|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Andrew A. Monjan, PhD, MPH

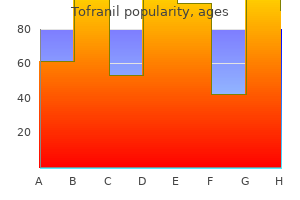

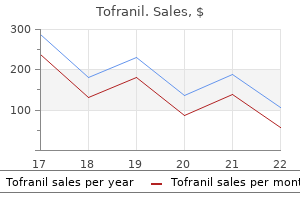

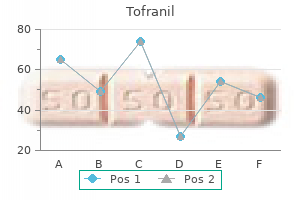

The relationship between pre-pregnancy 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 917 Part 10 Diabetes in Special Groups care and early pregnancy loss anxiety 9 months postpartum discount tofranil 25mg fast delivery, major congenital anomaly or perinatal death in type I diabetes mellitus anxiety symptoms knee pain order tofranil 50mg without a prescription. Risk of complications of pregnancy in women with type 1 diabetes: nationwide prospective study in the Netherlands anxiety genetic trusted 25mg tofranil. Personal experience of prepregnancy care in women with insulin dependent diabetes social anxiety trusted 50mg tofranil. Attitudes and knowledge regarding contraception and prepregnancy counselling in insulin dependent diabetes anxiety signs effective 25mg tofranil. The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society consensus guidelines for the management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in relation to pregnancy anxiety in dogs purchase 50mg tofranil with mastercard. Hypoglycemia: the price of intensive insulin therapy for pregnant women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Prevention of neural tube defects: the results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. The role of modifiable pre-pregnancy risk factors in preventing adverse fetal outcomes among women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The health and nutrition of young indigenous women in north Queensland: intergenerational implications of poor food quality, obesity, diabetes, tobacco smoking and alcohol use. Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in obese women: how much is enough Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines in Committee to Reexamine Institute of Medicine Pregnancy Weight Guidelines. Assessing the teratogenic potential of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in pregnancy. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk, 7th edn. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaeutical Society of Great Britain, 2007. Central nervous system and limb anomalies in case reports of first-trimester statin exposure. Hemodynamic changes associated with intravenous infusion of the calcium antagonist verapamil in the treatment of severe gestational proteinuric hypertension. The safety of calcium channel blockers in human pregnancy: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Undiagnosed coeliac disease does not appear to be associated with unfavourable outcome of pregnancy. Prevalence of nocturnal hypoglycemia in first trimester of pregnancy in patients with insulin treated diabetes mellitus. Changes in the glycemic profiles of women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes during pregnancy. Postprandial verses preprandial glucose monitoring in women with gestational diabetes mellitus requiring insulin therapy. Continuous glucose monitoring for the evaluation of gravid women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Forty-eight-hour first-trimester glucose profiles in women with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a report of three cases of congenital malformation. Effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in pregnant women with diabetes: randomised clinical trial. Twice daily versus four times daily insulin dose regimens for diabetes in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. Systematic review and meta-analysis of short-acting insulin analogues in patients with diabetes mellitus. Maternal glycemic control and hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetic pregnancy: a randomized trial of insulin aspart versus human insulin in 322 pregnant women. Is insulin lispro safe in pregnant women: does it cause any adverse outcomes on infants or mothers Outcome of pregnancy in type 1 diabetic patients treated with insulin lispro or regular insulin: an Italian experience. A comparison of lispro and regular insulin for the management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in pregnancy. Correlations of receptor binding and metabolic and mitogenic potencies of insulin analogs designed for clinical use. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion vs intensive conventional insulin therapy in pregnant women with diabetes: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trials. Analysis of outcome of pregnancy in type 1 diabetics treated with insulin pump or conventional insulin therapy. Counterpoint: oral hypoglyemic agents should be used to treat diabetic pregnant women. A 10-year retrospective analysis of pregnancy outcome in pregestational type 2 diabetes: comparison of insulin and oral glucose-lowering agents. Benefits and risks of oral diabetes agents compared with insulin in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review. Obesity, gestational weight gain and preterm birth: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Associations of gestational weight gain with short- and longer-term maternal and child health outcomes. Combined associations of prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with the outcome of pregnancy. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital cardiac anomalies: a practical approach using two basic views. Large-for-gestational-age infants of type 1 mother with diabetes: an effect of preprandial hyperglycemia Glycemic control throughout pregnancy and fetal growth in insulin-dependent diabetes. Randomized trial of diet versus diet plus cardiovascular conditioning on glucose levels in gestational diabetes. Resistance exercise decreases the need for insulin in overweight women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Insulin-requiring diabetes in pregnancy: a randomized trial of active induction of labor and expectant management. Induction of labor at 38 to 39 weeks of gestation reduces the incidence of shoulder dystocia in gestational diabetic patients class A2. Risk factors associated with preterm delivery in women with pregestational diabetes. Factors associated with preterm delivery in women with type 1 diabetes: a cohort study. Insulin dose during glucocorticoid treatment for fetal lung maturation in diabetic pregnancy: test of an algorithm [correction of analgoritm]. A protocol for improved glycemic control following corticosteroid therapy in diabetic pregnancies. Effect of management policy upon 120 type 1 diabetic pregnancies: policy decisions in practice. Watchful waiting: a management protocol for maternal glycaemia in the peripartum period. Analysis of longitudinal data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System. Breast-feeding and risk for childhood obesity: does maternal diabetes or obesity status matter Breast feeding and the risk of obesity and related metabolic diseases in the child. Prevalence and predictive value of islet cell antibodies in women with gestational diabetes. Incidence and severity of gestational diabetes mellitus according to country of birth in women living in Australia. Diabetes in pregnancy in Zuni Indian women: prevalence and subsequent development of clinical diabetes after gestational diabetes. Prepregnancy weight and antepartum insulin secretion predict glucose tolerance five years after gestational diabetes mellitus. Gestational diabetes mellitus: clinical predictors and long-term risk of developing type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study using survival analysis. Long-term diabetogenic effect of single pregnancy in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Preservation of pancreatic beta-cell function and prevention of type 2 diabetes by pharmacological treatment of insulin resistance in high-risk hispanic women. Missed opportunities for type 2 diabetes mellitus screening among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Who returns for postpartum glucose screening following gestational diabetes mellitus Efficacy and cost of postpartum screening strategies for diabetes among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus. A postnatal fasting plasma glucose is useful in determining which women with gestational diabetes should undergo a postnatal oral glucose tolerance test. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Introduction Diabetes, the most common disabling metabolic disorder, imposes considerable economic, social and health burdens [1]. Older people do not accept illness without question, however, and expect equity of access to treatment and services as for younger people. As those who are above pensionable age are, in most Westernized societies, a significant proportion of the voting public, they can be very persuasive in ensuring that there are political commitments to improving the organization and delivery of health care. Older people with diabetes use primary care services two to three times more than their counterparts Textbook of Diabetes, 4th edition. The burden of hospital care is also increased two to three times in those with diabetes compared with the general aged population [4], with more frequent clinic visits and a fivefold higher admission rate; acute hospital admissions account for 60% of total expenditure in this group [5]. Hospital admissions last twice as long for older patients with diabetes compared with agematched control groups without diabetes, with the totals averaging 7 and 8 days per year for men and women, respectively [4,6,8]. Introducing insulin treatment increases costs fourfold, both in the community and in hospital, where bed occupancy rises to 24 days per year [4]. Additional considerations that apply to the elderly population are described in the text. Subjects included those with previously diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes (defined by fasting plasma glucose 7. It must be remembered that older people with diabetes, particularly those who are housebound or institutionalized, have special needs (Table 54. By the time of publication of this edition, this number is projected to rise to 285 million. The prevalence of diabetes begins to rise steadily from early adulthood, reaching a plateau in those aged 60 years or older; the data in Figure 54. This condition appears to be most prevalent in northern Europe and is rare in Asians and Africans. There are marked ethnic and geographic differences in the prevalence rates of diabetes amongst older people. This is attributed to various combinations of insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion that result in a progressive age-related decline in glucose tolerance, which begins in the third decade and continues throughout adulthood [18,19]. Plasma glucose levels at 1 and 2 hours after the standard 75-g oral glucose challenge rise by 0. Perhaps the most important is impairment of insulin-mediated glucose disposal, especially in skeletal muscle [19,20], which is particularly marked in obese subjects (Figure 54. Insulin receptor number and binding are not consistently affected by age, and so post-receptor defects are presumably responsible. Contributory factors in some cases include increased body fat mass, physical inactivity and diabetogenic drugs such as thiazides. The ability of insulin to enhance blood flow is also considerably reduced in obese insulin-resistant subjects with diabetes; this may be etiologically important, as insulin-mediated vasodilatation is thought to account for about 30% of normal glucose disposal. The euglycemic clamp technique was used to measure the glucose disposal rate in healthy lean and obese elderly controls, and in their counterparts with diabetes. As well as insulin resistance, many elderly people with glucose intolerance show impairment of glucose-induced insulin secretion, especially in response to oral rather than intravenous glucose. Some older subjects with hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state need very small doses of insulin to reduce plasma glucose levels, although hypercatabolic or severely insulin-resistant states will require higher dosages. Thrombotic complications may occur, especially in subjects with hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state; prophylactic anticoagulation with low dose subcutaneous heparin is therefore recommended. The tendency to hyperosmolarity may be worsened in elderly people, who may not perceive thirst or drink enough to compensate for the osmotic diuresis, and are often taking diuretics [26]. Residents of care homes are at increased risk of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, which is associated with appreciable mortality [27]. Compared with the young, older patients have higher mortality and longer stays in hospital; they are also less likely to have had diabetes diagnosed previously, and more likely to have renal impairment and to require higher insulin regimens [28]. Hypoglycemia Older patients are particularly susceptible to hypoglycemia, and this problem is often exacerbated because old people may have been given little knowledge about the symptoms and signs of hypoglycemia [29]. Even health professionals may misdiagnose hypoglycemia as a stroke, transient ischemic attack, unexplained confusion or epileptic fit, as illustrated in the case history below. He was unconscious and the family was told by the emergency room staff that he had had a stroke and his prognosis was very poor. Initial investigations are as for younger patients, including arterial blood gases and plasma osmolality (see Chapter 34).

Lifetime HbA1c values anxiety zig ziglar generic tofranil 50 mg on-line, used to estimate of chronic hyperglycemia anxiety symptoms 9 dpo buy cheap tofranil 50 mg on-line, were associated with less cortical volume in the right posterior brain regions (particularly the right cuneus and precuneus) anxiety medication for children tofranil 25mg low price, also replicating findings in adults with diabetes [183] anxiety essential oils tofranil 75 mg with mastercard. Chronic hyperglycemia was also associated with less white matter anxiety symptoms eyes 75 mg tofranil overnight delivery, and these effects were most pronounced in parietal brain regions anxiety 2 months postpartum cheap tofranil 75 mg mastercard. Even when differences were detected, they were modest at best, with effect sizes (d) ranging from 0. Moreover, with only one exception ("crystallized intelligence"), virtually all of the cognitive tasks on which patients with diabetes perform more poorly were those that also required rapid responding. Remarkably, the magnitude of the cognitive differences found in these older adults was similar (d = 0. Multiple studies have also demonstrated that cerebral blood flow patterns are abnormal in adults with diabetes, with these effects greatest in frontal and frontotemporal brain regions [197]. In one large study, 85% of middle-aged adults with diabetes showed hypoperfusion in one or more region of interest compared to 10% of controls; similarly, 58% of subjects with diabetes showed hyperperfusion, compared to 20% of controls [182]. Compared with a group of healthy individuals without diabetes, young adults with a childhood onset of diabetes manifested significantly less gray matter (approximately 5%) in the right superior temporal gyrus, and in several left hemisphere regions, including the temporal gyrus, angular gyrus, medial frontal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule and thalamus [183]. These structures are especially important for attention, memory and language processing. The strongest predictor of gray matter density reduction was degree of chronic hyperglycemia in so far as higher lifetime HbA1c values were consistently correlated with lower gray matter density. Reductions in white matter volume have also been noted, with effects being greatest amongst adults with a longer history of chronic hyperglycemia and microvascular complications [199]. Subjects who had clinically significant proliferative diabetic retinopathy at study entry, or who developed retinopathy during the course of the follow-up period, showed a significant decline in psychomotor efficiency, compared to demographically similar subjects without diabetes. In contrast, those without retinopathy at either time showed no evidence of psychomotor slowing. The risk of cognitive change was predicted by four variables: the presence or development of proliferative retinopathy, the presence of autonomic neuropathy, elevated systolic blood pressure and longer duration of diabetes. The resulting statistical model identified, with 83% accuracy, subjects who showed significant cognitive decline and explained 53% of the variance. Other microvascular complications, particularly peripheral neuropathy, are also associated with changes in brain function and structure [177,193,196,203,204]. Because middle-aged adults without diabetes who have retinal microaneurysms also show a pattern of cognitive decline that is characterized by psychomotor slowing [205], it has been suggested that retinopathy may serve as a general marker of cerebral microangiopathy [148,206]. This is quite plausible, given the well-known homology between the retinal and cerebral microvascular systems [207]. In patients with clinically significant diabetic retinopathy, the resulting microangiopathy could lead to cerebral hypoperfusion and thereby contribute to the development of abnormalities in brain structure and function by interfering with the efficient delivery of glucose and other key substances to neural tissue [148,198]. The relationship often reported between peripheral neuropathy and brain dysfunction in patients with diabetes may simply reflect the fact that microvascular complications tend to appear contemporaneously and have a common origin [208,209]. That is, microvascular disease may be the primary mechanism underlying the development of neurocognitive dysfunction in young and middle-aged adults [150]. Repeated episodes of severe hypoglycemia and cognitive dysfunction the widespread belief that moderately severe hypoglycemia will induce cognitive impairment in adults with diabetes appears to have little support from a growing body of research on this topic. Lifetime rates of severe hypoglycemia, defined as including a seizure or coma, were high, with a total of 1355 episodes reported in 453 subjects over the course of the study. Despite that, no relationship whatsoever was found between the cumulative number of severe hypoglycemic episodes and performance on a comprehensive battery of cognitive tests [210]. Cross-sectional studies have also failed to find robust relationships between cognition and episodes of severe hypoglycemia [186,201]. Several earlier studies did note a link between hypoglycemia and brain damage [211], but all relied on small samples of highly selected subjects who were assessed with a limited number of cognitive tests which yielded a pattern of results that was not entirely consistent with brain damage. For example, subjects with repeated hypoglycemia performed slower, but no less accurately, on a number of tests, and earned somewhat lower scores on the Performance subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, yet learning and memory skills were intact. This latter finding is unexpected because of the well-known associations between memory and the hippocampus, a major focus of structural damage following profound hypoglycemia in rodents [212], nonhuman primates [213] and humans [184,214]. Whether moderately severe bouts of hypoglycemia adversely affect brain structure 818 Psychologic Factors and Diabetes Chapter 49 remains controversial, with some [215] but not all [174] studies finding evidence of neuronal necrosis in rodent models. In human studies it can be quite difficult to make attributions specifically to hypoglycemia, rather than to chronic hyperglycemia, because patients who experience hypoglycemia also have a history of poor metabolic control [177]. As described in Chapter 33, severe and profound hypoglycemia can induce significant structural and function brain damage, but the prevalence of this phenomenon in adults with diabetes seems extremely low. Several recent studies and review articles have noted an increased risk of dementia that ranges 1. The degree of chronic hyperglycemia, as indexed by HbA1c levels, is the best (albeit imperfect) predictor of impairment in the older patient with diabetes, although a growing body of research has identified other diabetes-related conditions, including hyperinsulinemia [239,240], hypertension [220] and hypercholesterolemia [241]. The strongest predictor of poorer cognitive function was poorer metabolic control; neither duration of diabetes nor severity of peripheral neuropathy were related to any cognitive outcome variable [226]. Other studies have also noted strong negative relationships between HbA1c values and cognition. Structural changes appeared to be more prominent in women and were associated with higher HbA1c values and older age, but were unrelated to diabetes duration, hypertension or hyperlipidemia. The medication regimen may be less onerous, but dietary and lifestyle changes are often harder to tolerate. The frequently reported absence of a strong relationship between adherence and glycemic levels may reflect the effects of physiologic characteristics, such as intercurrent illness or hormonal fluctuations secondary to puberty. Metabolic control Psychologic traits and their impact on metabolic control these encompass a series of overlapping psychologic concepts that include "personality," "temperament" and "coping style. By contrast, HbA1c values tend to be higher in adults who are opportunistic and alienated [244] or who have poor impulse control, a propensity for self-destructive behaviors and difficulty maintaining interpersonal relationships [245]. Being a worrier or highly emotional, as reflected by elevated neuroticism scores or higher levels of trait negative affect, may also be associated with poorer metabolic control [246,247], although there is not complete agreement [248,249]. Individuals who have an "internal" locus of control believe that they are responsible for their health, whereas those who have an "external" locus believe that they are at the mercy of chance, or some other outside force. One would expect that individuals with an internal locus of control would do a better job of managing their diabetes, and that this would lead to better metabolic control, yet most studies have failed to demonstrate a strong link between locus of control and adherence [252,256]. Reconciliation of these discrepancies may require a reconceptualization of the locus of control construct. For example, internal locus of control may have multiple dimensions such as autonomy and self-blame that are not typically measured in a systematic fashion yet may lead to somewhat different health outcomes [257]. Multidimensional measures that examine different aspects of sense of control as well as different modes of control and motivation for control may ultimately provide investigators with more accurate insights into the complex inter-relationships between perception of control and optimal diabetes management but, to date, they have been used only infrequently [258]. According to a systems model of health, there is no simple direct relationship between any single psychologic variable and metabolic control [242]. Rather, health outcomes are determined by a system of reciprocal relationships amongst multiple psychologic, behavioral and physiologic variables. Psychologic traits are relatively enduring characteristics that include personality, temperament and coping style. These may have a direct impact on self-care behaviors (adherence), and may also have a direct impact on emotional state. Psychologic states are more transitory and reflect emotions or feelings at a given point in time. Family functioning, including conflicts and degree of family cohesiveness, can affect psychologic state (and vice versa), but can also influence self-care behaviors. Self-care or adherence behaviors include medication use, diet, exercise and monitoring, and these 820 Psychologic Factors and Diabetes Chapter 49 low self-efficacy and high outcome expectancy tended to be in poorer metabolic control [259]. Problem-focused coping, in contrast, seeks to change the environment and thereby eliminate the threat. Within each of these categories, specific behavioral strategies may be differentially effective. Data from a meta-analysis of 21 studies have shown that the use of approach coping was associated with both better overall psychologic adjustment and with somewhat better metabolic control [264]. If traits truly reflect enduring behavioral characteristics, they ought to predict long-term adherence. Coping style assessed soon after diabetes onset predicted adherence behaviors 4 years later. Those children who used more mature defense mechanisms and showed greater adaptive capacity such as higher stress tolerance or greater persistence shortly after diagnosis were most likely to manage their diabetes satisfactorily in the long term. No experimental studies have systematically examined the relationship between chronic stress and long-term metabolic changes, and it remains possible that both indirect (behavioral) and direct (neuroendocrine) pathways are involved in mediating the relationship between heightened stress and poor metabolic control [242]. Investigators have also considered the possibility that high levels of stress may trigger the appearance of diabetes in genetically susceptible individuals [275]. Some of the strongest evidence for a link between affect and glycemic state comes from an early study in which adults with diabetes were followed during 36 weeks of treatment [287]. As glycemic control improved, symptoms of depression and anxiety declined; as control worsened, depression and anxiety increased, giving the appearance that success (or lack thereof) in managing diabetes led to corresponding changes in mood state. Taking a different approach, more recently researchers focused their attention on the extent to which changes in depressive symptomatology over a 12-month follow-up period influenced HbA1c values [288]. Although there was a marked reduction in depressive symptoms regardless of type of diabetes, there was no corresponding improvement in metabolic control over time, leading to the conclusion that mood state has no meaningful impact on metabolic control. The absence of an obvious relationship between depression and metabolic control [288] is not only counterintuitive, but it is inconsistent with the growing body of literature that suggests that the presence of depression adversely affects the medication adherence and self-care behaviors of people with diabetes. Higher levels of stress are associated with poorer glycemic control in adolescents [266,267] and adults [262,268], although there are very high levels of inter-individual variability. Given those relationships, one would expect that reducing the level of depression would lead to corresponding improvements in their metabolic control as the person with diabetes begins to take better care of themselves but, to the best of our knowledge, no data support that possibility. The only prospective data available demonstrate that the presence of depressive symptoms at baseline predicts poorer adherence 9 months later [292]. Whether adherence would improve as depressive symptoms reduce in severity remains unexamined. This pattern of results has subsequently been supported by other large prospective [305] and cross-sectional analyses [313]. Self-care or "adherence" behaviors the terms "adherence" and "compliance" have been used interchangeably, and refer to the extent to which an individual follows a medical management regimen. Because it is the patient, and not the health care professional, who is responsible for nearly all diabetes care [315], an increasing number of writers have suggested that diabetes management efficacy be assessed by determining the extent to which a patient engages in "self-care" behaviors [316,317]. The shift in terminology from "adherence" to "self-care behaviors" acknowledges the behavioral complexity of diabetes management, and takes into account recent data demonstrating that specific self-care behaviors. For example, data from a large survey of more than 2000 adults with diabetes indicated that 97% of insulin requiring patients and 93% of oral medication requiring patients always or usually took their medications as recommended, but only 77% reported that they always or usually followed blood glucose selfmonitoring recommendations, and even fewer followed diet (63%) and exercise (40%) recommendations [320]. These findings are consistent with earlier studies demonstrating that more behaviorally complex activities such as diet and exercise are performed less consistently than medication-taking and blood glucose monitoring [321]. Not all self-care activities are equally predictive of glycemic control for children or adults [314,322] but, overall, the more self-care behaviors that are performed well, the greater should be the improvement in blood glucose control [257]. Blood glucose self-monitoring frequency ought to be a particularly salient self-care activity. Data Family characteristics Diabetes can dramatically disrupt the entire family, particularly when the patient is a child or adolescent [293]. Within the family, low levels of conflict [298], including sibling conflict [299], high levels of cohesion [8,300] and better communication skills [301] are associated with better control, as is a higher level of social support from family and friends [302]. Parental marital satisfaction also predicts control [300], perhaps because it serves as a surrogate for family cohesion and lack of conflict. Family factors such as lower adherence levels associated and greater levels of family stress, more family conflict and less family cohesion and sociodemographic variables. Consistent with those data is the observation that children raised by single mothers have poorer metabolic control than those from two-parent families [307]. In adults with diabetes, better marital satisfaction is associated with better diabetes-related quality of life and marginally better glycemic control [308] but, not surprisingly, more global variables such as family [309] and work environment [310] do not predict glycemic control, although they do predict degree of psychologic adjustment. The relationship between family characteristics and glycemic control in children is most likely mediated via a purely behavioral pathway whereby family conflicts disrupt performance of selfcare behaviors. Degree of family conflict and extent of family organization at diagnosis were the best predictors of both short and long-term adherence to diet, exercise, insulin administration and self-monitoring. Younger children with diabetes tend to show better adherence (perhaps because of greater parental involvement) than adolescents [256,322]. Even after controlling for age, however, a longer duration of diabetes tends to be associated with declines in adherence [16,256], at least during adolescence. Other factors associated with better adherence are good family support [296], more shared responsibility between the child with diabetes and parent for self-care behaviors [327], greater cognitive maturity [328], more knowledge of diabetes and its management and better memory skills [319]. Doctor-centered discussions discourage patients from asking questions and increase their level of uncertainty and discomfort [330], whereas patient-centered communications are predictive of better self-reported adherence [331]. The generally weak relationship between self-care behaviors and metabolic control remains problematic for any model purporting to predict successful diabetes management. To some extent, this could reflect the possibility that the HbA1c concentration is not the most appropriate measure of metabolic control [314], but it is more likely that the unexplained variance in glycemic control reflects unspecified physiologic or situational characteristics, as well as difficulties inherent in measuring self-care behaviors [317].

It is noteworthy that most proteins released from adipose tissue are not produced by fat cells but rather by pre-adipocytes and invading immune cells such as activated macrophages anxiety symptoms for 3 months order tofranil 75mg with amex. The relative contributions of the various cellular components in adipose tissue to the secretion of these products remains unknown and may vary substantially according to depot and model anxiety 8 months postpartum order tofranil 25mg with amex. Nevertheless anxiety symptoms 3 days 75mg tofranil with amex, all these locally secreted factors appear to participate in the induction and maintenance of the subacute inflammatory state associated with obesity anxiety 6 weeks postpartum tofranil 75 mg for sale. It is also important to mention that the invading macrophages release factors that substantially augment adipocyte inflammation and insulin resistance [62] anxiety symptoms 6 week pregnancy buy tofranil 75 mg overnight delivery. Another interesting observation in this context is that pre-adipocytes and macrophages share many common features [57] anxiety symptoms teenager discount tofranil 50 mg online. The regulation and biologic functions of the secretory products are diverse and only poorly understood. In addition to the direct effects of fatty acids and their intracellular products, other factors may also contribute to the chronic inflammatory state in adipose tissue. It was recently shown that fat cell size may be a critical determinant of the production of proinflammatory and antiinflammatory factors. Enlarged hypertrophic fat cells are characterized by a shift towards a proinflammatory state [63], thereby promoting insulin resistance. Adipose tissue hypoxia An expansion of the adipose tissue mass leads to fat cell hypertrophy and subsequent hypoxia of the tissue. These consequences are also accompanied by an inhibition of adipogenesis and triglyceride synthesis and elevated circulating free fatty acid concentrations. The low oxygen pressure may also contribute to a reduced mitochondrial respiration with a consecutive increase in lactate production. Hypoxia was also demonstrated to decrease adiponectin expression in adipocytes [71]. The physiologic basis of adipose tissue hypoxia may be related to a reduction in adipose tissue blood flow and capillary density which has been reported in both obese humans and animals. The secretory profile of both pre-adipocytes and adipocytes includes a variety of chemoattractants for immune cells. Such accumulation of immune cells and inflammation of adipose tissue has been shown in obese humans [73] and appears to be more pronounced in omental than subcutaneous adipose tissue [74], which would also fit with the concept that the amount of visceral fat is the culprit for the metabolic and cardiovascular complications of obesity. Obesity and oxidative stress A study from Japan demonstrated that fat accumulation is associated with systemic oxidative stress in humans and mice [67]. It has long been known from early clinical studies that 235 Part 3 Pathogenesis of Diabetes Overnutrition Macophage Paracrine and autocrine inflammatory signals Endocrine inflammatory signals Fat insulin resistance Liver insulin resistance Systemic insulin resistance Muscle insulin resistance Figure 14. Intra-abdominal fat cells exhibit a differing expression profile and are lipolytically more active than subcutaneous adipocytes. Moreover, they show a greater accumulation of lymphocytes and macrophages, indicating greater proinflammatory activity. Visceral adipose tissue also has a much higher blood vessel and nerve density leading to a much greater metabolic activity. Visceral adipose tissue drains into the portal vein and thus the liver is directly exposed to fatty acids and proteins released from this active fat depot promoting insulin resistance in the liver. Thus, the inflammatory process is detected, not only at the level of adipose tissue, but may also affect the liver and possibly other organs. As enlarged visceral fat depots are frequently associated with fat accumulation in the liver, it was also hypothesized that secretory products from the visceral adipose tissue may directly cause hepatic insulin resistance. In summary, a variety of data suggests that chronic overnutrition with a high-fat, high-sugar diet and as a consequence an accumulation of body fat is the primary cause of chronic inflam236 mation in obesity and may promote the development of systemic insulin resistance which affects many tissue including liver, muscle and the brain (Figure 14. It should not be neglected that apart from an unhealthy diet, other lifestyle factors such as lack of physical activity may substantially contribute to these pathologic processes. In addition, weight reduction facilitates reaching the primary treatment goal of a metabolic control close to normal. Interestingly, almost all disturbances mentioned above are potentially reversi- Obesity and Diabetes Chapter 14 ble by weight loss. By contrast, adiponectin levels are known to rise in relation to weight reduction. In a recent study in surgically treated morbidly obese subjects a significant reduction in macrophage infiltration was documented in adipose tissue samples after a mean weight loss of 22 kg within 3 months [70]. More importantly, recent studies using a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet were at least equally effective. In a recent meta-analysis of such studies, HbA1c, fasting glucose and some lipid fractions improved with lower carbohydrate content diets [85]. In a study from Israel, a Mediterranean type of weight loss diet showed small advantages in comparison to the classic low-fat, low-carbohydrate diet in a subgroup of overweight participants with diabetes [86]. The message from this and other studies [87,88] is that the macronutrient composition of the diet is secondary for weight reduction. In patients with nephropathy, however, protein intake remains a critical issue and should be limited in accordance with current recommendations [89]. It should be stressed that all efforts for dietary changes should be made as simple as possible for patients as they may also be burdened by many requirements to manage their diabetes. Therefore, in patients without insulin, three meals a day may be more appropriate and advantageous to reach the individual dietary and weight goals. This option may be particularly valuable for patients with poor metabolic control. There is also evidence that the pattern of adipokines and macrophage-associated gene expression can change dramatically under such conditions [91]. This approach, however, can only be applied for a limited period of time and requires intensive medical surveillance. Another possibility is to change the pattern of nutrient intake to modify adipose tissue inflammation. To date, there is little practical information available to indicate whether specific effects of single components in the diet can ameliorate adipose tissue inflammation independent of calorie restriction. There is no doubt that more research is urgently required to explore the potential of dietary components and to develop novel strategies that may help to provide better dietary solutions for the management of obesity. Another reason is that subjects with diabetes focus more on blood glucose control which could result in neglecting other health problems. Finally, the effect of various antidiabetic agents to increase weight or prevent weight loss has to be considered [79]. Dietary approaches the cornerstones of a weight reduction program for obese patients with diabetes include a moderately hypocaloric diet, an increase in physical activity and behavior modification, very similar to the recommendations for obese subjects without diabetes. The most important single measure is the reduction in fat intake, particularly in saturated fatty acids. As shown recently, a diet rich in fiber and complex carbohydrates has some beneficial effects on measures of glucose and lipid metabolism but these effects may be small and possibly of limited clinical importance [83]. In addition, sulfonylureas are known to promote weight gain because of their action to promote insulin secretion. There is growing evidence, however, that weight gain under glitazone treatment occurs mainly in subcutaneous depots, not in the visceral depot, which should have less deleterious metabolic consequences. Furthermore, weight gain under administration of glitazones is not only caused by an increase in fat mass, but also by enhanced fluid retention. In contrast, metformin and -glucosidase inhibitors have a modest weight lowering potential [79]. As sibutramine is known to activate the sympathetic nervous system, this drug should not be used in patients with diabetes and poorly controlled hypertension or coronary artery disease. In this group of patients surgery is by far the most effective treatment mode with excellent long-term results compared to all other methods. In the Swedish Obese Subjects study, a large prospective trial comparing bariatric surgery with conventional dietary treatment, sustained weight loss 20 kg was achieved in the surgically treated subjects with practically no significant weight change in the control group. Weight loss and diabetes resolution was greatest in patients undergoing combined restrictive and malabsorptive surgical methods [100]. The majority of insulin-treated patients can stop insulin treatment within a few months after surgery and all other medications for diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors can be considerably reduced or discontinued. There are also many studies indicating how rapidly most circulating adipokines are normalized in relation to the degree of weight loss in these patients. Weight lowering drugs Another component in the treatment of obesity is the adjunct administration of weight lowering drugs. As the efficacy of currently approved drugs is limited, drug treatment is only recommended if the non-pharmacologic treatment program is not sufficiently successful and if the benefit: risk ratio justifies drug administration [97]. Orlistat is a gastric and pancreatic lipase inhibitor that impairs the intestinal absorption of ingested fat. Sibutramine is a selective serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor that enhances satiety and slightly increases thermogenesis. It is apparent that an excess of body fat promotes insulin resistance and impairs insulin secretion. In parallel, most if not all underlying disturbances benefit from weight loss or dietary interventions. As conventional concepts combining an energy-reduced diet and an increase in physical activity frequently have poor long-term results, however, more effective weight loss strategies should be developed and evaluated. Body-mass index and causespecific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Evidence for a strong genetic influence on childhood obesity despite the force of the obesogenic environment. Human obesity: a heritable neurobehavioral disorder that is highly sensitive to environmental conditions. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a genetically programmed failure of the beta cell to compensate for insulin resistance. Excessive obesity in offspring of Pima Indian women with diabetes during pregnancy. Gestational weight gain and risk of overweight in the offspring at age 7 y in a multicenter, multiethnic cohort study. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. The influence of food portion size and energy density on energy intake: implications for weight maintenance. Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor- in human obesity and insulin resistance. The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue: regulation by obesity, weight loss and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. Expression pattern of tumour necrosis factor receptors in subcutaneous and omental human adipose tissue: role of obesity and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Impairment of insulin signaling in human skeletal muscle by coculture with human adipocytes. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 is a potential player in the negative crosstalk between adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Autocrine action of adiponectin on human fat cells prevents the release of insulin resistance inducing factors. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. Saturated fatty acids, but not unsaturated fatty acids, induce the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mediated through Toll-like receptor 4. Loss-of-function mutation in Tolllike receptor 4 prevents diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Endoplasmatic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Reduction of macrophage infiltration and chemoattractant gene expression in white adipose tissue of morbidly obese subjects after surgery-induced weight loss. Hypoxia is a potential risk factor for chronic inflammation and adiponectin reduction in adipose tissue of ob/ob and dietary obese mice. T-lymphocyte infiltration in visceral adipose tissue: a primary event in adipose tissue inflammation and the development of obesity-mediated insulin resistance. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural localization of leptin and leptin receptor in human white adipose tissue and differentiating human adipose cells in primary culture. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout and uric calculous disease. Impact of obesity on metabolism in men and women: importance of regional adipose tissue distribution. Management of the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes through lifestyle modification. Beneficial effects of high fiber intake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Comparison of a high-carbohydrate diet with high-monounsaturated-fat diet in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

The sympathetic activation produced by these drugs antagonizes the action of insulin and cocaine use has been identified as an independent risk factor for diabetic ketoacidosis [103] anxiety symptoms hot flashes discount 75 mg tofranil mastercard. The risk of diabetic ketoacidosis may be increased by the omission of insulin before discos and parties to avoid the potential risk and embarrassment of hypoglycemia anxiety symptoms of menopause purchase tofranil 50mg with visa. Ecstasy is also associated with severe hyponatremia anxiety symptoms heavy arms tofranil 25mg with mastercard, secondary to inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone anxiety symptoms in toddlers buy 25 mg tofranil otc, which may complicate the management of diabetic ketoacidosis [95] anxiety lyrics buy tofranil 75mg mastercard. Cannabis Cannabis is not known to affect glucose metabolism but its effects on the central nervous system may increase appetite and impair recognition of hypoglycemia anxiety journal prompts generic 75mg tofranil. Use of cannabis in low doses is associated with sympathetic activation and tachycardia; at high doses, parasympathetic activation may predominate, resulting in bradycardia and hypotension. In the absence of any structural heart disease, these effects are usually well tolerated. Intravenous drug abuse Recreational drug use often disrupts normal lifestyle and a person with diabetes may abandon the daily routine of regular meals and insulin injections. Recreational drug use may also be only one aspect of a chaotic lifestyle associated with other high-risk behaviors. This can result from the use of any recreational drug, but intravenous drug abuse (particularly of opiates, but also amfetamines) is particular damaging and is strongly associated with poor social support, criminality and mental illness. Intravenous drug use is uncommon in people with diabetes (as it is in the Hypoglycemia While the association between recreational drug use and diabetic ketoacidosis is well established, there are few data suggesting any association with hypoglycemia. Such drugs, however, are often taken in conjunction with alcohol and may be associated with poor oral intake of carbohydrate both of which will increase the risk of hypoglycemia. Moreover, amfetamine-like stimulants can induce frenetic behavior at night clubs and raves which can induce hypoglycemia in people treated with insulin [104]. Furthermore, the sympathomimetic effects of cocaine and amfetamine-type stimulants may mimic the autonomic signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia. Advice on recreational drug use in diabetes Illicit drugs cause significant morbidity and are hazardous for people with diabetes. When exposed to recreational drugs and alcohol, modest reductions in insulin dosage and regular consumption of carbohydratebased snacks or non-alcoholic sugary drinks are required, particularly if strenuous dancing is to be undertaken. Travel Diabetes must not be regarded as a bar to short or long-distance travel, although careful planning may be required to avoid metabolic disturbances and other problems of diabetes that could have particularly serious consequences away from home. Diet and an adequate fluid intake may be disrupted while traveling or staying abroad, and local differences in climate, food, endemic diseases and medical facilities may compromise diabetes control. Blood glucose levels should be monitored frequently during travel and holidays, and people with diabetes must be able to take a pragmatic approach to deal with contingencies. Occasionally, specific diabetic complications or other medical disorders such as uncontrolled hypertension or ischemic heart disease can jeopardize health and safety during travel and periods away from home. Insurance and medical care abroad Comprehensive medical insurance is essential to cover accidents and illness that require medical assistance, and loss of medical equipment and drugs. The insurance policy must cover diabetes and other pre-existing medical conditions, as claims relating to these may otherwise be rejected. Most travel policies contain exclusions, which frequently include diabetes; a person with diabetes may not be covered for conditions such as a stroke or myocardial infarction for which diabetes is a recognized risk factor. When appropriate, insurance must be adequate to cover any dangerous sporting activities (when hypoglycemia could be particularly hazardous), and the costs of emergency air transport home in the event of a serious accident or illness. A list of insurers who do not load premiums against people with diabetes can be obtained from national diabetes associations. Irrespective of medical insurance cover, it should be appreciated that emergency medical care available in some countries is suboptimal or even potentially dangerous for a diabetes-related emergency. In some parts of the world, insulin is not readily obtainable and intravenous fluids are in short supply. These considerations may influence the choice of holiday destination for people with diabetes. Drugs and equipment Essential items for the diabetic traveller are listed in Table 24. Occasionally, a severe reaction to a vaccine may cause a temporary rise in insulin requirements. Air travelers treated with insulin should carry an ample supply in their hand luggage. Preferably, another supply of medication should be carried by a relative or friend in case of loss or theft. When traveling by air, medication and blood monitoring equipment should not be consigned to the hold, because of the risk of losing luggage. During travel, insulin can be carried in an insulated cool bag or a pre-cooled vacuum flask. These should also allay the suspicions of airline security, immigration and customs officials who discover syringes and drugs in luggage. If a prolonged stay abroad is intended, it is useful to carry a prescription letter listing all medications (with generic names, as brand names often vary between countries), insulin-injection devices and blood-testing items. Allowance may have to be made for delayed flights or long intervals between meals, while fatigue or travel sickness may blunt appetite. Alcohol Drinking alcohol before and during air travel is best avoided because of the risk of hypoglycemia; also, the diuretic effects of alcohol favor dehydration, which has been implicated in deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism during long-haul flights (although diabetes does not appear to confer greater risk) [107]. Blood glucose Blood glucose levels should be monitored frequently while in transit and when changing time zones. It is often safer to allow in-flight blood glucose values to be slightly higher than usual to avoid the risk of hypoglycemia. Insulin treatment There is no evidence-based information on how to adjust insulin dosages during flights that cross several time zones, and this probably accounts for the variability in the advice that is given [108]. Each case should be discussed individually with the patient, taking into account the duration of the flight and the change in time zone, the usual insulin preparations and dosages, the size and timing of meals, and the results of glucose monitoring. If this injection is delayed by more than 12 hours, then additional insulin with food will be needed in the interim. Extremes of temperature and high altitude can disable some blood glucose meters and affect the accuracy of blood glucose test strips, although the cabin pressure of passenger aircraft (equivalent to an altitude of up to 8000 feet) should not pose problems [105]. While on holiday, it is sensible to carry a spare meter and/or visually read glucose strips in case the meter fails. Those prone to motion sickness should take an anti-emetic to prevent nausea and vomiting from disrupting glycemic control. Antidiarrhoeal agents and a broad-spectrum antibiotic should be carried, particularly if traveling to regions with a high risk of acquiring gastroenteritis. People with peripheral sensory neuropathy should take comfortable and appropriate footwear for travel and for holiday use, as foot ulceration may be caused by wearing ill-fitting sandals or walking barefoot across rocks or even hot sand. Long flights and crossing time zones these pose several potential problems, ranging from the timing and composition of airline meals to ensuring that insulin dosages will cover the flight and adjust to local time on arrival. Meals Times of serving in-flight meals after take-off can usually be obtained from the airline. Meals can either be regarded as snacks or as main meals, depending on the travel schedule. Oral antidiabetic agents Additional doses are not usually required to cover an extended day. Subcutaneous insulin absorption can be accelerated by high ambient temperatures, such as in a sauna (see Chapter 27), and this effect has variable clinical significance in very hot climates. Modern formulations are quite stable, but sometimes denature if exposed to high temperatures and shaken; in this case, discolored particles or a granular appearance (distinct from the normal cloudiness of delayed-action preparations) may be seen injected every 4 hours or so on the basis of blood glucose measurements. Sometimes, there are no visible changes, but the insulin appears to lose its effect, with the usual dosages failing to lower blood glucose. Particularly in hot countries, insulin is best stored in a refrigerator; if one is not available, insulin can be protected by a damp flannel or a porous clay pot containing some water or wet sand, placed in a cool part of the room. Food and drink When traveling abroad, it is essential to know the basic form of carbohydrate that is eaten locally, and useful to learn to judge quantities of foods such as pasta or rice. Items selected from local menus can be supplemented with bread, biscuits or fruit. Sugarfree drinks are difficult to obtain in many countries but bottled water is safe and usually available. Quick-acting carbohydrate to treat hypoglycemia should always be carried and stored appropriately: dextrose tablets may disintegrate or set hard in hot and humid climates unless wrapped in silver foil or stored in a suitable container, while the temperature-dependence of chocolate is well known. Cartons of fruit juice cannot be reused once opened; a plastic bottle with a screw top is preferable. Social isolation may exist until new friends are made and access to alcohol and recreational drugs may increase, with the attendant risks that have been highlighted. Sexual activity may commence or increase, introducing issues of sexual health and pregnancy, and novel forms of exercise may be more readily available. Barriers to diabetes control include fear of hypoglycemia, diet, irregular schedules, lack of parental involvement, limited finances, recreational drugs and alcohol. There is a natural desire for students with diabetes not to appear different from their peers and this may lead them to assign a lower priority to diabetes management than they would normally and to undertake potentially high risk activities. Diabetes services need to be responsive to the needs of adolescents and young adults who are leaving home. Such individuals are often poorly informed about the inherent risks associated with, for example, alcohol and drugs [95,116] and these and other needs may not be addressed in the context of a routine diabetes consultation [115]. Before the individual leaves home, a formal re-education program should be offered in which alcohol, drugs, exercise, sex and sick-day management are discussed [117]. Individuals leaving home need to think about their mealtimes; it can be difficult for someone living alone to motivate themselves to prepare substantial meals and many adolescents have limited cooking skills. Regular meals are provided in university halls of residence, but the nature and content of the food, particularly the carbohydrate content, may not be ideal. Students should be advised to monitor blood glucose levels frequently during examination periods. Both acute hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia Intercurrent illness Any intercurrent infection should be treated promptly and appropriately, with adequate replacement of fluids and carbohydrate in the form of drinks if possible. Recreational activities the impact of physical exercise and sport on diabetes is discussed in Chapter 23. Patients need advice about strenuous and unaccustomed exercise during holidays, such as beach sports or prolonged and vigorous dancing. Leaving home As a child with diabetes grows up, inevitably parental input to the day-to-day management of diabetes is reduced with increasing autonomy of the adolescent. In teenage years this is often manifest by a deterioration in glycemic control (Chapter 52). Even in 394 Social Aspects of Diabetes Chapter 24 impair cognitive function and can cause mood changes and may affect examination performance adversely. Therefore, students should try to optimise glucose control during examinations and ensure that a supply of rapid-acting carbohydrate is available during an examination. Many students may prefer to remain under the care of their "home" diabetes team, but it is important that they know how to contact local specialist diabetes services in the university town for advice or assistance. Medical practitioners in university health services have a duty to ensure that students with diabetes are offered regular diabetes follow-up. The student should be encouraged to confide at an early stage with a reliable friend or colleague about their diabetes and the potential problems that may arise [117]. This may cause embarrassment talking to recent acquaintances about having diabetes. University authorities have a pastoral responsibility for students with diabetes [111]. Effect of acute hypoglycemia on visual information processing in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Adverse events and their association with treatment regimens in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Frequency and morbidity of severe hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated diabetic patients. Hypoglycaemia and driving in people with insulin-treated diabetes: adherence to recommendations for avoidance. Visual field loss with capillary non-perfusion in preproliferative and early proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Driving standard visual fields in diabetic patients after panretinal photocoagulation. Global regulations on diabetics treated with insulin and their operation of commercial motor vehicles. Diabetes and driving: desired data, research methods and their pitfalls, current knowledge, and future research. Frequency, severity and morbidity of hypoglycemia occurring in the workplace in people with insulin-treated diabetes. Employment and diabetes: a survey of the prevalence of diabetic workers known by occupation physicians, and the restrictions placed on diabetic workers in employment. Educational achievements, employment and social class of insulin dependent diabetics: a survey of a young adult clinic in Liverpool. Education and employment experiences in young adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Generic 50 mg tofranil mastercard. Firework Music for Dogs with Noise Anxiety! Reduce Bonfire night Stress!.

References