|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Darius J. B?gli, MDCM, FRCSC, FAAP, FACS

Adjunctive medication such as glucagonlike peptide 1 receptor agonists (104) may help individuals not only to meet glycemic targets but also to regulate hunger and food intake blood pressure medication good for kidneys safe 100mg toprol xl, thus having the potential to reduce uncontrollable hunger and bulimic symptoms blood pressure chart high systolic low diastolic 100mg toprol xl with amex. Effect of glycemic exposure on the risk of microvascular complications in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trialdrevisited blood pressure normal newborn toprol xl 50 mg with visa. Is self-efficacy associated with diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy Selfefficacy arrhythmia pronunciation order 25 mg toprol xl free shipping, outcome expectations pulse pressure in shock toprol xl 50 mg with mastercard, and diabetes selfmanagement in adolescents with type 1 diabetes blood pressure entry chart 100mg toprol xl fast delivery. The impact of sleep amount and sleep quality on glycemic control in c c Providers should consider reevaluating the treatment regimen of people with diabetes who present with symptoms of disordered eating behavior, an eating disorder, or disrupted patterns of eating. B Consider screening for disordered or disrupted eating using validated screening measures when hyperglycemia and weight loss are unexplained based on self-reported behaviors related to medication dosing, meal plan, and physical activity. Coordinated management of diabetes or prediabetes and serious mental illness is recommended to achieve diabetes treatment targets. In addition, S36 Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities Diabetes Care Volume 41, Supplement 1, January 2018 type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or youngerdUnited States, 2017. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetesd systematic overview of prospective observational studies. Newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus after acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Incretin-based therapy and risk of acute pancreatitis: a nationwide population-based case-control study. Islet auto transplantation following total pancreatectomy: a long-term assessment of graft function. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetesda meta-analysis. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. P01-138 Clinical implications of anxiety in diabetes: a critical review of the evidence base. Interventions that restore awareness of hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Elevated depression symptoms, antidepressant medicine use, and risk of developing diabetes during the Diabetes Prevention Program. Insulin restriction and associated morbidity and mortality in women with type 1 diabetes. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Topical review: a comprehensive risk model for disordered eating in youth with type 1 diabetes. E Patients with prediabetes should be referred to an intensive behavioral lifestyle intervention program modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program to achieve and maintain 7% loss of initial body weight and increase moderate-intensity physical activity (such as brisk walking) to at least 150 min/week. B Given the cost-effectiveness of diabetes prevention, such intervention programs should be covered by third-party payers. Those determined to be at high risk for type 2 diabetes, including people with A1C 5. See Section 2 "Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes" and Suggested citation: American Diabetes Association. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetesd2018. Participants were encouraged to distribute their activity throughout the week with a minimum frequency of three times per week with at least 10 min per session. A maximum of 75 min of strength training could be applied toward the total 150 min/week physical activity goal (6). The individual approach also allowed for tailoring of interventions to reflect the diversity of the population (6). Nutrition showed beneficial effects in those with prediabetes (1), moderate-intensity physical activity has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce abdominal fat in children and young adults (18,19). Breaking up prolonged sedentary time may also be encouraged, as it is associated with moderately lower postprandial glucose levels (21,22). Higher intakes of nuts (13), berries (14), yogurt (15), coffee, and tea (16) are associated with reduced diabetes risk. Conversely, red meats and sugar-sweetened beverages are associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes (8). As is the case for those with diabetes, individualized medical nutrition therapy (see Section 4 "Lifestyle Management" for more detailed information) is effective in lowering A1C in individuals diagnosed with prediabetes (17). Mobile applications for weight loss and diabetes prevention have been validated for their ability to reduce A1C in the setting of prediabetes (31). Consider monitoring B12 levels in those taking metformin chronically to check for possible deficiency (see Section 8 "Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment" for more details). Currently, there are significant barriers to the provision of education and support to those with prediabetes. Although reimbursement remains a barrier, studies show that providers of diabetes self-management education and support are particularly well equipped to assist people with prediabetes in developing and maintaining behaviors that can prevent or delay the development of diabetes (17,50). Metformin has the strongest evidence base and demonstrated long-term safety as pharmacologic therapy for diabetes prevention (45). B As for those with established diabetes, the standards for diabetes self-management education and support (see Section 4 "Lifestyle Management") can also apply S54 Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes Diabetes Care Volume 41, Supplement 1, January 2018 the Mediterranean diet on type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Effects on health outcomes of a Mediterranean diet with no restriction on fat intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intake of fruit, berries, and vegetables and risk of type 2 diabetes in Finnish men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. The effect of medical nutrition therapy by a registered dietitian nutritionist in patients with prediabetes participating in a randomized controlled clinical research trial. Exercise dose and diabetes risk in overweight and obese children: a randomized controlled trial. Using new technologies to improve the prevention and management of chronic conditions in populations. The effect of technology-mediated diabetes prevention interventions on weight: a meta-analysis. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification or metformin in preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among persons at increased risk: a systematic review for the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Diabetes prevention: interventions engaging community health workers [Internet], 2016. Effect of intensive versus standard blood pressure treatment according to baseline prediabetes status: a post hoc analysis of a randomized trial. Capacity of diabetes education programs to provide both diabetes self-management education and to implement diabetes prevention services. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetesd2018 Diabetes Care 2018;41(Suppl. E should be advised against purchasing or reselling preowned or secondhand test strips, as these may give incorrect results. Among patients who check their blood glucose at least once daily, many report taking no action when results are high or low. To be useful, the information must be integrated into clinical and self-management plans. The greatest predictor of A1C lowering for all age-groups was frequency of sensor use, which was highest in those aged $25 years and lower in younger age-groups. These devices may offer the opportunity to reduce hypoglycemia for those with a history of nocturnal hypoglycemia. E A1C reflects average glycemia over approximately 3 months and has strong predictive value for diabetes complications (39,40). Thus, A1C testing should be performed routinely in all patients with diabetesdat initial assessment and as part of continuing care. Other measures of average glycemia such as fructosamine and 1,5-anhydroglucitol are available, but their translation into average glucose levels and their prognostic significance are not as clear as for A1C. Although such variability is less on an intraindividual basis than that of blood glucose measurements, clinicians should exercise judgment when using A1C as the sole basis for assessing glycemic control, particularly if the result is close to the threshold that might prompt a change in medication therapy. Moreover, African Americans heterozygous for the common hemoglobin variant HbS may have, for any level of mean glycemia, lower A1C by about 0. Whether there are clinically meaningful differences in how A1C relates to average glucose in children or in different ethnicities is an area for further study (44,49,50). These analyses also suggest that further lowering of A1C from 7% to 6% [53 mmol/mol to 42 mmol/mol] is associated with further reduction in the risk of microvascular complications, although the absolute risk reductions become much smaller. Given the substantially increased risk of hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes trials and with polypharmacy in type 2 diabetes, the risks of lower glycemic targets outweigh the potential benefits on microvascular complications. Cardiovascular Disease and Type 2 Diabetes A1C and Microvascular Complications Hyperglycemia defines diabetes, and glycemic control is fundamental to diabetes management. Providers should be vigilant in preventing hypoglycemia and should not aggressively attempt to achieve near-normal A1C levels in patients in whom such targets cannot be safely and reasonably achieved. Characteristics and predicaments toward the left justify more stringent efforts to lower A1C; those toward the right suggest less stringent efforts. E Insulin-treated patients with hypoglycemia unawareness or an episode of clinically significant hypoglycemia should be advised to raise their glycemic targets to strictly avoid hypoglycemia for at least several weeks in order to partially reverse hypoglycemia unawareness and reduce risk of future episodes. B c c Individuals at risk for hypoglycemia should be asked about symptomatic and asymptomatic hypoglycemia at each encounter. E Glucagon should be prescribed for all individuals at increased risk of clinically significant hypoglycemia, defined as blood glucose,54 mg/dL (3. Recommendations from the International Hypoglycemia Study Group regarding the classification of hypoglycemia in clinical trials are outlined in Table 6. Severe hypoglycemia is defined as severe cognitive impairment requiring assistance from another person for recovery (76). Symptoms of hypoglycemia include, but are not limited to , shakiness, irritability, confusion, tachycardia, and hunger. Clinically significant hypoglycemia can cause acute harm to the person with diabetes or others, especially if it causes falls, motor vehicle accidents, or other injury. Young children with type 1 diabetes and the elderly, including those with type 1 and type 2 diabetes (77,82), are noted as particularly vulnerable to clinically significant hypoglycemia because of their reduced ability to recognize hypoglycemic symptoms and effectively communicate their needs. Hypoglycemia Treatment with hypoglycemia-prone diabetes (family members, roommates, school personnel, child care providers, correctional institution staff, or coworkers) should be instructed on the use of glucagon kits including where the kit is and when and how to administer glucagon. Hypoglycemia Prevention Providers should continue to counsel patients to treat hypoglycemia with fastacting carbohydrates at the hypoglycemia alert value of 70 mg/dL (3. Pure glucose is the preferred treatment, but any form of carbohydrate that contains glucose will raise blood glucose. Once the glucose returns to normal, the individual should be counseled to eat a meal or snack to prevent recurrent hypoglycemia. Teaching people with diabetes to balance insulin use and carbohydrate intake and exercise are necessary, but these strategies are not always sufficient for prevention. A corollary to this "vicious cycle" is that several weeks of avoidance of hypoglycemia has been demonstrated to improve counterregulation and hypoglycemia awareness in many patients (86). Hence, patients with one or more episodes of clinically significant hypoglycemia may benefit from at least short-term relaxation of glycemic targets. If accompanied by ketosis, vomiting, or alteration in the level of consciousness, marked hyperglycemia requires temporary adjustment of the treatment regimen and immediate interaction with the diabetes care team. The patient treated with noninsulin therapies or medical nutrition therapy alone may temporarily require insulin. Infection or dehydration is more likely to necessitate hospitalization of the person with diabetes than the person without diabetes. A physician with expertise in diabetes management should treat the hospitalized patient. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Structured self-monitoring of blood glucose significantly reduces A1C levels in poorly controlled, noninsulin-treated type 2 diabetes: results from the Structured Testing Program study. Dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare benefits and use of test strips in veterans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomised, 52-week, the use of glucagon is indicated for the treatment of hypoglycemia in people unable or unwilling to consume carbohydrates by mouth. Novel glucose-sensing o technology and hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, non-masked, randomised controlled trial. Evidence-informed clinical practice recommendations for treatment of type 1 diabetes complicated by problematic hypoglycemia. The fallacy of average: how using HbA1c alone to assess glycemic control can be misleading.

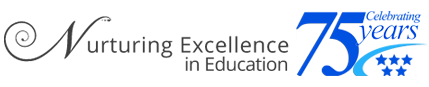

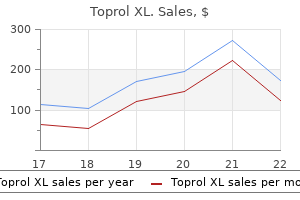

Study citations are provided for readers who wish to obtain more information on study methods and results heart attack in sleep purchase toprol xl 50 mg with amex. Similar information obtained from studies of standard fillet heart attack craig yopp discount 100mg toprol xl fast delivery, whole fish essential hypertension discount 100 mg toprol xl with visa, or other fillet types is presented in Table C-2 arteriogram cpt code buy cheap toprol xl 50 mg on-line. Both show that a high level of variability should be expected in the effectiveness of skinning blood pressure medication by class discount toprol xl 100 mg on line, trimming heart attack vs heart failure buy 50 mg toprol xl with visa, and cooking fish. Although significant variability in percent reductions was found within each study, the mean reduction data suggest that significant reductions can occur with food preparation and cooking (Voiland et al. Most of the weight reduction is due to water loss, but fat liquification and volatilization also contribute to weight reduction (Great Lakes Sport Fish Advisory Task Force, 1993). The results of studies shown in Tables C-1 through C-3 do not address chemical degradation due to heat applied in cooking. Similarities in their chemical behavior may be responsible for the similarities observed in the study results listed in Table C-3. The information provided in this table is not species-specific, which may limit the situations to which it is applicable. Summary of Contaminant Reductions Due to Skinning, Trimming, and Cooking (Based on Standard Fillet) Reduction (%)b 52 27 20 44 45 39 26 74 46 43 27 0 78 44 17 38 51 76 58 56 59 82 37 25 38 approx. Average of findings reported in New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (1981) and White et al. Chlorpyrifos pharmacokinetics and metabolism following intravascular and dietary administration in channel catfish. Bioconcentration kinetics of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in rainbow trout. Higher average mercury concentration in fish fillets after skinning and fat removal. Metal contamination in liver and muscle of northern pike (Esox lucius) and white sucker (Catostomus commersoni) from lakes near the smelter at Flin Flon, Manitoba Canada. Metabolism and disposition of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in rainbow trout. Comparison of patterns of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners in water, sediment, and indigenous organisms from New Bedford Harbor, Massachusetts. Bioconcentration and disposition of 1,3,6,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and octachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin by rainbow trout and fathead minnows. Distribution of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners and other halocarbons in whole fish and muscle among Lake Ontario salmonids. A Comparison of the Accumulation, Tissue Distribution, and Secretion of Cadmium in Different Species of Freshwater Fish. Trophodynamic analysis of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners and other chlorinated hydrocarbons in the Lake Ontario Ecosystem. Isolation and identification of two major recalcitrant toxaphene congeners in aquatic biota. Guidance for Assessing Chemical Contamination Data for Use in Fish Advisories, Volume 1: Fish Sampling and Analysis. Guidance for Assessing Chemical Contamination Data for Use in Fish Advisories, Volume 4: Risk Communication. Polychlorinated biphenyls in striped bass (Morone saxatilis) collected from the Hudson River, New York, U. Assessment of Contaminants in Five Species of Great Lakes Fish at the Dinner Table. Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin residue reduction by cooking/processing of fish fillets harvested from the Great Lakes. Pesticides and total polychlorinated biphenyls residues in raw and cooked walleye and white bass harvested from the Great Lakes. Pesticides and total polychlorinated biphenyls in chinook salmon and carp harvested from the Great Lakes: Effects of skin-on and skinoff processing and selected cooking methods. Many more people are aware of environmental issues today than in the past and their level of sophistication and interest in understanding these issues continues to increase. More and more key stakeholders in environmental issues want enough information to allow them to independently assess and make judgments about the significance of environmental risks and the reasonableness of our risk reduction actions. In order to achieve this better understanding, we must improve the way in which we characterize and communicate environmental risk. We must embrace certain fundamental values so that we may begin the process of changing the way in which we interact with each other, the public, and key stakeholders on environmental risk issues. I need your help to ensure that these values are embraced and that we change the way we do business. In doing so, we will disclose the scientific analyses, uncertainties, assumptions, and science policies which underlie our decisions as they are made throughout the risk assessment and risk management processes. I want to be sure that key science policy issues are identified as such during the risk assessment process, that policy makers are fully aware and engaged in the selection of science policy options, and that their choices and the rationale for those choices are clearly articulated and visible in our communications about environmental risk. There is value in sharing with others the complexities and challenges we face in making decisions in the face of uncertainty. Clarity in communication also means that we will strive to help the public put environmental risk in the proper perspective when we take risk management actions. We must meet this challenge and find legitimate ways to help the public better comprehend the relative significance of environmental risks. Second, because transparency in decisionmaking and clarity in communication will likely lead to more outside questioning of our assumptions and science policies, we must be more vigilant about ensuring that our core assumptions and science policies are consistent and comparable across programs, well grounded in science, and that they fall within a "zone of reasonableness. We cannot lead the fight for environmental protection into the next century unless we use common sense in all we do. These core values of transparency, clarity, consistency, and reasonableness need to guide each of us in our day-to-day work; from the toxicologist reviewing the individual cancer study, to the exposure and risk assessors, to the risk manager, and through to the ultimate decisionmaker. You need to believe in the importance of this change and convey your beliefs to your managers and staff through your words and actions in order for the change to occur. You also need to play an integral role in developing the implementing policies and procedures for your programs. I view these documents as building blocks for the development of your program-specific policies and procedures. That is, the Council will form an Advisory Group that will work with a broad Implementation Team made up of representatives from every Program Office and Region. Each Program Office and each Region will be asked by the Advisory Group to develop program and region-specific policies and procedures for risk characterization consistent with the values of transparency, clarity, consistency, and reasonableness and consistent with the attached policy and guidance. I recognize that as you develop your Program-specific policies and procedures you are likely to need additional tools to fully implement this policy. I want you to identify these needed tools and work cooperatively with the Science Policy Council in their development. I want your draft program and region-specific policies, procedures, and implementation plans to be developed and submitted to the Advisory Group for review by no later than May 30, 1995. Informed use of reliable scientific information from many different sources is a central feature of the risk assessment process. Reliable information may or may not be available for many aspects of a risk assessment. Scientific uncertainty is a fact of life for the risk assessment process, and agency managers almost always must make decisions using assessments that are not as definitive in all important areas as would be desirable. They therefore need to understand the strengths and the limitations of each assessment, and to communicate this information to all participants and the public. Additionally, the policy will provide a basis for greater clarity, transparency, reasonableness, and consistency in risk assessments across Agency programs. While most of the discussion and examples in this policy are drawn from health risk assessment, these values also apply to ecological risk assessment. A risk characterization should be prepared in a manner that is clear, transparent, reasonable and consistent with other risk characterizations of similar scope prepared across programs in the Agency. The nature of the risk characterization will depend upon the information available, the regulatory application of the risk information, and the resources (including time) available. In all cases, however, the assessment should identify and discuss all the major issues associated with determining the nature and extent of the risk and provide commentary on any constraints limiting fuller exposition. Key Aspects of Risk Characterization Bridging risk assessment and risk management. As the interface between risk assessment and risk management, risk characterizations should be clearly presented, and separate from any risk management considerations. Risk management options should be developed using the risk characterization and should be based on consideration of all relevant factors, scientific and nonscientific. To ensure transparency, risk characterizations should include a statement of confidence in the assessment that identifies all major uncertainties along with comment on their influence on the assessment, consistent with the Guidance on Risk Characterization (attached). Information should be presented on the range of exposures derived from exposure scenarios and on the use of multiple risk descriptors. In decision-making, risk managers should use risk information appropriate to their program legislation. An iterative approach to risk assessment, beginning with screening techniques, may be used to determine if a more comprehensive assessment is necessary. The degree to which confidence and uncertainty are addressed in a risk characterization depends largely on the scope of the assessment. In general, the scope of the risk characterization should reflect the information presented in the risk assessment and program-specific guidance. Risk Characterization in Context Risk assessment is based on a series of questions that the assessor asks about scientific information that is relevant to human and/or environmental risk. Each question calls for analysis and interpretation of the available studies, selection of the concepts and data that are most scientifically reliable and most relevant to the problem at hand, and scientific conclusions regarding the question presented. For example health risk assessments involve the following questions: Hazard Identification-What is known about the capacity of an environmental agent for causing cancer or other adverse health effects in humans, laboratory animals, or wildlife species Dose-Response Assessment-What is known about the biological mechanisms and dose-response relationships underlying any effects observed in the laboratory or epidemiology studies providing data for the assessment Exposure Assessment-What is known about the principal paths, patterns, and magnitudes of human or wildlife exposure and numbers of persons or wildlife species likely to be exposed Corresponding principles and questions for ecological risk assessment are being discussed as part of the effort to develop ecological risk guidelines. The risk characterization integrates information from the preceding components of the risk assessment and synthesizes an overall conclusion about risk that is complete, informative and useful for decisionmakers. Risk characterizations should clearly highlight both the confidence and the uncertainty associated with the risk assessment. For example, numerical risk estimates should always be accompanied by descriptive information carefully selected to ensure an objective and balanced characterization of risk in risk assessment reports and regulatory documents. Even though a risk characterization describes limitations in an assessment, a balanced discussion of reasonable conclusions and related uncertainties enhances, rather than detracts, from the overall credibility of each assessment. Risk communication, in contrast, emphasizes the process of exchanging information and opinion with the public-including individuals, groups, and other institutions. For example, in the case of site-specific assessments for hazardous waste sites, discussions with the public may influence the exposure pathways included in the risk assessment. While the final risk assessment document (including the risk characterization) is available to the public, the risk communication process may be better served by separate risk information documents designed for particular audiences. Promoting Clarity, Comparability and Consistency There are several reasons that the Agency should strive for greater clarity, consistency and comparability in risk assessments. For example, many people have not understood that a risk estimate of one in a million for an "average" individual is not comparable to another one in a million risk estimate for the "most exposed individual. Use of these terms in all Agency risk assessments will promote consistency and comparability. Legal Effect this policy statement and associated guidance on risk characterization do not establish or affect legal rights or obligations. Rather, they confirm the importance of risk characterization as a component of risk assessment, outline relevant principles, and identify factors Agency staff should consider in implementing the policy. The policy and associated guidance do not stand alone; nor do they establish a binding norm that is finally determinative of the issues addressed. Variations in the application of the policy and associated guidance, therefore, are not a legitimate basis for delaying or complicating action on Agency decisions. Adherence to this Agency-wide policy will improve understanding of Agency risk assessments, lead to more informed decisions, and heighten the credibility of both assessments and decisions. Implementation Assistant Administrators and Regional Administrators are responsible for implementation of this policy within their organizational units. Its responsibilities include promoting consistent interpretation, assessing Agency-wide progress, working with external groups on risk characterization issues and methods, and developing recommendations for revisions of the policy and guidance, as necessary. Each Program and Regional office will develop office-specific policies and procedures for risk characterization that are consistent with this policy and the associated guidance. Each Program and Regional office will designate a risk manager or risk assessor as the office representative to the Agency-wide Implementation Team, which will coordinate development of office-specific policies and procedures and other implementation activities. The group will work closely with staff throughout Headquarters and Regional offices to promote development of risk characterizations that present a full and complete picture of risk that meets the needs of the risk managers. The summary should include a description of the overall strengths and the limitations (including uncertainties) of the assessment and conclusions. This may be accomplished by comparisons with other chemicals or situations in which the Agency has decided to act, or with other situations which the public may be familiar with. Conceptual Guide for Developing Chemical-Specific Risk Characterizations the following outline is a guide and formatting aid for developing risk characterizations for chemical risk assessments. Similar outlines will be developed for other types of risk characterizations, including site-specific assessments and ecological risk assessments. A common format will assist risk managers in evaluating and using risk characterization. The outline represents the expected findings for a typical complete chemical assessment for a single chemical. However, exceptions for the circumstances of individual assessments exist and should be explained as part of the risk characterization. For example, particular statutory requirements, court-ordered deadlines, resource limitations, and other specific factors may be described to explain why certain elements are incomplete.

Accommodation is used to bring objects into focus; excessive accommodation may cause eyestrain blood pressure just before heart attack toprol xl 100mg cheap. They may 5 fu arrhythmia buy cheap toprol xl 100mg line, however blood pressure medication night sweats cheap toprol xl 50mg without a prescription, indicate an acquired arrhythmia jaw pain 25mg toprol xl sale, more severe underlying neurologic problem blood pressure chart 3 year old cheap 25 mg toprol xl mastercard. Specifically inquire about visual acuity hypertension treatment guidelines jnc 7 toprol xl 100mg without prescription, color vision, night vision, photophobia, abnormal head movements, tinnitus, and oscillopsia. Careful examination should yield an accurate description of the eye movements and other associated signs and symptoms. Eye movements should be initially classified as rhythmic (swinging, pendulum-like) or nonrhythmic. The waveform, direction, amplitude, frequency, and velocity of oscillations further help to classify the pattern of nystagmus. It should be noted whether the movements are symmetric or asymmetric between the two eyes. It may also be observed in children who develop blindness in the first few years of life. A thorough examination, neuroimaging, and electrophysiologic studies are usually necessary to rule out underlying ocular or neurologic disorders. Manifestations can include vertigo, ear pain, nausea, vomiting, hearing loss, and nystagmus. Inquire specifically about any recent choking episodes as well as any seasonal variation of symptoms, and relationship of symptoms to feeding. A family history for asthma (and other atopic conditions) and cystic fibrosis may be helpful. Inflammation of the large airways (tracheobronchitis) commonly occurs and is due to multiple infectious agents. These cases are typically self-limited (2 to 3 weeks) and unresponsive to antibiotics. There is an emerging recognition of a persistent or protracted bacterial bronchitis, which will respond to antibiotics and may be associated with more significant pulmonary disease. However, this diagnosis should be made with caution, particularly in children with a relatively acute history of cough. Careful consideration of other underlying pulmonary or systemic disorders should be made in children with chronic or recurring cough. The "whoop" may not occur in infants younger than 3 months of age or in partially immunized children. Conjunctival hemorrhages, upper body petechiae, and exhaustion are additional supportive symptoms; the absence of fever, myalgia, pharyngitis, and abnormal lung findings are also supportive. During epidemics or, in the case of close contact with a known case, a cough history 2 weeks is sufficient for diagnosis. Contact history is important; most cases of pertussis in infants and children can be traced to contact with a mildly symptomatic adolescent or adult whose only symptom may be a nonspecific prolonged cough. Nasopharyngeal cultures are still considered the gold standard for diagnosis; however, the sensitivity can be diminished by the fastidious nature of the organism and inappropriate handling of the specimen. Testing after antibiotic treatment and early in the course of an illness when symptoms are still fairly nonspecific is not recommended. An elevated white blood cell count (15,000 to 100,000/ml) due to lymphocytosis supports the diagnosis, although it may not occur in very young infants or immunized children. Halitosis, fever, nocturnal cough, and postnasal drip are other suggestive symptoms. Older children may experience headache, facial pain, tooth pain, and periorbital swelling. Cough due to aspiration may be produced by airway inflammation, bronchospasm, or pneumonia. If infection does occur, it is usually due to anaerobes or gram-negative organisms when chronic or nosocomial. Radionuclide scans or barium contrast studies may help to diagnose swallowing abnormalities. The intermittent nature of aspiration, however, frequently makes diagnosis difficult. The cough is described as seal-like or brassy; inspiratory stridor, hoarseness, and respiratory distress may be associated. Diagnosis should be clinical; imaging (anteroposterior and lateral neck films) should only be obtained when another diagnosis is suspected. Spasmodic croup refers to a clinically similar condition, but without evidence of airway inflammation. Episodes can resolve and recur multiple times in one night and for a few nights in a row, with the child appearing completely well in between coughing episodes. A lack of consensus exists regarding whether a spasmodic croup presentation is a distinct entity (with an allergic component) or on the 30 tic and therapeutic procedure of choice when a choking episode was witnessed, or when the history and physical are strongly suggestive of an aspirated foreign body. In the absence of a witnessed choking episode, chest films will generally be obtained to rule out other etiologies; however, only 10% to 25% of foreign bodies are radiopaque. Expiratory or lateral decubitus views may be helpful in identifying air trapping acutely but can be difficult to obtain. Aspiration of foreign bodies occurs most commonly in children under 4 years of age, with food (especially nuts) and small toys being the most commonly aspirated items. Contusions may be visible on a chest x-ray; however, initial film findings are often negative. Actual data supporting the role of reflux in chronic cough remains conflicting, except in children with neurologic impairment and a risk of aspiration. The child appears well and is typically not bothered by the coughing, even though it can frequently be significant enough to disrupt a classroom. A suggestive history, such as significant cough with colds, exercise, hard laughter, crying, or exposure to cold air, smoke, or other environmental irritants or a frequent nocturnal cough, and an improvement of symptoms to therapy. Ideally, spirometry would be used to confirm the diagnosis, although young children are typically unable to perform the testing, and normal results do not always rule out the diagnosis. Chest x-rays are not necessary in the absence of respiratory distress; however, if obtained, hyperinflation and atelectasis are common findings. The term upper airway cough syndrome (previously "postnasal drip") describes cough symptoms made worse by lying down; sinusitis and allergic rhinitis may be contributors. A history of radiation to the chest or cytotoxic medications should raise suspicions for lung disease. Use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal pain relievers can exacerbate asthma symptoms in certain people who are sensitive to these drugs. Be conscious of illicit drug use in teens (including inhalants) as a cause of chronic cough. It is associated with vocalization, as opposed to stridor, which is associated with respiration; however, the two can occur together. Hoarseness is usually benign, but evaluation is indicated for hoarseness if the onset is congenital, associated with trauma, or if it persists longer than 1 to 2 weeks. There is no clear consensus regarding when children (beyond infancy) should undergo visualization of their vocal cords for symptoms of a hoarse voice; specialists will make the decision for laryngoscopy based on the severity of hoarseness or associated symptoms, suspected diagnosis, and procedural risk. Any element of respiratory distress, tachypnea, or decreased air entry warrants visualization. Laryngeal fissures and clefts are rare conditions, but 20% of posterior fissures or clefts are associated with tracheoesophageal fistulas. Trauma related to neonatal intubation may also cause stenosis or dislocation of the laryngeal cartilages. Prolonged use of inhaled corticosteroids has been associated with Candida overgrowth. When the disorder is unilateral, it is associated with a weak, breathy cry and may lead to feeding difficulties and aspiration. In bilateral cases, stridor is more predominant and the cry may not be obviously affected. Birth trauma may also produce vocal cord paralysis because of damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Vocal cord paralysis may also be a manifestation of central neurologic disorders, including hydrocephalus, subdural hematomas, and other causes of brainstem compression. Neurologic problems are more likely to be associated with bilateral vocal cord paralysis. Lymphangiomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, and leukemic infiltrations are other etiologies. If undetected by newborn screening, presenting signs include hoarseness, constipation, prolonged hyperbilirubinemia, hypotonia, and hypothermia. A lethargic, hoarse cry is not likely to be evident until after a few months of life. Metabolic disorders cause hoarseness because of the abnormal deposition of metabolites in the airways or vocal cords. Other causes include vincristine toxicity, laryngeal edema related to congestive heart failure, and dryness due to ectodermal dysplasia, cystic fibrosis, antihistamine therapy, and psychogenic causes. The review of systems should include signs of infection and any obvious aggravating factors. Particularly important is a history of any recent choking episodes, which would raise the suspicion of a foreign body. A careful skin exam for cutaneous findings such as hemangiomas should be performed, particularly in infants in whom the stridor is gradually worsening over time. Classic features include rapid progression from a sore throat and fever to severe respiratory distress, drooling, and dysphagia. Immediate intubation in an operating room is recommended because of the high risk of complete airway obstruction. Bacterial tracheitis should be suspected when an acute clinical worsening occurs. Retropharyngeal abscesses are more common in ages greater than 5 years and are more likely to present with neck pain, torticollis, hyperextension of the neck, and cervical adenopathy. Peritonsillar abscesses are more common in older children and adolescents and are more likely to present with trismus (pain and difficulty with opening the mouth), a muffled voice, and adenopathy; asymmetrical peritonsillar bulging may be evident on exam. Nonspecific signs and symptoms may include sore throat, fever, adenopathy, drooling, and refusal to move the neck. Symptoms are characteristically worse when the infant is supine or agitated and typically resolve within the first year. Laryngomalacia is often accompanied by tracheomalacia that may cause expiratory wheezing and cough as well as stridor. Episodes can resolve and recur multiple times in 1 night and for up to 4 nights in a row, with the child appearing completely well in between coughing episodes. A lack of consensus exists regarding whether a spasmodic croup presentation is a distinct entity (with anallergic component) or on the same spectrum as infectious croup, because both have been associated with viral infections. A child with a clinical picture consistent with croup who is stable and responding well to therapy may be managed without imaging. For a child with severe respiratory distress and a clinical picture suggesting bacterial tracheitis or epiglottitis. If epiglottitis is suspected, arrangements should be made for immediate intubation in an operating room. Even if a choking or gagging episode was not observed, rigid bronchoscopy is increasingly becoming the diagnostic (and therapeutic) procedure of choice when the H and P are strongly suggestive. Aspiration of objects small enough to reach the lower airways is more likely to present with cough and wheezing. Congenital hemangiomas in a subglottic location are rare but potentially life-threatening. Symptoms usually develop between 1 and 2 months of age as gradual enlargement causes progressive airway obstruction. Cutaneous hemangiomas, particularly on the head and neck, should raise suspicion for this condition. Rarely, mediastinal lesions, thyroid enlargement, or esophageal foreign bodies may cause stridor by impinging on the larynx. Symptoms are usually worsened by crying and neck flexion; complete vascular rings may cause swallowing difficulties. Chest x-rays may suggest the diagnosis; barium Chapter 12 esophagrams can be very useful. Other causes include neurologic syndromes (ArnoldChiari malformation) and neck or chest surgery. Papillomas develop primarily in the larynx; occasional spread to other sites in the aerodigestive tract occurs in severe cases. They can develop at any time from shortly after birth to several years of age, initially presenting as hoarseness (which may go unnoticed initially) and progressing to stridor. The clinical significance of the underlying problem can range from mild to severe. The classic presentation of acute bronchiolitis begins with nonspecific cold symptoms and progresses fairly rapidly to profuse rhinorrhea, harsh cough, wheezing, and tachypnea. Parainfluenza, influenza, rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, and human bocavirus are other etiologies. The review of systems should include signs and symptoms such as fever, weight loss, night sweats, and dysphagia. Inquire specifically about any recent choking episodes and about medications (specifically inquire if the child was ever prescribed an inhaler in their past), as well as a family history of asthma and allergies. These pathogens cause more clinically significant illness in school-aged children than in younger children. Cough that progresses over the first week of illness, fine crackles and wheezes, and nonspecific x-ray findings are characteristic. Depending on the level of illness, a chest x-ray could be considered to rule out a treatable pneumonia. By definition, the diagnosis of asthma requires a history of recurrent or chronic symptoms of wheezing or airflow obstruction.

Cheap toprol xl 25mg on-line. iHealth Wireless Blood Pressure Monitor.

References