentation of solutions depression symptoms mnemonic trusted anafranil 50mg. Since policymakers do not have the time to devote to detailed policy work mood disorder secondary to tbi trusted anafranil 25 mg, they delegate it to civil servants who consult with interest groups definition of depression in economics generic 50 mg anafranil with amex, think tanks and other policy specialists to consider ideas and produce policy solutions. In turn, policymakers decide which problems they deem most worthy of their attention. Therefore, the strategy of interest groups or policy proponents is either to create enough interest in policy problems to lobby for a solution, or to wait for the right moment in politics that gives them the best chance to promote their solution. If the motive and opportunity of decision makers to translate ideas into action is temporary, then it limits the time to find policy solutions when a new policy problem has been identified: `When the time for action arrives, when the policy window. This window of opportunity for major policy changes opens when: Separate streams come together at critical times. A problem is recognized, a solution is developed and available in the policy community, a political change makes it the right time for policy change, and potential constraints are not severe. For example, a policy problem may suddenly appear to be a crisis requiring immediate resolution, a policy advance could make a problem solvable and therefore more worthy of attention, or a change of government could open up avenues of influence for policy entrepreneurs (1984: 21; 204; 9780230 229716 12 Ch11 06/07/2011 14:25 Page 238 Proof 238 Understanding Public Policy Box 11. Rather, the existing medical paradigm has extended into this new sphere of policy. Third, rather unusually, this extension involved the breakdown of a policy monopoly from within to foster a new monopoly in the future. In other words, the medicalscientific profession encouraged widespread debate to ensure the necessary public and governmental support for an extension of its work. However, if they do not, then each factor can act as a constraint to further action (1984: 19). Or, the problem may appear intractable, with solutions deemed ineffective or too expensive. The point is that the use of particular ideas to define and solve policy problems is far from a straightforward process. Therefore, to explain the adoption of ideas we must explore the particular circumstances in which policy change takes place. In other words, even when major policy change is likely to take place, the final outcome is rather unpredictable. It depends on factors such as the ability of the public to remain involved, the ideas available to solve 9780230 229716 12 Ch11 06/07/2011 14:25 Page 239 Proof the Role of Ideas 239 the problem, and the spirit of compromise in the political stream (1984: 186). There is an almost infinite number of ideas which could rise to the top of the political agenda, producing competition to dedicate political time to one idea at the expense of the rest. This is unlikely to occur in a parliamentary system in which one party of government dominates proceedings (Page, 2006: 208). This move in 1984 created a strong precedent for the idea of privatization which provided political rewards to a government keen to reduce public sector spending, encourage popular capitalism (through shareholding) and challenge public sector unions (2003: 34). In turn, the focus on serendipitous reasons for policy change can be reinforced by showing the obstacles to other policy changes in similar circumstances. For example, the sale of British Rail took place almost a decade later because the couplings which took place in a series of policy windows produced different results: in 1979 it produced a more limited solution (the sale of subsidiary companies) when the idea of privatization was not fully developed; in 1982 the problem of union strike action (and the effect this would have on any share issue) replaced the problem of public subsidy; and in 1987 the government no longer had the same need to raise money (Zahariadis, 2003: 79). Then a series of major accidents in the late 1980s shifted attention to rail maintenance and safety (which privatization could not solve). Zahariadis (2003) shows how problems, solutions and politics are coupled in different ways in different countries. For example, in the case of French telecoms, the problem was different: there were no equivalent budget problems (indeed, French telecoms were seen largely as a success), no equivalent split from post office, and no drive to challenge the industrial opposition to telecoms privatization. While a window for privatization was opened up by the political stream following the appointment of Jacques Chirac as Prime Minister in 1986, telecommunications did not join the list of 65 businesses sold. The French government was receptive to different ideas on the benefits of privatization, as a way to ensure the state is not overstretched (and not engaging in excessive subsidies for failing businesses) rather than as a way to roll it back (2003: 38). Instead, the French government liberalized the industry as a 9780230 229716 12 Ch11 06/07/2011 14:25 Page 242 Proof 242 Understanding Public Policy way to encourage competition. The legacy of Nazi abuses of the state produced a lower propensity to nationalize industries, with successive German governments preferring to maintain a minority stake in a range of companies. Conclusion the role of ideas is important and its discussion within political science undoubtedly improves our ability to explain complex policy events and outcomes. However, the ideas literature has the potential to confuse, for four main reasons. While an idea may be defined as a shared belief, in practice we find that the ideas literature describes a wide range of social practices. Therefore, for our purposes it is important to identify common themes, such as the extent to which ideas explain political behaviour and the links between ideas and power. Second, ideas can represent independent or dependent variables; the main source of explanation or the object to be explained. Yet, in practice the links between ideas and interests are impossible to separate completely. As a consequence, attempts to separate analytically the explanatory power of ideas, and identify the causal processes involved, may paint a misleading picture. Descriptions of the role of ideas in public policy do not make sense unless they are accompanied by descriptions of the ways in which political actors accept, reproduce or make use of them. Third, in our discussion of coalitions, paradigms and punctuations we have encountered two main types of explanatory power for ideas. On the one hand, ideas command considerable explanatory power: a paradigm 9780230 229716 12 Ch11 06/07/2011 14:25 Page 243 Proof the Role of Ideas 243 which becomes institutionalized can constrain and facilitate political behaviour for decades. Indeed, the consequence of the dominance of one idea is that the vast majority of ideas are rejected or receive no attention. This gives us a dual picture of ideas: as important, sweeping everything aside and then setting the policy direction for decades, or as unimportant, since a very small number act in this way at the expense of the rest. Most ideas are as likely to reach their final destination as sperm in the fallopian tubes, but the acceptance of a small number of ideas may have a profound effect on public policy. On the one hand, a focus on ideas signals a shift of focus from elitism to pluralism; from the power of a small band of elites towards a much wider range of experts and commentators engaged in the production of, and argumentation about, ideas (John, 1998: 156). Elected policymakers may not monopolize power because they are influenced by wider ideas which are outside of their control and prompt them to justify their behaviour in terms of discourse acceptable to the public. The use of ideas to establish policy monopolies suggests that other, unelected, elites operate under a cloak of anonymity for long periods. In this light, it is not surprising that multiple streams analysis emphasizes the messy and often random nature of agenda setting and decision making. This is something to bear in mind when, in Chapter 12, we extend our analysis to the transfer of ideas across political systems and sub-systems. Policy learning is a rather vague term employed to describe the use of knowledge to inform policy decisions. That knowledge can be based on information regarding the current problem, lessons from the past or lessons from the experience of others (although bear in mind that this is a political, not technical or objective, process). Policy transfer is also a rather vague term to describe the transfer of policy solutions or ideas from one place to another. Although they can be very closely related (one would hope that a government learns from the experiences of another before transferring policy) they can also operate relatively independently. For example, a government may decide not to transfer policy after learning from the experience of another, or it may transfer without really understanding why the exporting country had a successful experience. This chapter focuses specifically on policy transfer (see Chapter 10 for various discussions of learning). Policy transfer is not the only term to describe the transfer of policies and ideas. Lesson-drawing brings together the study of learning from the past as well as other countries (Rose, 1993). The literature invites us to consider what causes this convergence and who pursues such similarities (Bennett, 1991a). In some cases it involves the 244 9780230 229716 13 Ch12 06/07/2011 14:26 Page 245 Proof Policy Transfer 245 deliberate transfer of policy from one country to another (in others, governments just make similar decisions based on similar problems and ways of thinking). If so, we may ask a further series of questions, including: is the transfer of policy voluntary; which actors are involved; how much policy is transferred; and how do we explain variations in levels of transfer (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996) For example, the levels of coercion involved can vary from completely voluntary transfer, in which one country merely observes and emulates another, to coercive transfer, in which one country is obliged to emulate the example of others (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996). Transfer can involve a wide range of international actors, or merely a small professional network exchanging ideas. It can relate to the wholesale transfer of policy programmes, broad ideas, minor administrative changes or even the decision to learn negative lessons and not to follow another country. The scale of transfer and likelihood of success also varies markedly and is affected by factors such as the simplicity of policy and whether or not the values and political structures of the borrower and lender coincide. The value of a focus on policy transfer is that it helps us explain why policy changes and gauge the extent to which that change is common throughout the world (Box 12. Yet, it is also easy to overestimate its value by assuming that transfer has taken place, rather than countries just making similar judgements on similar problems. Further, we may ask if policy transfer is a theory of political behaviour or merely an umbrella term used to describe a wide range of practices (James and Lodge, 2003; Berry and Berry, 2007: 247). The focus is on policymakers seeking to learn lessons from successful countries (perhaps after they have considered their own past experiences) and then calculating what it would require to take that success home. It produces a series of questions about the nature and extent of lesson-drawing, such 9780230 229716 13 Ch12 06/07/2011 14:26 Page 246 Proof 246 Understanding Public Policy Box 12. However, the differences in policy conditions across different states, combined with varying degrees of willingness to follow the leader (according to the type of innovation and the values of policymakers in each state), creates uneven diffusion and conjures up a picture of ink diffusion in water (the spread is often uneven and unpredictable). The literature focuses not only on the process but also the patterns of diffusion; the overall spread and the speed of adoption. First, we can see this pattern of regular borrowing and lending (some innovate, others emulate) in the international policy community (below). Third, it highlights a key concern in the literature when we try to pin down the causes of emulation: does the impetus to transfer policy come from within or outside the importing region (Eyestone, 1977: 441) Finally, the diffusion literature alerts us to the possibility that policy similarities result from independent decisions based on similar domestic policy conditions rather than emulation (1977: 441). They sought to explain broad similarities with reference to worldwide industrialization: a common socio-economic project explains movement towards similarities, while political and cultural differences become much less important to explain change. A focus on this broader picture of convergence without emulation could lead to some confusion because the focus on this chapter is the more specific question of policy transfer. The more focused study of policy convergence contrasts with studies of globalization. It identifies the decisions of policymakers when they weigh up both external constraints to converge, and domestic pressures to diverge or stay different (Hoberg, 2001: 127). Bennett (1991a: 231) argues that we should not assume that emulation has taken place simply because policy convergence has taken place. More recent reviews of the literature are more sceptical about our ability to find a common thread in what is a heterogeneous field of study (Heichel, Pape and Sommerer, 2005). Yet, the breadth of study is betrayed by the unwieldy definition they are forced to produce. Policy transfer is: `the process by which knowledge about policies, administra- 9780230 229716 13 Ch12 06/07/2011 14:26 Page 250 Proof 250 Understanding Public Policy Box 12. In both cases, a parsimonious definition is elusive, with greater definitional coverage succeeding at the expense of clarity (as with most definitions). Further, the definition does not capture the focus of much of the broader convergence literature, which may be to confirm the phenomenon of convergence rather than detail the particular processes of transfer which might aid convergence (Heichel et al. Some countries tend to innovate while others emulate, so it is important to recognize a distinction between those involved in the selling of ideas and those most involved in importing them (although transfer is rarely in one direction only). It may be particularly important when we discuss the nature of transfer; the extent to which it is voluntary or coercive. Further, the decision to transfer once can establish a longer term borrowing and lending relationship. Relationships between other countries also demonstrate these phases or issue-specific patterns. To a large extent, the evidence suggests that importing countries are attracted to different programmes from different countries at different times. In some cases, it may refer to geographical similarities (explaining connections between rural states or urban conurbations of similar size).

Order anafranil 50mg online. 6 Signs You May Have Anxiety and Not Even Know It.