|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Colleen Koch, MD, MS, MBA

The German co-determination and works council system was also examined in the light of suggestions that it might act as a possible European model gastritis diet alcohol order phenazopyridine 200 mg on line. An evaluation of co-determination was then undertaken gastritis diet ű??űżŽšżťŪ buy phenazopyridine 200mg overnight delivery, followed by an exploration of the European works council issue in the context of the European Union gastritis cystica profunda best phenazopyridine 200mg. They have therefore decided to produce a small company newsletter for this purpose gastritis reddit buy phenazopyridine 200mg low price. There is a relatively small but active number of union members within the company on most of the sites gastritis reviews discount 200 mg phenazopyridine visa. Decide upon the policies and practices for the newsletter to ensure that it is a genuine communication sample gastritis diet 200mg phenazopyridine with visa, reflective of the organisation as a whole. Questions 1 How is the concept of empowerment different from that of employee involvement and industrial democracy? In your answer, give examples from both micro and macro levels in the organisation. Write a report recommending the policies in terms of aims, objectives and implementation that should be considered in its foundation. Ask one group of people to devise reasons why there should be greater participation by employees in the workplace, and ask the other group to put the case against extending participation. Each group should evaluate their reasons from the viewpoint of employers, managers and employees. Then ask the whole group to debate the question of employee participation from each side,–Ē—Ąs viewpoint. Case study 1 Total quality management Precision Tool Engineering is a company producing machinery and machine tools and some other related engineering products for specialist production companies. It employs a total workforce of 400, two-thirds of whom work in the production departments. In late 1993 the company,–Ē—Ąs management decided to introduce a total quality management scheme to increase efficiency and quality control. In 1990 more flexible arrangements had been introduced, accompanied by a breakdown of old work demarcation lines. Machines were now built by flexible teams of workers employing different skills. Workers were asked to inspect the quality of their work, with the result that the need for specialist inspectors was greatly reduced, and both time and money were saved. Agreements were negotiated with the union for extra pay as a result of the increase in worker responsibility. Problem-solving groups were formed based on work groups with voluntary participation. Group leaders, who were mainly supervisors, were trained in how to run a group and in prob- Case study 2 577 Case study 1 continued lem-solving techniques. The aims of the groups were to:,—É–ł,—É–ł,—É–ł,—É–ł identify problems inside their work area; propose solutions; identify problems outside their work area; refer external problems to a review team. Some of the areas they identified were that team leaders had felt uncomfortable in their role, and there had been considerable scepticism from some groups of workers. The review team was made up mainly of managers with one representative from each group, usually the group leader. The unions were lukewarm towards the scheme, and some shop stewards were directly against it. Since undertaking his empowerment initiatives the company has increased in size 11 times and, in the first half of the 1990s, became one of the fastest-growing companies in Latin America. According to Semler (1993),–Ē—āDemocracy is the cornerstone of the Semco system,–Ē—Ą (p. All employees, excluding management, elect representatives to serve on these committees. Bureaucracy has been drastically cut by reducing 12 layers of management down to three. There are only four titles in the company: Counsellors, who are similar to vice-presidents and coordinate general policy and strategy; Partners, who run the business units; Coordinators, senior managers in charge of sales, marketing, production and assembly area foremen; and Associates, who are the rest of Semco employees. Semco also practises what it calls,–Ē—āreverse evaluation,–Ē—Ą, which includes what is now generally known as 360-degree appraisal. This is done anonymously by multiple choice questionnaire, and the grades are publicly displayed. Before anyone is hired or promoted they must be evaluated by all the people who will work with them. Work is organised in manufacturing cells, with work teams that are given responsibility to create a whole product. This avoids assemblyline-production boredom and alienation, and increases employee control over their work process. Semco has reduced barriers between departments and encourages,–Ē—āmanagement by wandering around,–Ē—Ą. Management does not decide unilaterally what profit is to be shared; that decision is made after negotiations with the workforce. Semler also allows the workforce to ,–Ē—āself-set pay,–Ē—Ą,–Ē–ľ a policy whereby employees decide their own salaries. This is done through negotiations with the unions, comparing local pay rates and consulting with both management and the team. Individuals can also choose how much of their earnings can be basic pay and how much bonus. Employees can also choose when they work, flexitime is encouraged and time punch clocks have been removed. There is a high union presence, and Semco encourages union membership as well as carrying out negotiation and discussion with the unions. There are disagreements, and some have led to strikes, but the strikes are far less than under the old regime. The ultimate aim is,–Ē—ātransparency,–Ē—Ą: all information within and about the company is available to all employees. Workers are even given training by trade union officials on the company premises and in the company time on issues such as understanding the company balance sheets, to enable more effective participation. The ethics of employee empowerment,–Ē—Ą, paper presented at References and further reading the Conference of Ethical Issues in Contemporary Human Resource Management, Imperial College, London, 3 April. Price Waterhouse Cranfield Project on International Strategic Human Resource Management (1990) Report. Price Waterhouse Cranfield Project on International Strategic Human Resource Management (1991) Report. A review of the development and performance of employee involvement,–Ē—Ą, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. Over the last 100 years the organisation has built a reputation for quality foods, and so depends on relatively discerning shoppers for its market; most of its outlets are in the South-West and South-East of Britain. The organisation is a large employer (more than 4000 employees); it is highly dependent upon part-time, female labour and casual student workers for shopfloor employees, with full-time management staff consigned to given stores. The firm does experience costly medium-to-high labour turnover, largely because of the unsocial hours to which all employees are rostered, and the transient nature of student labour. Wage rates are average for the sector, and were unaffected by the Minimum Wage Regulation. The organisation has never recognised trade unions, but has had a fairly informal system of local employee representation committees, many of which have fallen into disuse in recent years. British farmers have also been active in publicly denouncing the profiteering that has been evident in the retail food sector. Consequently, the big firms are engaged in,–Ē—āprice wars,–Ē—Ą and are actively increasing the quality and variety of goods on offer while also focusing on the level of sevice offered within their stores. Malone Superbuy is not in the top league, but nevertheless has been affected by increasing competition in the sector. To remain competitive in the market the firm must:,—É–ł,—É–ł improve the quality of service offered to customers throughout the organisation; find ways of cutting labour costs. Further to developing a strategy for change to deal with market pressures, the firm must also decide whether it intends to:,—É–ł,—É–ł accept a trade union presence and attempt to build a partnership agreement; adopt a substitution or suppressionist approach to union recognition. The Managing Director has already decided that he wants a comprehensive report to indicate how the firm will move forward and this will be presented under the title,–Ē—āSuperbuy Shapes Up For the Future! This term describes the proliferation of world trade, foreign direct investment, worldwide mergers and acquisitions and a burgeoning of telecommunications, faster and cheaper transport and rapid technological change. Globalisation has also been considerably enhanced by the integration of markets both worldwide and at regional level, as well as witnessing the rise of new and potentially powerful markets in China and Central and Eastern Europe. The trend towards privatisation and deregulation has led to an increase in cross-border integration in areas such as telecommunications, energy and finance. As companies and organisations expand their crossborder activities there has been a concomitant increase in business activity together with an increase in cross-border integration of their production and services. This in turn has created an increasing interest in the processes by which international management coordination and control can be exercised. As Hyman (1999) states: After two decades in which the superior performance of such,–Ē—āinstitutionalised economies,–Ē—Ą as Germany and Japan was widely recognised, the conventional wisdom of the 1990s has been that dense social regulation involves rigidities requiring a shift to market liberalism. Globalisation has taken place against a backcloth of social and political turbulence in the twentieth century, and has continued in the wake of the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and the resulting economic and political problems. There has been a huge and continuing growth of the world,–Ē—Ąs population, which has intensified the problems of 586 Introduction to Part 5 poverty for many poor nations. Pollution has brought green issues to the forefront of the consciousness of political and business policy-makers. We have witnessed a challenge to Western economic supremacy with the rapid growth of the Asia Pacific states, led by the,–Ē—ātigers,–Ē—Ą,–Ē–ľ Japan, China, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong,–Ē–ľ as well as Singapore and Malaysia. This updates developments in the European Union in regard to approaches to harmonisation as reflected in social policy in the wake of the Amsterdam Treaty (1997) and the Lisbon Conference (2000). The last chapter examines trends in the Asia Pacific rim, especially in Japan, China and the other,–Ē—ātiger,–Ē—Ą economies. Multinational corporations and the geography of international production,–Ē—Ą, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. To demonstrate what is institutionally distinctive and particular about one type of business system and demonstrate how economic and political strategies and those of firms are embedded within a national institutional framework. To consider the limitations of current work in the field and future directions for research. The primary analytical focus is the institutional environment,–Ē–ľ namely the legal and regulatory frameworks, industrial relations traditions and employment systems,–Ē–ľ in terms of its impact on organisations. This perspective zooms in on the institutional influences that constrain or enable organisational action. The focus here is on organisational strategy and structure and its interaction with market competition. Organisations are assumed to have a high degree of strategic choice enabling them to find the best way of organising their resources for competitive advantage, in other words achieving a,–Ē—āfit,–Ē—Ą between the organisation,–Ē—Ąs strategy-structure and its external business environment. While environmental constraint is recognised, its influence tends to be under-emphasised and under-explored. The ways in which this competitive context is affected by, for example, cooperative institutional links or collective tradition and the implications for strategic choice go largely unrecognised. International organisations and the business markets they operate in are notoriously complex and dynamic. Conducting research in the field is often expensive and methodologically difficult (Adler, 1984; Brewster et al. While the majority of these states are broadly capitalist,–Ē–ľ they are based on a system of production that emphasises the market as the main mechanism for exchange, consumption and distribution,–Ē–ľ each has followed a distinctive and unique pathway to industrial capitalism. The economic, political and social characteristics of individual market economies are shaped by and embedded within a social system that provides them with distinctively national characters. These national characteristics impact on and inform the manner by which business systems operate. Other economies, for example the German and Japanese economies, followed different paths that emphasised either high-quality system production or the production of standardised products that were continuously improved through the use of quality programmes. These national patterns are likely directly to influence patterns of human resource management and industrial relations; this point is further developed in subsequent parts of this chapter. The economic and political strategies of state actors and those who represent the interests of capital and finance and organised labour are embedded within a social system of class relations, institutional regulation and culture that characterises their national qualities. The institutional characteristics of national business systems impact on firms in terms of their corporate strategies, both domestically and in terms of internationalisation. Equally, the role and make-up of financial capital will have some impact on corporate strategies, as will the industrial relations system. So, institutional analysis suggests that economic, political and social processes and structures particular to one business system are embedded within a national institutional framework. It follows from this that national patterns of industrial organisation in and between the state, industrial and finance capital and labour are embedded within enduring institutional frameworks. These frameworks of national regulation,–Ē–ľ markets, nonmarket institutions or some combination of the two,–Ē–ľ enable and constrain corporate strategies, the strategies of organised labour and those of the national state. Therefore capital, labour and the state within a particular business system operate within a web of relationships characterised by significant differences in terms of the presence or absence of social institutions that regulate activities beyond the confines of market institutions. To summarise, empirically and historically, national business systems represent distinctive patterns of economic organisation. While these contributions cover much common ground, they provide subtle variations in the description, evaluation and conceptualisation of business systems and the institutional depth and embeddedness of national patterns of regulation. Lane,–Ē–ľ national industrial orders Lane (1995) examines patterns of stability and change in the British, French and German business systems. Her approach follows the theoretical specification outlined above to argue that national patterns of industrial organisation are embedded in society, but distinguishes between economic and social embeddedness in the creation of national industrial orders.

This may work where employees can be encouraged to swap a percentage of their base pay for this variable element but many organisations introduced these schemes as additional to existing compensation levels (see Kellaway gastritis flare up diet purchase 200mg phenazopyridine free shipping, 1993) gastritis diet ÝūŚÍ buy phenazopyridine 200mg overnight delivery. Current research looking at these schemes indicates two main findings: gastritis symptoms lump in throat discount 200 mg phenazopyridine otc,—É–ł gastritis quick cure discount phenazopyridine 200 mg,—É–ł They have some positive impact on performance gastritis diet coke purchase phenazopyridine 200mg visa. This has been achieved by the introduction of schemes which are based on modern job evaluation and grading schemes within which the compensation increases the variable element rather than the base as in the past gastritis symptoms vomiting purchase phenazopyridine 200mg without a prescription. In this world-view competency can be defined as an underlying characteristic of an individual which is causally related to effective or superior performance in a job. This differs from traditional,–Ē—āpay-by-skill,–Ē—Ą in that it is applied across the organisation to all workers (rather than just the traditional skills) and the required,–Ē—ācompetencies,–Ē—Ą are somewhat broader than the definition of,–Ē—āskill(s),–Ē—Ą. This breadth of definition allows the application and adaptation of traditional job evaluation schemes by taking into account current changes in the organisation of work and the utilisation of new technology. Thus job evaluation techniques were rescued from decline by becoming more flexible, broader in coverage and applicable to modern multi-skilled workers (Pritchard and Murlis, 1992). Whichever system is applied, a main advantage lies in the versatility available for organisations to set their own,–Ē—ācharacteristic set of knowledge, skills, abilities and motivations,–Ē—Ą. In recent debates much of the attention has turned to discussion of a contract which is unwritten and yet seen as being equal in relation to influence as any written terms and conditions. The psychological contract is seen to underpin all reward and performance management systems in that it conceptualises the wage/effort bargain for a new generation of workers and owners. In the following section we consider the formation of the contract and identify the,–Ē—āagreed,–Ē—Ą terms (if such they can be called) forming the basis from which human resource managers seek to develop performance norms, organisational values and note the psychological contract as a mechanism in the continuing strategy to encourage,–Ē—āmen [sic] to take work seriously when they know that it is a joke,–Ē—Ą (Anthony, 1977: 5). The psychological contract,—Ā Defining the psychological contract As with many aspects of human resource management,–Ē–ľ such as motivation and performance,–Ē–ľ the psychological contract is somewhat elusive and challenging to define (for a discussion of this, see Guest, 1998a). However, it is generally accepted that it is con- 520 Chapter 13 ¬¨ Reward and performance management cerned with an individual,–Ē—Ąs subjective beliefs, shaped by the organisation, regarding the terms of an exchange relationship between the individual employee and the organisation (Rousseau, 1995). As it is subjective, unwritten and often not discussed or negotiated, it goes beyond any formal contract of employment. The psychological contract is promise based, and over time assumes the form of a mental schema or model, which like most schema is relatively stable and durable. A major feature of psychological contracts is the concept of mutuality,–Ē–ľ that there is a common and agreed understanding of promises and obligations the respective parties have made to each other about work, pay, loyalty, commitment, flexibility, security and career advancement. They researched the perceived obligations of two parties to the psychological contract by identifying the critical incidents of 184 employees and 184 managers representing the organisation. From the results they inferred seven categories of employee obligation and twelve categories of organisation obligation. In relation to employee obligations they make reference to both concrete and abstract inputs the organisation hopes/expects the employee will bring to the organisation. At the first level these involve an expectation that the employee will work the hours contracted and consistently do a good job in terms of quality and quantity. The organisation will desire that their employees deal honestly with clients and with the organisation and remain loyal by staying with the organisation, guarding its reputation and putting its interests first, including treating the property which belongs to the organisation in a careful way. Employees will be expected to dress and behave correctly with customers and colleagues and show commitment to the organisation by being willing to go beyond their own job description, especially in emergency. It is possible to suggest that many of these expectations reflect the common law terms implied in the contract of employment and as such it is the,–Ē—āmanifestation,–Ē—Ą of the required behaviours more than the existence of a psychological contract which is used to manage,–Ē—ānorms,–Ē—Ą within the organisation. On the other side of the contract we can note the obligations placed on the organisation in terms of the expectations each employee has of the deal. Most employees would want the organisation to provide adequate induction and training and then ensure fairness of selection, appraisal, promotion and redundancy procedures. While recent legislation has centred on the notion of work,–Ē–ľlife balance, it is argued that an element of this agreement is an employee expectation that the organisation will allow time off to meet personal and family needs irrespective of legal requirements. It has long been held that workers ought to have the right to participate in the making of the decisions which affect their working lives (see Adams, 1986; Bean, 1994; Freeman and Rogers, 1999); the debate relating to the psychological contract suggests that employees further expect organisations to consult and communicate on the matters which affect them. With the increasingly high levels of,–Ē—āknowledge,–Ē—Ą workers it is accepted that organisations ought to engage in a policy of minimum interference with employees in terms of how they do their job and to recognise or reward for special contribution or long service. Organisations are generally depended upon to act in a personally and socially responsible and supportive way towards employees, which includes the provision of a safe and congenial work environment. We have already noted that in relation to reward and performance management systems there is a need to act with fairness and consistency; the expectation goes further in that the application of rules and disciplinary procedures must be seen to be equitable. This perceived justice should extend to market values and be consistently awarded across the organisation, indicating the link therefore to a consistency in the administration of the benefit systems. The final element that many workers expect their employer to provide is security in terms of the organisation trying hard to provide what job security is feasible within the current economic climate. The psychological contract 521 Stop and think 1 Write down your expectations of your employer and what you consider to be their expectations of you. Previous decades have seen many organisations forced, by increased competition and the globalisation of business, to seek to remain competitive by cutting costs and increasing efficiency. The restructuring has also given rise to redundancies, has had the significant impact of reducing job security of those who remained, has removed many of the middle-level management grades and consequently reduced possible promotion opportunities for all employees. While long-term job security, promotion and career progression were perceived by many employees, whose psychological contract was possibly formed many years earlier, to be the,–Ē—ākey,–Ē—Ą obligations which were owed by the organisation in return for their loyalty and commitment, modern organisations (and in some respects the,–Ē—āmodern,–Ē—Ą employee) are learning to live without such elements in the psychological agreement. The consequences have been predictable; employees feel angry at the apparent unilateral breaking of the psychological contract and at the same time insecure, having lost trust in the organisation. Commitment is reduced, with motivation, morale and performance being adversely affected. This is potentially dangerous for the organisation, as lean organisations need effort and commitment in order to get work done and at the same time a willingness to take risks in the pursuit of innovation. It is suggested (Rousseau, 2001; Guest and Conway, 2002) that negative change in the employment relationship may adversely affect the state of the psychological contract. Sparrow (1996) claims that the psychological contract underpins the work relationship and provides a basis for capturing complex organisational phenomena by acting in a similar manner to that of Herzberg,–Ē—Ąs hygiene factors. Good psychological contracts may not always result in superior performance, or indeed in satisfied employees; but poor psychological contracts tend to act as demotivators, which can be reflected in lower levels of employee commitment, higher levels of absenteeism and turnover, and reduced performance. Herriott and Pemberton (1995: 58) suggest that the captains of industry have set in motion a revolution in the nature of the employment relationship, the like of which they never imagined. For they have shattered the old psychological contract and failed to negotiate a new one. It has long been accepted that two forms of psychological contract, termed relational and transactional, operate in the employment relationship (Table 13. The former refers to ,–Ē—āa long term relationship based on trust and mutual respect. The employee offers loyalty, conformity to requirements, commitment to their employer,–Ē—Ąs goals and 522 Chapter 13 ¬¨ Reward and performance management Table 13. In return, the organisation supposedly offered security of employment, promotion prospects, training and development and some flexibility about the demands made on the employees if they were in difficulty. However, as a result of the changes outlined above, it is suggested that some employers have had difficulty in maintaining their side of the bargain. As a result, the old relational contracts have been violated and have been replaced by new, more transactional contracts, which are imposed rather than negotiated and based on a short-term economic exchange. In return the employer offers (to some) high pay, rewards for high performance and simply a job,–Ē—Ą (1998: 388). Stop and think If the psychological contract is changing as current research appears to suggest, what are the organisational implications for managing the psychological contract in the future? The psychological contract needs careful management; although it is unwritten it remains a highly influential aspect of the employment relationship. In flatter, delayered organisations with limited opportunities for career progression and the absence of any guarantee of a job for life, attaining and maintaining employee commitment becomes increasingly more challenging for management. To manage the psychological contract in the future, organisations need to offer,–Ē—ārealistic job previews,–Ē—Ą to new entrants, recognise the impact of change on those remaining and,–Ē—āinvest in the survivors,–Ē—Ą, change the management style to push towards cross-functional teamwork, design tasks and structures to allow employees to feel a sense of accomplishment and develop their skills to increase their own,–Ē—āemployability security,–Ē—Ą, create a new kind of commitment through the creation of meaning and values between employees, not just from a top-down mission statement, be attentive to the need to balance work and other aspects of life and be continuous in communication with employees. Guzzo and Noonan (1994) take the perspective that psychological contracts can have both transactional and relational elements. Employers may have to demonstrate to employees that they can keep to a sound and fair transactional deal before attempting to develop a relational contract based on trust and commitment. The essential point is to recognise that all psychological contracts are different. It is important for the organisation to appreciate the complexities of transactional and relational contracts and to recognise that psychological contracts will have elements of all dimensions and that contracts are individual, subjective and dynamic. The significance of the psychological contract in relation to performance management is that it highlights how easy it is for organisations to assume that employees seek primarily monetary rewards; this is not necessarily the case. From the dawn of the industrial era managers have sought to control the effort side of the agreement by utilising their power to determine the wage. Performance management (or more accurately forms of performance-related pay) has formed a key activity for managers and management in the quest to increase the benefits gained by the application of labour power. The choice of which management system to adopt has been driven by the answer proposed to the basic question,–Ē—āwhat motivates workers to perform at higher levels? We can see the development of reward management along the lines suggested by Etzioni (1975) in terms of coercive (work harder or lose your job), remunerative (worker harder and receive more money) and normative (worker harder to achieve organisational goals). Current trends in the management of worker performance fall to be considered in the area of normative managerial practices, but are fraught with difficulty in an era where emotional labour and the knowledge worker hold such a central place in organisational success. These developments need to be considered alongside the evolution of an ambiguous employment relationship (the breakdown of the psychological contract) and the rise of insecurity within modern organisations (reflected in the growth of,–Ē—ābutterfly workers,–Ē—Ą). The notions of,–Ē—āproductivity through our people,–Ē—Ą, customer focus, strong(er) leadership, flatter structures and cohesive cultures all suggest a management framework which seeks to improve individual and organisational performance in ways that can be measured, a concentration on competence (inputs) alongside attention to attainment (outcomes). These elements turn attention to the fact that in modern organisations it is the quality and behaviours of the employees that generate, as much as other inputs, competitive 524 Chapter 13 ¬¨ Reward and performance management Figure 13. However, a set of key questions still remain:,–Ē—āwhat motivates workers to perform at higher levels? These, as our discussion of the psychological contract suggested, leave us with some confusion and inconsistencies which present management with as many questions as answers. The recent developments in this area involve two themes:,—É–ł,—É–ł the performance management process, and contingency pay. As Lowry (2002) argues, the management of employee performance is usually seen as a necessary function of the managerial cadre. Centrally, it links a number of themes, including the extent to which the organisation has identified strategic goals reflecting the needs of the business and the degree to which these are communicated to and shared by each employee. We can further note that general definitions suggest that performance management involves a formal and systematic review of the progress towards achieving these goals. The cycle consists of five elements which provide a framework within which we can audit the delivery of strategic objectives with a view to developing continuous improvement. These elements are presented as a common link between organisational and individual performance which underlies the development of a committed, motivated, loyal workforce. In simple terms, it is suggested that the cycle indicates a system within which performance objectives are set, outcomes are then measured, results are fed back, rewards are linked to outcomes and changes are made before new objectives are set for which the outcomes can be measured. Where the purpose of setting such objectives is to direct, monitor, motivate and audit individual performance they must fulfil both of these criteria, otherwise the process will result in the opposite effects being secured. The application of expectancy and goal-setting theories implies that this is best achieved where the individual has an important role in the determination of the objectives for the period concerned. As suggested in the discussion above, this will encourage the selection of appropriate goals which are specific, attainable and owned by the individual. The process, as a management tool, is established on the basis that organisational objectives can be broken down and translated into individual goals, the attainment of which can then be effectively measured. However, not all of us are,–Ē—āsales,–Ē—Ą representatives or,–Ē—āwidget,–Ē—Ą-makers; indeed, in the current economic climate such crude measures may be inappropriate and in some respects a return to ,–Ē—āold pay,–Ē—Ą notions of piecework. The growth of,–Ē—āknowledge,–Ē—Ą workers has been accompanied by a change to competence-based approaches to measurement which centre on the three stages of competence development (knowwhat, know-why and know-how; see Raub, 2001). Therefore the outcomes can be measured in relation to the individual,–Ē—Ąs success in deploying, integrating and improving their competence in the identified field of activity. This allows the organisation to refocus on the development of competitive advantage through the application of,–Ē—ācore knowledge,–Ē—Ą, including tangible and intangible assets. It allows the application of,–Ē—ājust enough discipline,–Ē—Ą to establish a relevant,–Ē—ācore knowledge,–Ē—Ą base which is defined by strategic business drivers and monitored to maintain balance (see Klien, 1998). The purpose of performance planning, review and appraisal needs to be made clear if employees at all levels in the organisation are to play an active part in the process. It is possible that some employees and line managers may meet performance appraisal schemes with distrust, suspicion and fear, but an integrated and effective process can lead to increased organisational performance and employee motivation. It is important for employees to be genuinely involved in the design of an appraisal scheme, the evaluation of performance, and the objective-setting process. An appraisal scheme should be set up in an atmosphere of openness, with agreement between management, employees and employee representatives on the design of the scheme (Grayson, 1984: 177). Employees need to have a clear understanding of the purpose of the process (evaluative or developmental). It needs to provide direction for continuous improvement activities and identify both tendencies and progress in performance. Manifestly it needs to facilitate the understanding of cause and effect relationships regarding performance while remaining intelligible to those employees to which it applies. It ought to be dynamic, covering all of the company,–Ē—Ąs business processes, and provide real-time information about all aspects of performance. A scheme that does not include employees,–Ē—Ą attitudes is unlikely to allow performance to be compared against benchmarks because it will not be composed of effective performance measures. Finally, we can note that a performance appraisal system should provide a perspective of past, present and future performance which is visible to both employees and management. The most commonly used measures will therefore relate to the individual,–Ē—Ąs attitude to work as well as the quality of their work and their attendance and time keeping. These will be assessed alongside their knowledge of the job and productivity, while more subjective measures involving a judgement of their ability to interact with others will be included in a good scheme in order to develop an insight into the effectiveness of recruitment procedures. In terms of,–Ē—ārating,–Ē—Ą or,–Ē—āscoring,–Ē—Ą individual employees, a number of,–Ē—ātarget areas,–Ē—Ą can be identified for assessment. The employees,–Ē—Ą actual output in terms of measurable productivity, timeliness and quality may be directly assessed as part of the appraisal scheme. This presupposes the employees,–Ē—Ą job role is open to such quantitative assessment. Andrew White, company representative, stated,–Ē—āWe found that the previous scheme was appraising managers on competences beyond their current job role, which in some cases led to demotivation,–Ē—Ą (White, November 2002).

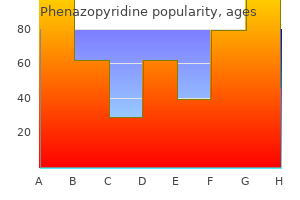

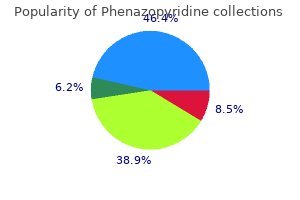

The entrepreneurship credit is the effective contribution of each course of a potential entrepreneurship profile gastritis fundus buy phenazopyridine 200mg with mastercard. The distance between each attribute is assumed equal intervals and therefore the quantitative measures assigned to the qualitative attributes will be used in parametric tests gastritis diet Áůūűŗť discount phenazopyridine 200mg visa. For each student the Entrepreneurship score is computed only on the mapped courses as: Entrepreneurship Score (1-4 scale) = Entrepreneurship credit (1-5 scale) x Course Grade (1-4 scale) Credit (1 to 3 percourse) 2013 on around 1800 courses for 7000 students per semester with a response rate of 50% and in summer 2013 on around 900 courses for 3400 students gastritis gerd symptoms 200 mg phenazopyridine otc. Total Entrepreneurship credit (3/ 5) Step 1: Mapping entrepreneurship values As hypothesis of the Method of Equal-Appearing Intervals the concept of entrepreneurship is reasonably thought of as one-dimensional gastritis symptoms natural remedies cheap 200 mg phenazopyridine fast delivery. The next step is to have judges (Instructors and entrepreneurs) rate each statement on a 1-to11 scale in terms of how much each value statement indicates a value embedded in entrepreneurship gastritis diet 8 hour purchase phenazopyridine 200 mg line. According to Part 1 chronic gastritis histology 200 mg phenazopyridine mastercard, the component learning outcomes of entrepreneurship are cultural specific. By selecting the judges in our community the methodology ensure that the mapping includes cultural specificity. The number of judges was not enough to split the results between faculty members and entrepreneurs. The composition of an "entrepreneurship" value given by the judges under the constraint of the current available measures virtues are shown in the below table in the column weight. The contribution of each course is averaged over three semesters to define Entrepreneurship credit. Step 3: Calculate an entrepreneurship score Sample Size for the cohort and Course mapping the data used is the undergraduate cohorts from 1999 to 2009 (around 13600 students), the sub selection of the departments of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Computer Science, Management and Marketing, Mass Communication, Mathematics and Statistics, Nursing and Health Sciences, Sciences, Social and Behavioral Sciences) covers around 8000 students. On the selected departments we could map 87% of the courses (496,000 Credit over 570,000 credit). The below graph shows the percentage of the course that we could map with the existing courses: from 60% for the courses in 1997 up to 100% for the current courses. We have selected the Departments of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Computer Science, Management and Marketing, Mass Communication, Mathematics and Statistics, Nursing and Health Sciences, Sciences, Social and Behavioral Sciences with an acceptable coverage from 1999 until now. Calculating an entrepreneurship score the Entrepreneurship score along cohorts for the Undergraduate programs of specific Departments is presented on a 1-4 scale. A down trend means that the program composition evolves toward an instruction with less learning outcomes embedded in an entrepreneurship value and respectively an up-trend toward courses with higher learning outcomes embedded in an entrepreneurship value. Sciences and Nursing & Health sciences programs have the better entrepreneurship scores, and Social and behavioral Sciences, Computer Sciences and Management & Marketing have the lower scores. Assuming different cohorts results are comparable means underestimating effects of changes in students and faculty populations, student course-taking patterns. First we assume the comparability of the instruction even the number of instructors has tripled following the growth of the University between 1995 and 2012. Second we assume that the courses are comparable since 1997, even the curriculum has evolved during the last 6 years. In further work we expect to ratify the model with the measures of the Exit Survey (graduating senior survey), the alumni database and the alumni survey. The back test can be done by comparing the number of entrepreneurs and the Program with higher potential entrepreneurs. Some research perspectives on entrepreneurship education, enterprise education and education for small business management: a ten-year literature review. Harmeling S, Sarasvathy S and Freeman R, (2009) Related Debates in Ethics and Entrepreneurship: Values, Opportunities, and Contingency, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. Promoting entrepreneurial mindsets at universities: a case study in the South of Spain. Guidelines for Planning and Implementing Quality Enhancement Efforts of Program and Student Learning Outcomes. Saquing Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila, Philippines Abstract Poverty is a common problem that developing countries are faced with. Often rooting from unemployment, such concern is seen to be addressed by taking action with an entrepreneurial mind-set, to be able to survive in an uncertain economic situation. Given that the business school is one of the most influential institutions to aspiring businessmen, this paper aimed to compare business schools in two developing countries, in terms of their most dominant philosophies in molding future entrepreneurs. Data were taken from interviews with administrators of educational institutions offering business courses in Indonesia and the Philippines. The findings posit that the business schools in both countries play a significant role in addressing economic challenges by producing the kind of entrepreneurs each school will have out of their philosophies. A report on the impact of business schools in the United Kingdom carried out for the Association of Business Schools by the Nottingham Economics Centre at Nottingham Business School, looked at the role of business schools as a focal point for teaching, research and consultancy. Business schools were found to be at the forefront of promoting entrepreneurship and were focal points of university and industry engagement. Head of Nottingham Economics and report author, Dr Andy Cooke, said: "Since the 1960s, business schools have continued to push forward their role in the economy as providers of enhanced business education. Nowadays, they are catalysts for entrepreneurship, provide focal points for discussion, research and consultancy activity, they contribute knowledge to private and public sector forums and organisations as well as enhancing the reputation and economic wellbeing of their universities. It is often said that to become a successful entrepreneur, young people do not need to go to college. Some entrepreneurship mentors even suggest that going to college is a waste of time. They encourage college or university students to quit their school and start to build their own business immediately. Velasco (2013) found that entrepreneurship education in the Philippines is heavily focused on the development of entrepreneurs in terms of I. It is directly related to more business, more job opportunities and better quality of life. Most economists today concur that entrepreneurship is a necessary element for stirring economic growth and job opportunities in all societies. Many developing countries have come to the realization that entrepreneurship serves as the engine for economic growth and have consequently started to formulate series of policies to stimulate entrepreneurship development. He stated: "Business schools alone certainly cannot prevent an economic crisis, but they are uniquely positioned to help the leaders of tomorrow prepare to manage risk and adhere to ethical business practices, both of which are essential safeguarding the global economy. However, there is lack of focus in developing creativity and innovation as a mindset of the student in the formal education system. There is also minimal support from the academe and industry to aid nascent entrepreneurial undertaking to grow and sustain the business. With entrepreneurship education being a work in progress in both countries, and considering that business schools indeed play a role in contributing to national economic situations, it is worthwhile to look into the philosophies guiding these institutions in educating their students. According to McGraw-Hill Higher Education (2003), "Behind every school and every teacher is a set of related beliefs ¬≠ a philosophy of education ¬≠ that influences what and how students are taught. What are the most dominant philosophies of the administrators of the following institutions? Universitas Sebelas Maret Fakultas Ekonomi What are the institutional philosophies of the participating institutions? The College of Management and Entrepreneurship of Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila is a dynamic, needsdriven college committed to the development of outstanding practitioners in the fields of entrepreneurship, finance, management, marketing and public administration. With a passion for responding to the complex needs of society and enhancing change in the system, the College has established a wide network, particularly for its Bachelor of Science in Public Administration program, reaching out to help hundreds of undergraduates employed in local government offices and agencies. Its Bachelor in Business Administration program has expanded to include majors in entrepreneurship, financial, treasury management, marketing, and management. Sebelas Maret University Fakultas Ekonomi is one of the best faculties in one of the best universities in Indonesia. It is comprised of 40 statements, to which the participants responded on a scale from 1, "Strongly Disagree," to 5, "Strongly Agree. The most dominant philosophies of education of the participants were taken from their numerical answers to the questionnaire, which were tallied and summarized according to the eight educational theories. The institutional philosophies of the participating schools were taken from publicized vision, mission and objectives. As a result of the depth interviews, supplementary comments of the participating administrators helped clarify and elucidate the data taken from the institutional philosophies. Research Design the research methodology of this study relied mainly on qualitative research, tending to be exploratory, flexible and gaining insights to provide a better understanding of a situation. In particular, a literature search was conducted by studying the published reports and researches in relation to entrepreneurship education. Relevant to business research projects, this popular method of exploratory research involves a desk study of available information in libraries, online resources, commercial data bases, and so on. Consequently, the researchers conducted depth interviews, where questions came from a relevant questionnaire adopted from the Oregon State University ¬≠ College of Education. Depth interviews are used to tap the knowledge and experience of those with information relevant to the problem or opportunity at hand. A Summary of the Philosophy and Education Continuum Chart of Oregon State University - School of Education Modernity Traditional and Conservative Authoritarian (convergent) General or World Theories Related Educational Philosophies Related Theories of Learning Idealism Realism Post Modernity Contemporary and Liberal Non-Authoritarian (divergent) Pragmatism Existentialism Reconstruction- Perennialism Essentialism Progressivism ism/ Critical theory Information Behaviorism Cognitivism/ Constructiv- Humanism Processing ism be analogous a computer. Behaviorism Behaviorists believe that behavior is the result of external forces that cause humans to behave in predictable ways, rather than from free will. Observable behavior rather than internal thought processes is the focus; learning is manifested by a change in behavior. Cognitivism/Constructivism the learner actively constructs his or her own understandings of reality through acting upon and reflecting on experiences in the world. Humanism Humanist educators consider learning from the perspective of the human potential for growth, becoming the best one can be. The shift is to the study of affective as well as cognitive dimensions of learning. What are the most dominant philosophies of the administrators of the participating institutions? It presents theories from modernity to post modernity, from traditional and conservative to contemporary and liberal, and from authoritarian (convergent) to nonauthoritarian (divergent). It shows the connection among related educational philosophies, related theories of learning, coming from the general or world philosophies. Further, Cohen utilizes a questionnaire on Educational Philosophies Self-Assessment whose scoring guide summarizes the following educational philosophies and psychological orientations: Perennialism the acquisition of knowledge about the great ideas of western culture, including understanding reality, truth, value, and beauty, is the aim of education. Essentialism Essentialists believe that there is a core of basic knowledge and skills that needs to be transmitted to students in a systematic, disciplined way. Progressivism Progressivists believe that education should focus on the child rather than the subject matter. Reconstructionism/Critical Theory Social reconstructionists advocate that schools should take the lead to reconstruct society in order to create a better world. Schools have more than a responsibility to transmit knowledge, they have the mission to transform society as well. Information Processing For information processing theorists, the focus is on how the mind of the individual works. For progressivists, based on the Philosophy and Education Continuum Chart, ideas should be tested by active experimentation, and learning should be rooted in questions of learners in interaction with others. In terms of psychological orientation, on the other hand, the administrators differ. In information processing, moreover, the mind makes meaning through symbol-processing structures of a fixed body of knowledge. This orientation describes how information is received, processed, stored, and retrieved from the mind. Implementing excellent teaching and education in management that demands academic staff development and students self-reliance in obtaining knowledge, skill, attitude and the norms of living together in society; conducting scientific and applied research in management and business, and also disseminating research discovery; and organizing community services to support the implementation and development of management science that oriented to the society empowerment. Generate graduates with strong character, having managerial competence and highly competitive on national and international level; generate qualified scientific and applied research, and to disseminate research discovery on national and international level; and generate innovative community service that benefits the society. Mission Guided by this vision, we commit ourselves to provide quality education to the less privileged but deserving students and develop competent, productive, morally upright professionals, effective transformational leaders and socially responsible citizens. What aspects of their most dominant philosophies do the participating institutions share? As earlier mentioned, both participating institutions adhere to the philosophy of progressivism, focusing on the individuality, the learner `experiencing the world. The learner is a problem solver and thinker who makes meaning through his or her individual experience in the physical and cultural context. On the other hand, the teacher plays as "Gardner tendering the child, assuming a high degree of authority while respecting the personality of the child. With the implementation of this tenet/aspect of the educational philosophy, progressivism, being employed by the participating institutions, the students are geared towards developing entrepreneurial mindset, skills, behavior and attitudes which in turn enable them to be more creative and confident in their career venture. An entrepreneurship education is required for all students that will not only provide theoretical knowledge but will also guarantee to develop among graduates an entrepreneurial mindset, armoring them with the beneficial key competencies. This can only be achieved through student-centered teaching and learning that employs innovative, experiential learning methodologies in conjunction with assessment mechanisms that award credit for extra-curricular and practical activities delivered by a coordinated, student-focused institutional infrastructure. This study explored the most dominant philosophies of two participating institutions. The examination of the educational philosophy of an institution is important because it is useful in guiding, critiquing and justifying teaching methodologies that help in shaping their graduates as potential stakeholders of the business world. Based on the findings of this study, the use of experience-based teaching methods is critical to developing entrepreneurial skills and abilities among graduates. It is imperative that the educator impart to the learner a realworld or simulated experience in order to allow the students to have a grasp of operating their own business. It is therefore essential that educators are recognized and encouraged to act as "entrepreneurial proponents" and provided with the means to enhance their own teaching skills and to be entrepreneurial and innovative in developing new teaching methods and resources. In considering the value of the educational philosophy, it is apparently helpful to the participating institutions, or any institution, for that matter, to consider the benefits of it offers to the particular field of education they put premium into. Further, it serves as a framework to justify educational practices and an avenue to develop evaluative and critical thinking to improve the quality of education. Enterpreneurship Education in Ireland: Towards Creating the Entreprenerial Graduate, 2009. Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila, "College of Management and Entrepreneurship Homepage. Even though business people areconsidered to have logical mindset and accustomed to analyze empirical economy data, theyhardly distinguishmyth from proven entrepreneurship theories.

Establishing targets There is a strong body of research which supports the theory that the setting of goals leads to the overall performance improvement of the employees concerned diet during gastritis order phenazopyridine 200 mg without a prescription. Moreover gastritis diet for gastritis cheap 200 mg phenazopyridine otc, realistic gastritis ulcer diet phenazopyridine 200 mg generic, hard gastritis diet ŗůÍūÓ order 200 mg phenazopyridine amex, specific goals produce better performance than easy goals or no goals at all gastritis diet ÁýÍÚý buy cheap phenazopyridine 200mg. They direct the attention of the employee to what needs to be Chapter 8 Performance management 297 achieved gastritis diet ýŤÚÓ‚ŤšŪŗˇ order phenazopyridine 200 mg with mastercard, they mobilise the effort put in by the employee, they increase the persistence of the employee in their desire to reach the goal and get them to think carefully about the right strategies they need to employ to achieve the targets. Under this system, the organisational targets were cascaded down the hierarchy so each manager had a set of targets to achieve. For a period of a few years, this method of management was seen as a panacea to the ills of British industry, but the system failed to produce the expected success. This was due to a number of external factors, specifically the appalling industrial relations of that period and the two oil crises of that decade which made any form of target setting extremely challenging. This acronym helps to set out the key features of a successful set of targets: ¬≠ Firstly, they should be specific and stretching. To set stretching targets supports further aspects of Goal theory, which states that motivation and performance are higher when goals are difficult but accepted, support is given to achieve them and feedback is regular and valued. If employees disagree with the targets because they find them too difficult to achieve, then they may well set out to prove this by determining to fail. The external environment is constantly changing and the targets need to be adjusted to meet those changes. This is not to say that changes should be made each week or month but there can be no sacrosanct 298 An introduction to human resource management Chapter 8 target that will last for years. If an individual has a large number of targets, say 25 or 30, then the process of monitoring and measuring these targets would be insuperably complex. Many organisations reach a compromise and provide for employees to have a minimum and maximum number of specific targets ¬≠ usually from around 4¬≠10. Sales employees will have a schedule, which will set out the target volume of sales and the ideal breakdown between products. Accounts employees will have a target of invoices to be issued or payments to be processed. In contracting, for example, if projects are late, then penalties are often incurred. Employees responsible for some part of a major project will themselves have very important deadlines as a target because, if they are late, then it can have a severe knock-on effect upon other parts of the project. At the time of writing, the many contractors involved in the new Wembley Stadium all have very clear time targets throughout their organisations as the fate of many sporting events rests on whether they meet their deadlines or not. The credit control department may have a target to reduce average payment time to a certain level (say, 20 days) within 6 months. The design team may have a target to produce a new product design within 6 months. An engineering department may have a target of a new factory layout designed, planned and implemented to be ready for operation at the end of the summer factory closure. Chapter 8 Performance management Target 1 Ensure that a minimum of 79% of all visitors who come to register a birth or death or to give notice of intention to marry are seen within 30 minutes of arrival Ensure that all responses to written requests for certificates and other information are despatched within 24 hours Ensure that 95% of telephone calls are answered within five rings 299 Figure 8. Within each sector, specific measurable objectives are defined with outcome communicated within the organisation on a regular basis. Linking the performance management scheme to the Balanced Scorecard is seen as essential to ensure each employee understands how their actions and achievements gell into the total organisational picture. Competence-based systems the competency movement has gathered strength in recent years, chiefly as a reaction to what is seen as the rigid, quantifiable, dataobsessed objectives methods. Encouraging the employee to adopt the behaviours required by the organisation and following the behaviours exhibited by high performers in the post are seen as a more coherent and broader approach to achieving improved employee performance. Works with the customer to develop the business relationship Sets customer expectations at a high but achievable level. Win-win situations sought between self and customer Seen by customer as a partner Always listens to the customer and suggests improvements to their wants An ambassador 4 Seeks to anticipate customer Asks customers for feedback Sought by requirements. Performs in line with reputation and image 2 Performs own job without proper regard for customer opinion. Needs constant reminding about customer skills Limited awareness of customer needs or the effect of own actions. Adds no value to the relationship Co-operation Responsiveness Customer relationships 1 Identifying customer needs Figure 8. The competencies, and the preferred behaviour that measures them, need to be drawn up. They developed a framework centred around their set of values, namely: the Customer comes first Total commitment to quality Teamwork makes a winning team Development of employee empowerment and responsibility Communication is open and honest. In the late 1990s, the Bank of Scotland had a framework made up of the following: Personal competencies, which are generic to the organisation (in other words, every employee needs to have them). There are 11 of these and they include commitment, adaptability, problem solving and breadth of view. There are 26 of these and they include security, health and safety, financial administration, committee secretaryship and technical support to customers. There are 20 of these and they include branch cash handling/telling, personal lending/risk management support, term deposit administration and securities administration. Many organisations will incorporate two or more such meetings into their scheme as a year is seen to be too distant a time for discussion on such an important subject. In terms of objectivity, it would appear that the target-setting approach wins hands-down. Targets are agreed and there should be a clear system of how they can be measured so there should be no argument or need to make judgements. Either the materials were sourced Chapter 8 Performance management 303 by the purchasing department and in place in the factory on time or they were late. Here are a few situations that can cast cloud over the objectivity accolade: Moving the goalposts. The annual target for sales (part of the overall company business plan) is set in the light of a poor economic situation where sales are difficult to come by. As a sales representative, you work hard and, 6 months into the year, you are ahead of budget. As pay is partly determined by whether you are ahead of the target, you are feeling confident and pleased. The Board then announce a revised business plan on the basis that the economic situation is picking up. From a position of being ahead of target, you are now only just up to the new target. The Board will argue that, if they do not increase the target, they will fall behind their competitors or give more pay to the sales force than they deserve in the light of the economic circumstances. One of your major targets is to produce a revised working plan for the warehouse, which will involve increasing the number of shifts and introducing annual hours. After 3 months, you have worked hard and spent a lot of time on this project, with a revised system in draft form. The company then decide to sell the warehouse as part of a general re-structuring. You run the credit control department and you are jointly charged with a systems analyst to introduce a new computerised system. Halfway through the period, the systems analyst leaves the company and a new one is assigned to the project. He has different views on a number of points (some of which are quite sensible) but these are not resolved in time to meet the deadline. There are other criticisms of a system based solely on objectives/targets: Are the objectives evenly matched? This may not occur too often in large departments, such as sales, where targets are similar (even so, difficulties can occur here). However, when employees all have different jobs, such as in an administrative setting, it is almost impossible to 304 An introduction to human resource management Chapter 8 ensure that the objectives are of equal difficulty. The outcome is that some average employees with these soft objectives are considered high performers by the outcome of the scheme and, contrary-wise, some top performers come out with only average performance. The individual may be tempted to put all their efforts into achieving their own objectives and treat the rest of their work as less important. After all, if they are to be measured on those specific objectives, this is a strong temptation. The outcome is that their work becomes unbalanced, important routine work can be neglected and unexpected problems may not be tackled with the required enthusiasm. An individual employee, focused on their objectives, will also be tempted to neglect other members of the team or other teams in the organisation. This can have a severe effect upon both the short-term achievements, which can only happen when employees work together as a team (getting a contract completed on time, getting an complex order despatched to a customer) and upon the long-term culture of the organisation where team-working may be a required value. If you use the measure of clear-up rates, then you run the risk of repeating the scandal in one force in the mid-1990s who were found to have colluded with burglars to get them to admit to very high number of burglaries that they did not commit (in return for lower charges and sentences) so that the clear-up rate improved greatly. Chapter 8 Performance management 305 (Incidentally, it was only when the number of identical burglaries continued and the real villains were apprehended by the police force in the next county that the fiddle came to light! Given these difficulties, should we not concentrate our energy on an effective competency framework? Rating problems Even when systems are in place to assist managers to rate on a consistent basis (such as set out in Figure 8. Managers may rate employees on the basis of their personal relationships rather than by an objective measure of their competencies and abilities. Friendships may be regarded as too important to be spoilt by the harsh realities of a poor rating. Even without personal prejudice, a good majority of managers do find it difficult to give their employees a bad rating. Having to face employees at an appraisal interview and justify their criticisms can be an experience that managers do not want to go through. It is much easier to simply give an average rating on the scale and hope the employee will improve anyway. This problem can also lead to rating drift, where managers are happy to raise the rating of their employees but never reduce the ratings, even when it is justified. When coming to a decision on a rating on an annual appraisal, a manager may be too influenced by an event that happened a few days or weeks ago that are fresh in their minds. Let us take the example of an employee whose performance with customers had been far from satisfactory for most of the year. In the month before the appraisal, there 306 An introduction to human resource management Chapter 8 was a major achievement resulting in a letter of thanks from a customer. A manager may regard the way they act and their methods of working to be the best practice. It is all too easy for employees who take a different approach to be rated lower, despite evidence that the differing methods work just as well. Is performance all about achievement of goals or can behaviour itself be regarded as a type of performance. An American psychologist, Campbell, for example, considered that: `Performance is. The administrator may be have a very high rating with customer relations in that she builds up a rapport with the customer, treats them with respect and understanding and has good listening skills amongst other measures. But her job is to collect the overdue debt and, if her competence is too customer oriented, there runs the risk that the debt will not be paid. There are also numerous examples of athletes who are extremely competent at their chosen expertise at a world-class performance level but who never manage to produce the results on the international stage. Variations on rating systems As the rating element of performance management is the most difficult area to get right, a number of variations have been produced to try to ensure that the system is fair, robust and more sophisticated. Chapter 8 Performance management Points Behavioural patterns Consistently seeks to help others Tolerant and supportive of colleagues Contributes ideas and takes full part in group meetings Listens to colleagues Willing to change own plans to fit in Keeps colleagues in the picture about own activities Mixes willingly enough 307 50 max 40 30 20 10 0 Figure 8. Firstly, examples of behaviour reflecting effective and ineffective job performance are obtained from people who are held to be expert about the job to be rated, which is then checked by a second group on the relevance of the behavioural examples within the dimension chosen (in this example, teamwork is the dimension). If the experts place the behaviour at different points on the scale, then this example is usually deleted because a high level of clarity and consensus is required. The advantage of the scheme is that the ratings are anchored against carefully agreed observed behavioural patterns. Getting experts to agree upon the scale can be difficult, given the ultimately subjective nature of behaviour. It is no surprise, then to find that organisations are deciding to incorporate both sets of measurement in their performance management framework. Individuals have their job description or profile, which sets out their day-to-day responsibilities and accountabilities; they will also agree certain objectives for the period in question and they will also be measured against the competencies that apply to their job as part of the competence framework. On the other hand, it can lead to a performance management system that is complicated and difficult to grasp, especially for new employees. Stage 3: Providing feedback the third stage in the performance management process is to provide effective feedback to employees. There are two parts related to this process: firstly, deciding on what basis the feedback should be based and, secondly, how it should be carried out. In recent years, however, 360 degree appraisal has become increasingly popular where feedback is produced by a number of sources, including colleagues, subordinates, internal and external customers and then fed back to the employee. Traditional appraisal interview Moderating process Most organisation, although delegating the rating process to the line managers, will build in a system of moderation whereby the results are considered as a whole by the next level of management. A major drawback for many schemes is that these forms are sometimes lengthy and complicated; it is not unknown for some long-established schemes to have as many as 10 pages to be completed. Although they are designed to be comprehensive and give support to the process, the parties concerned, especially the managers who may have to complete them for up to 20 employees, often baulk at having to fill them in.