|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Theresa B. Young, PhD

The Treasury may womens health yarmouth me discount fertomid 50mg on line, by directions given to a subsidiary of the Assembly Commission women's health tipsy basil lemonade discount fertomid 50 mg mastercard, require the subsidiary to include in any accounts which the subsidiary prepares (under womens health 60 plus buy cheap fertomid 50 mg online, for example womens health haverhill generic 50mg fertomid otc, the law relating to companies or charities) such additional information as may be specified in the directions women's health center lagrange ga discount 50 mg fertomid amex. The inclusion of information in any accounts in compliance with such directions does not constitute a breach of any provision which prohibits pregnancy timeline cheap 50mg fertomid otc, or does not authorise, the inclusion in the accounts of that information. The Auditor General may carry out examinations into the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which the Assembly Commission has used its resources in discharging its functions. Subsection (1) does not entitle the Auditor General to question the merits of the policy objectives of the Assembly Commission. The Auditor General may lay before the Assembly a report of the results of any examination carried out under this section. This section applies in respect of a financial year for which the Treasury make arrangements with the Welsh Ministers under section 10(8) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (c. The Welsh Ministers must prepare a set of accounts for the group of bodies which provide information to the Welsh Ministers in accordance with the arrangements under section 10(8). Accounts prepared under this section may include information referring wholly or partly to activities which- a. The accounts must contain such information in such form as the Treasury may direct. The Treasury must exercise the power under subsection (4) with a view to ensuring that the accounts- a. For the purposes of subsection (5)(a) and (b) the Treasury must in particular- a. Any accounts which the Welsh Ministers are required to prepare under this section for any financial year must be submitted by the Welsh Ministers to the Auditor General no later than 30th November in the following financial year. But the Welsh Ministers may by order substitute another date for the date for the time being specified in subsection (7). No order may be made under subsection (7) unless the Welsh Ministers have consulted- a. A statutory instrument containing an order under subsection (7) is subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of the Assembly. The Auditor General must examine accounts submitted under section 141 with a view to being satisfied that they present a true and fair view. Where the Auditor General has conducted an examination of accounts under subsection (1), the Auditor General must- a. A person who acts as auditor for the purposes of section 10(2)(c) or (8)(c) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (c. The Audit Committee may consider, and lay before the Assembly a report on, any accounts, statement of accounts or report laid before the Assembly by- a. The Assembly must publish a document to which this subsection applies as soon after the document is laid before the Assembly as is reasonably practicable. Welsh public records are not public records for the purposes of the Public Records Act 1958 (c. But that Act has effect in relation to Welsh public records (as if they were public records for the purpose of that Act) until an order under section 147 imposes a duty to preserve them on the Welsh Ministers (or a member of the staff of the Welsh Assembly Government). Subsection (2) applies to Welsh public records whether or not, apart from subsection (1), they would be public records for the purposes of the Public Records Act 1958. An order under this section may (in particular) make in relation to Welsh public records provision analogous to that made by the Public Records Act 1958 (c. An order under this section which imposes on the Welsh Ministers (or a member of the staff of the Welsh Assembly Government) a duty to preserve Welsh public records, or Welsh public records of a particular description, must include provision for the Lord Chancellor to make such arrangements as appear appropriate for the transfer of Welsh public records, or Welsh public records of that description, which are in- a. No order is to be made under this section unless the Lord Chancellor has consulted the Welsh Ministers. No order under this section which contains provisions in the form of amendments or repeals of enactments contained in an Act is to be made unless a draft of the statutory instrument containing it has been laid before, and approved by a resolution of, each House of Parliament. An order under subsection (1)(f) may be made in relation to a description of records- a. A statutory instrument containing an order under subsection (1)(f) is subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament. Resolution of devolution issues For provision about the resolution of devolution issues see Schedule 9. The Secretary of State may by order make such provision as the Secretary of State considers appropriate in consequence of- a. An order under this section may not make provision with respect to matters within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament. A statutory instrument containing an order under this section is (unless a draft of the statutory instrument has been approved by a resolution of each House of Parliament) subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament. Her Majesty may by Order in Council make such provision as Her Majesty considers appropriate in consequence of- a. No recommendation is to be made to Her Majesty in Council to make an Order in Council under this section which contains provisions in the form of amendments or repeals of enactments contained in an Act unless a draft of the statutory instrument containing the Order in Council has been laid before, and approved by a resolution of, each House of Parliament. A statutory instrument containing an Order in Council under this section is (unless a draft of the statutory instrument has been approved by a resolution of each House of Parliament) subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament. This section applies where it appears to the Secretary of State that the exercise of a relevant function (or the failure to exercise a relevant function) in any particular case might have a serious adverse impact on- a. The Secretary of State may intervene under this paragraph in that case, so that- a. An intervention by the Secretary of State under this section in relation to a function is to be made by giving notice to the person or persons on whom it is conferred or imposed. Where an intervention has been made under this section in a case, the Secretary of State must, in addition to the notice under subsection (4), give notice to- a. In determining whether to make an order under this section, the court or tribunal must (among other things) have regard to the extent to which persons who are not parties to the proceedings would otherwise be adversely affected by the decision. Where a court or tribunal is considering whether to make an order under this section, it must order notice (or intimation) of that fact to be given to the persons specified in subsection (5) (unless a party to the proceedings). A person to whom notice (or intimation) is given in pursuance of subsection (4) may take part as a party in the proceedings, so far as they relate to the making of the order. Any power to make provision for regulating the procedure before any court or tribunal includes power to make provision for the purposes of this section including, in particular, provision for determining the manner in which and the time within which any notice (or intimation) is to be given. The provision is to be read as narrowly as is required for it to be within competence or within the powers, if such a reading is possible, and is to have effect accordingly. Her Majesty may by Order in Council specify functions which are to be treated for such purposes of this Act as may be specified in the Order in Council- a. A statutory instrument containing an Order in Council under this section is subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament. The Welsh Ministers may by order provide in respect of any Welsh word or phrase that, when it appears in the Welsh text of any Assembly Measure or Act of the Assembly, or any subordinate legislation made under an Assembly Measure or Act of the Assembly or by the Welsh Ministers, it is to be taken as having the same meaning as the English word or phrase specified in relation to it in the order. An Assembly Measure or Act of the Assembly, or any subordinate legislation made under an Assembly Measure or Act of the Assembly or by the Welsh Ministers, is to be construed in accordance with any order under subsection (2); but this is subject to anything to the contrary contained in the Assembly Measure, Act of the Assembly or subordinate legislation. This section applies in relation to subordinate legislation made by the First Minister or the Counsel General as in relation to subordinate legislation made by the Welsh Ministers. Any power of a Minister of the Crown or the Welsh Ministers under this Act to make an order is exercisable by statutory instrument. Any power conferred by this Act to give a direction includes power to vary or revoke the direction. In sections 95(3), 109(2) and 151(2) "enactment" includes an Act of the Scottish Parliament and an instrument made under such an Act. The Secretary of State may by order determine, or make provision for determining, for the purposes of the definitions of "Wales" and the "Welsh zone", any boundary between waters which are to be treated as parts of the sea adjacent to Wales, or sea within British fishery limits adjacent to Wales, and those which are not. An Order in Council under section 58 may include any provision that may be included in an order under subsection (3). No order is to be made under subsection (3) unless a draft of the statutory instrument containing it has been laid before, and approved by a resolution of, each House of Parliament. No order containing provision under subsection (2)(a) is to be made unless a draft of the statutory instrument containing it has been laid before, and approved by a resolution of, each House of Parliament. Subject as follows, this Act comes into force immediately after the ordinary election under section 3 of the Government of Wales Act 1998 (c. Subject to subsections (2), (3) and (6), the following provisions come into force immediately after the end of the initial period- a. The Secretary of State may by order make any other transitional, transitory or saving provision which may appear appropriate in consequence of, or otherwise in connection with, this Act. An order under subsection (2) may, in particular, include any savings from the effect of any amendment or repeal or revocation made by this Act. Nothing in Schedule 11 limits the power conferred by subsection (2); and such an order may, in particular, make modifications of that Schedule. Nothing in that Schedule, or in any provision made by virtue of subsection (2), prejudices the operation of sections 16 and 17 of the Interpretation Act 1978 (c. No order under subsection (2) which contains provisions in the form of amendments or repeals of any provision contained in any of paragraphs 30 to 35, 50 and 51 of Schedule 11 is to be made unless a draft of the statutory instrument containing it has been laid before, and approved by a resolution of, each House of Parliament. A statutory instrument containing an order under subsection (2) is (unless a draft of the statutory instrument has been approved by a resolution of each House of Parliament) subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament. Repeals and revocations For repeals and revocations of enactments (including some spent enactments) see Schedule 12. There are to be paid into the Consolidated Fund any sums received by a Minister of the Crown by virtue of this Act (other than any required to be paid into the National Loans Fund). The amendments, and repeals and revocations, made by this Act have the same extent as the enactments amended or repealed or revoked. In this matter "local authorities" means the councils of counties and county boroughs in Wales. In this matter "children" and "young persons" have the same meaning as in field 15. Interpretation of this field Expressions used in this field and in the Education Act 1996 have the same meaning in this field as in that Act. For the purposes of the above definition of "relevant independent educational institution", an institution provides "part-time" education for a person if- a. References in this field to an institution concerned with the provision of further education are references to an educational institution, other than a school or an institution within the higher education sector (within the meaning of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992), that is conducted (whether or not exclusively) for the purpose of providing further education. Definitions 1: Meaning of "pollution" In this field "pollution" means pollution of the air, water or land which may give rise to any environmental harm, including (but not limited to) pollution caused by light, noise, heat or vibrations or any other kind of release of energy. For the purposes of this definition "air" includes (but is not limited to) air within buildings and air within other natural or man-made structures above or below ground. Meaning of "nuisance" In this field "nuisance" means an act or omission affecting any place, or a state of affairs in any place, which may impair, or interfere with, the amenity of the environment or any legitimate use of the environment, apart from an act, omission or state of affairs that constitutes pollution. In those definitions, a reference to the scope of the unlawful nuisance is a reference to the class of acts, omissions and states of affairs that constitutes the unlawful nuisance. Field 7: fire and rescue services and promotion of fire safety Field 8: food Field 9: health and health services Matter 9. For the purposes of this matter, "treatment of mental disorder" means treatment to alleviate, or prevent a worsening of, a mental disorder or one or more of its symptoms or manifestations; and it includes (but is not limited to) nursing, psychological intervention, habilitation, rehabilitation and care. Welsh services provided under a franchise agreement to which the Welsh Ministers are a party. Any expression which is used in paragraph (b) and the Railways Act 2005 has the meaning given in that Act. Chapter 4 of Part 2 of the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008 (insofar as the disposal does not fall within paragraph (a) or (b) of this matter). This matter includes, in particular, advice and non-financial assistance in respect of skills that are relevant to the ability to live independently, or more independently, in housing. Arrangements by principal councils with respect to the discharge of their functions, including executive arrangements. This matter does not include committees under section 19 of the Police and Justice Act 2006 (crime and disorder committees). This matter applies to powers to do anything which the holder of the power considers likely to promote or improve the economic, social or environmental well-being of an area. Interpretation of this field In this field-"communities" means separate areas for the administration of local government, each of which is wholly within a principal area (but does not constitute the whole of a principal area);"principal area" means a county borough or a county;"principal council" means a council for a principal area. This matter applies to the functions of public authorities whose pricipal functions relate to any one or more of the fields in this Part. This matter does not include the independent mental capacity advocacy services established by Part 1 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. In this matter the reference to land at the coast is not limited to coastal land within the meaning of section 3 of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000. This matter does not include licensing of sale and supply of alcohol, provision of entertainment and late night refreshment. This does not include provision about the status to be given to any such plans in connection with the decision on an application for an order granting development consent under the Planning Act 2008.

Licensing and regulation of any licensed water supplier within the meaning of the Water Industry Act 1991 (c menopause bloating buy fertomid 50 mg on-line. A provision of an Act of the Assembly cannot remove or modify menstrual question purchase fertomid 50mg with mastercard, or confer power by subordinate legislation to remove or modify women's health exercise videos buy generic fertomid 50 mg on line, any pre-commencement function of a Minister of the Crown women's health clinic in toronto buy 50mg fertomid overnight delivery. A provision of an Act of the Assembly cannot confer or impose menstruation 2 months buy cheap fertomid 50mg on line, or confer power by subordinate legislation to confer or impose menopause 24 trusted fertomid 50 mg, any function on a Minister of the Crown. In this Schedule "pre-commencement function" means a function which is exercisable by a Minister of the Crown before the day on which the Assembly Act provisions come into force. A provision of an Act of the Assembly cannot make modifications of, or confer power by subordinate legislation to make modifications of, any of the provisions listed in the Table below- Key: Column 1 = Enactment; Column 2 = Provisions protected from modification Row 1 Columnn 1 European Communities Act 1972 (c. Sub-paragraph (1) does not apply to any provision making modifications, or conferring power by subordinate legislation to make modifications, of section 31(6) of the Data Protection Act 1998 so that it applies to complaints under an enactment relating to the provision of redress for negligence in connection with the diagnosis of illness or the care or treatment of any patient (in Wales or elsewhere) as part of the health service in Wales. Sub-paragraph (1), so far as it applies in relation to sections 145, 145A and 146A(1) of the Government of Wales Act 1998, does not apply to a provision to which sub-paragraph (4) applies. A provision of an Act of the Assembly cannot make modifications of, or confer power by subordinate legislation to make modifications of, any provision of an Act of Parliament other than this Act which requires sums required for the repayment of, or the payment of interest on, amounts borrowed by the Welsh Ministers to be charged on the Welsh Consolidated Fund. A provision of an Act of the Assembly cannot make modifications of, or confer power by subordinate legislation to make modifications of, any functions of the Comptroller and Auditor General or the National Audit Ofice. A provision of an Act of the Assembly cannot make modifications of, or confer power by subordinate legislation to make modifications of, provisions contained in this Act. Part 2 does not prevent a provision of an Act of the Assembly removing or modifying, or conferring power by subordinate legislation to remove or modify, any pre-commencement function of a Minister of the Crown if- a. Part 2 does not prevent a provision of an Act of the Assembly conferring or imposing, or conferring power by subordinate legislation to confer or impose, any function on a Minister of the Crown if the Secretary of State consents to the provision. Part 2 does not prevent a provision of an Act of the Assembly modifying, or conferring power by subordinate legislation to modify, any enactment relating to the Comptroller and Auditor General or the National Audit Office if the Secretary of State consents to the provision. Part 2 does not prevent an Act of the Assembly making modifications of, or conferring power by subordinate legislation to make modifications of, an enactment for or in connection with any of the following purposes- a. In this Schedule "civil proceedings" means proceedings other than criminal proceedings. A devolution issue is not to be taken to arise in any proceedings merely because of any contention of a party to the proceedings which appears to the court or tribunal before which the proceedings take place to be frivolous or vexatious. This Part applies in relation to devolution issues in proceedings in England and Wales. Proceedings for the determination of a devolution issue may be instituted by the Attorney General or the Counsel General. The Counsel General may defend any such proceedings instituted by the Attorney General. This paragraph does not limit any power to institute or defend proceedings exercisable apart from this paragraph by any person. A court or tribunal must order notice of any devolution issue which arises in any proceedings before it to be given to the Attorney General and the Counsel General (unless a party to the proceedings). A court may refer any devolution issue which arises in civil proceedings before it to the Court of Appeal. A tribunal from which there is no appeal must refer any devolution issue which arises in proceedings before it to the Court of Appeal; and any other tribunal may make such a reference. A court, other than the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court, may refer any devolution issue which arises in criminal proceedings before it to- a. The Court of Appeal may refer any devolution issue which arises in proceedings before it (otherwise than on a reference under paragraph 7, 8 or 9) to the Supreme Court. An appeal against a determination of a devolution issue by the High Court or the Court of Appeal on a reference under paragraph 6, 7, 8 or 9 lies to the Supreme Court but only- a. Proceedings for the determination of a devolution issue may be instituted by the Advocate General for Scotland. The Counsel General may defend any such proceedings instituted by the Advocate General for Scotland. A court or tribunal must order intimation of any devolution issue which arises in any proceedings before it to be given to the Advocate General for Scotland and the Counsel General (unless a party to the proceedings). A person to whom notice is given in pursuance of sub-paragraph (1) may take part as a party in the proceedings, so far as they relate to a devolution issue. A court, other than any court consisting of three or more judges of the Court of Session or the Supreme Court, may refer any devolution issue which arises in civil proceedings before it to the Inner House of the Court of Session. A tribunal from which there is no appeal must refer any devolution issue which arises in proceedings before it to the Inner House of the Court of Session; and any other tribunal may make such a reference. Any court consisting of three or more judges of the Court of Session may refer any devolution issue which arises in proceedings before it (otherwise than on a reference under paragraph 15 or 16) to the Supreme Court. Any court consisting of two or more judges of the High Court of Justiciary may refer any devolution issue which arises in proceedings before it (otherwise than on a reference under paragraph 17) to the Supreme Court. An appeal against a determination of a devolution issue by the Inner House of the Court of Session on a reference under paragraph 15 or 16 lies to the Supreme Court. This Part applies in relation to devolution issues in proceedings in Northern Ireland. The Counsel General may defend any such proceedings instituted by the Advocate General for Northern Ireland. A court or tribunal must order notice of any devolution issue which arises in any proceedings before it to be given to the Advocate General for Northern Ireland and the Counsel General (unless a party to the proceedings). A court, other than the Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland or the Supreme Court, may refer any devolution issue which arises in any proceedings before it to the Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland. A tribunal from which there is no appeal must refer any devolution issue which arises in proceedings before it to the Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland; and any other tribunal may make such a reference. The Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland may refer any devolution issue which arises in proceedings before it (otherwise than on a reference under paragraph 25 or 26) to the Supreme Court. An appeal against a determination of a devolution issue by the Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland on a reference under paragraph 25 or 26 lies to the Supreme Court but only- a. The relevant officer may require any court or tribunal to refer to the Supreme Court any devolution issue which has arisen in any proceedings before it to which that person is a party. The Attorney General or the Counsel General may refer to the Supreme Court any devolution issue which is not the subject of proceedings. Where a reference is made under sub-paragraph (1) by the Attorney General in relation to a devolution issue which relates to the proposed exercise of a function by the Welsh Ministers, the First Minister or the Counsel General- a. In deciding any such question the court or tribunal may award the whole or part of the additional expense as costs or expenses to the party who incurred it (whatever the decision on the devolution issue). The additional expense is any additional expense which the court or tribunal considers that any party to the proceedings has incurred as a result of the participation of any person in pursuance of paragraph 5, 14 or 24. Any power to make provision for regulating the procedure before any court or tribunal includes power to make provision for the purposes of this Schedule including, in particular, provision- a. Any function conferred by this Schedule to refer a devolution issue to a court is to be construed as a function of referring the issue to the court for decision. Schedules 10-12: [Schedules 10-12 omitted due to length full text of schedules can be found online at. This section applies for the purposes of the Timetable in rule 1 in Schedule 1 to the Representation of the People Act 1983 and is subject to section 2. The polling day for the next parliamentary general election after the passing of this Act is to be 7 May 2015. The polling day for each subsequent parliamentary general election is to be the first Thursday in May in the fifth calendar year following that in which the polling day for the previous parliamentary general election fell. The Prime Minister may by order made by statutory instrument provide that the polling day for a parliamentary general election in a specified calendar year is to be later than the day determined under subsection (2) or (3), but not more than two months later. A statutory instrument containing an order under subsection (5) may not be made unless a draft has been laid before and approved by a resolution of each House of Parliament. The form of motion for the purposes of subsection (1)(a) is- "That there shall be an early parliamentary general election. If a parliamentary general election is to take place as provided for by subsection (1) or (3), the polling day for the election is to be the day appointed by Her Majesty by proclamation on the recommendation of the Prime Minister (and, accordingly, the appointed day replaces the day which would otherwise have been the polling day for the next election determined under section 1). The Parliament then in existence dissolves at the beginning of the 25th working day before the polling day for the next parliamentary general election as determined under section 1 or appointed under section 2(7). Once Parliament dissolves, the Lord Chancellor and, in relation to Northern Ireland, the Secretary of State have the authority to have the writs for the election sealed and issued (see rule 3 in Schedule 1 to the Representation of the People Act 1983). Once Parliament dissolves, Her Majesty may issue the proclamation summoning the new Parliament which may- a. General election for Scottish Parliament not to fall on same date as parliamentary general election under section 1(2) 1. This section applies in relation to the ordinary general election for membership of the Scottish Parliament the poll for which would, apart from this section and disregarding sections 2(5) and 3(3) of the Scotland Act 1998, be held on 7 May 2015 (that is, the date specified in section 1(2) of this Act). Section 2(2) of the 1998 Act has effect as if, instead of providing for the poll for that election to be held on that date, it provided (subject to sections 2(5) and 3(3) of that Act) for the poll to be held on 5 May 2016 (and section 2(2) has effect in relation to subsequent ordinary general elections accordingly). General election for National Assembly for Wales not to fall on same date as parliamentary general election under section 1(2) 1. This section applies in relation to the ordinary general election for membership of the National Assembly for Wales the poll for which would, apart from this section and disregarding sections 4 and 5(5) of the Government of Wales Act 2006, be held on 7 May 2015 (that is, the date specified in section 1(2) of this Act). Section 3(1) of the 2006 Act has effect as if, instead of providing for the poll for that election to be held on that date, it provided (subject to sections 4 and 5(5) of that Act) for the poll to be held on 5 May 2016 (and section 3(1) has effect in relation to subsequent ordinary general elections accordingly). This Act does not affect the way in which the sealing of a proclamation summoning a new Parliament may be authorised; and the sealing of a proclamation to be issued under section 2(7) may be authorised in the same way. An amendment or repeal made by this Act has the same extent as the enactment or relevant part of the enactment to which the amendment or repeal relates. A majority of the members of the committee are to be members of the House of Commons. Arrangements under subsection (4)(a) are to be made no earlier than 1 June 2020 and no later than 30 November 2020. Contents Preface by Klaus Schwab v Executive Summary At a Glance: the Global Competitiveness Index 4. In this context, the World Economic Forum introduced last year the new Global Competitiveness Index 4. The index is an annual yardstick for policy-makers to look beyond short-term and reactionary measures and to instead assess their progress against the full set of factors that determine productivity. The report demonstrates that 10 years on from the financial crisis, while central banks have injected nearly 10 trillion dollars into the global economy, productivity-enhancing investments such as new infrastructure, R&D and skills development in the current and future workforce have been suboptimal. As monetary policies begin to run out of steam, it is crucial for economies to rely on fiscal policy, structural reforms and public incentives to allocate more resources towards the full range of factors of productivity to fully leverage the new opportunities provided by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The report also looks to the future, specifically the two defining issues of the next decade-building shared prosperity and managing the transition to a sustainable economy-and poses the question of their compatibility with competitiveness and growth. There is already a clear moral case for a focus on the environment and on inequality. The report demonstrates that there are no inherent trade-offs between economic growth and social and environmental factors if we adopt a holistic and longer-term approach. While few economies are currently pursuing such an approach, it has become imperative for all economies to develop new inclusive and sustainable pathways to economic growth if we are to meet the Sustainable Development Goals. Bold leadership and proactive policy-making will be necessary, often in areas where economists and public policy professionals cannot provide evidence from the past. The report showcases the most promising emerging pathways, policies and incentives by identifying "win-win" spaces, but also points to the choices and decisions that leaders must make in sequencing the journey towards the three objectives of growth, inclusion and sustainability. By combining insight, models and action the Platform serves as an accelerator for emerging solutions, pilots and partnerships. We invite leaders to join us to co-shape new solutions to the challenges highlighted in this report, working together with the urgency and ambition that the current context demands of us. I want to express my gratitude to the core project team involved in the production of this report: Sophie Brown, Roberto Crotti, Thierry Geiger, Guillaume Hingel, Saadia Zahidi and other colleagues from the Platform for Shaping the Future of the New Economy and Society. My deep gratitude goes to Professor Xavier Sala-iMartin for his guidance and to the experts, practitioners and governments who were consulted. The Global Competitiveness Report is designed to help policy-makers, business leaders and other stakeholders shape their economic strategies in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. We hope it will also serve as a call to action to engage in the visionary and bold leadership required to build a new economic agenda for growing, sustainable and inclusive economies that provide opportunity for all. The Global Competitiveness Report 2019 v Executive Summary the 2019 edition of the Global Competitiveness Report series, first launched in 1979, features the Global Competitiveness Index 4. Drawing on these results, the report provides leads to unlock economic growth, which remains crucial for improving living standards. In addition, in a special thematic chapter, the report explores the relationship between competitiveness, shared prosperity and environmental sustainability, showing that there is no inherent trade-off between building competitiveness, creating more equitable societies that provide opportunity for all and transitioning to environmentally sustainable systems. However, for a new inclusive and sustainable system, bold leadership and proactive policy-making will be needed, often in areas where economists and public policy professionals cannot provide evidence from the past. Each country should aim to move closer to the frontier on each component of the index. This approach emphasizes that competitiveness is not a zero-sum game between countries-it is achievable for all countries. To put it simply, how efficiently units of labour and capital are combined for generating output. Global Findings and Implications Enhancing competitiveness is still key for improving living standards Sustained economic growth remains a critical pathway out of poverty and a core driver of human development. In fact, there is overwhelming evidence that growth has been the most effective way to lift people out of poverty and improve their quality of life. It is clear that for most of the past decade, growth has been subdued and has remained below potential in many developing countries. Productivity growth started slowing down well before the financial crisis and had decelerated in its aftermath. The financial crisis may have contributed to this deceleration through "productivity hysteresis". Furthermore, beyond strengthening financial system regulations, many of the structural reforms designed to revive productivity did not materialize.

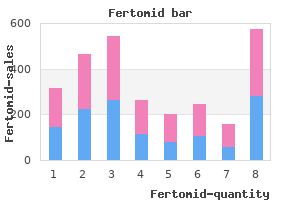

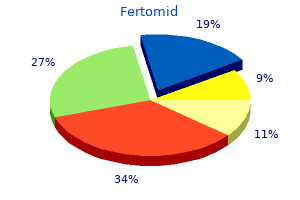

For more detailed information on ethnicity and substance abuse women's health big book of yoga pdf order 50mg fertomid with mastercard, refer to chapter 6 women's health issues powerpoint generic 50 mg fertomid amex. Figure 2-6 shows the percentage of treatment admissions by substance for each ethnic or racial group of women menstruation 9 tage purchase 50mg fertomid free shipping. African-American women were more likely to name crack/cocaine as the primary substance of abuse women's health clinic derby buy fertomid 50 mg online, whereas some subgroups of Hispanic/Latina women were more likely to enter treatment for heroin use menstruation after tubal ligation cheap 50 mg fertomid otc. For most ethnic or racial groups women's health clinic edinburg tx buy cheap fertomid 50mg on-line, alcohol and a secondary drug were abused by the next largest percentage of women. Depending on treatment level, admission rates varied from 29 percent in hospital inpatient facilities to 39 percent in outpatient methadone programs. Compared with the women in treatment who were not pregnant at admission, the pregnant women in treatment were more likely to report cocaine/crack (22 versus 17 percent), amphetamine/methamphetamine (21 versus 13 percent), or marijuana (17 versus 13 percent) as their primary substance of abuse. Alcohol was the primary substance of abuse among almost one-third of women aged 15 to 44 (31 percent) who were not pregnant at the time of admission. In contrast, only 18 percent of women who were pregnant at admission reported alcohol as their primary substance of abuse. Figure 2-5 Percentage of Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Programs by Racial/Ethnic Group in 2006 Group Female Admissions Caucasian Percentage of Total Admissions 31. Women are socialized to assume more caregiver roles and to focus attention on others. Even if she has not appropriately cared for others (such as her children) during her addiction, it does not mean that she will not see this as an important issue immediately upon entering a detoxification or treatment program. Figure 2-6 Primary Substance of Abuse Among Women Admitted for Substance Abuse Treatment by Racial/Ethnic Group by Percentage Substance of Abuse Alcohol Cauca sian 35. From absorption to metabolic processes, women display more difficulty in physically managing the consequences of use. In general, with higher levels of alcohol and drugs in the system for longer periods of time, women are also more susceptible to alcohol- and drug-related diseases and organ damage. This chapter provides an overview of the physiological impact of alcohol and drugs on women, with particular emphasis on the significant physiological differences and consequences of substance use in women. It begins with a general exploration of how gender differences affect the way alcohol and drugs are metabolized in the body and then highlights several biopsychosocial and cultural factors that can influence health issues associated with drugs and alcohol. The chapter goes on to explore the physiological effects of alcohol, drugs (both licit and illicit), and tobacco on the female body. Counselors can use the information presented in this chapter to educate their female clients about the negative effects substances can have on their physical health. A sample patient lecture is included that highlights the physiological effects of heavy alcohol use. Physiological Effects of Alcohol, Drugs, and Tobacco on Women 37 Physiological Effects and Consequences of Substance Abuse in Women Alcohol and drugs can take a heavy toll on the human body. Yet women have different physical responses to substances and greater susceptibility to healthrelated issues. Women differ from men in the severity of the problems that develop from use of alcohol and drugs and in the amount of time be tween initial use and the development of physi ological problems (Greenfield 1996; Mucha et al. For example, a consequence of excessive alcohol use is liver damage (such as cirrhosis) that often begins earlier in women consuming less alcohol over a shorter period of time. By and large, women who have substance use dis orders have poorer quality of life than men on health-related issues. In addition, women who abuse substances have physiological consequences, health issues, and medical needs related to gynecology (Peters et al. Women sometimes use illicit drugs and alcohol as medi cation for cramping, body aches, and other dis comforts associated with menstruation (Stevens and Estrada 1999). On the other hand, women who use heroin and methadone can experience amenorrhea (absence of menstrual periods; Abs et al. Limitations of Current Research on Gender Differences in Metabolism In general, research on the unique physiological effects of alcohol and drugs in women is lim ited and sometimes inconclusive. Although the differences in the way women and men metabo lize alcohol have been studied in some depth, research on differences in metabolism of illicit drugs is limited. For many years, much of the research on metabolism of substances either used male subjects exclusively or did not report on gender differences. Available research is typically based on small sample sizes and has not been replicated. Race and ethnic background can affect metabolism and the psychological effects of alcohol and il licit drugs, as can the psychopharmaceuticals sometimes used in treatment (Rouse et al. Polysubstance use complicates the ability to study and understand the physiological effects of specific drugs on women, while increasing the risk associated with synergistic effects when substances are combined. Physiological Effects: Factors of Influence Ethnicity and Culture the level of acculturation and cultural roles and expectations play a significant role in substance use patterns among women of color (Caetano et al. The prevalence of substance abuse among ethnic women typically coincides with higher levels of acculturation in the United States, thus leading to greater health issues. These health disparities arise from many sources, including difficulty in accessing affordable health care, delays in seeking treatment, limited socioeco nomic resources, racism, and discrimination (Gee 2002; Mays et al. In addition, mistrust of health care providers is a significant barrier to receiving appropriate screening, preventive care, timely interventions, and adequate treatment (Alegria et al. More recent studies have explored the role of gender in perceived discrimination and health, and some studies have noted differences in the type of stressors, reactions, and health conse quences between men and women (Finch et al. More than ethnicity, socioeconomic status heavily influ ences the health risks associated with substance abuse. Research suggests that when the socio economic conditions of ethnically diverse popu lations are similar to those of the White popu lation, consequences of substance use appear comparable (Jones-Webb et al. Among women, alcohol and drug-related morbidity and mortality are disproportionately higher in individuals of lower socioeconomic status, which is associated with insufficient healthcare ser vices, difficulties in accessing treatment, lack of appropriate nutrition, and inadequate prenatal care. Subsequently, impoverished women who abuse substances often experience greater health consequences and poorer health outcomes. Similarly, homelessness is associated with higher mortality rates for all life-threatening disorders, including greater risks for infectious diseases. Sexual Orientation Lesbian/bisexual women exhibit more prevalent use of alcohol, marijuana, prescription drugs, and tobacco than heterosexual women, and they are likely to consume alcohol more frequently and in greater amounts (Case et al. Likewise, they are less likely to have health insurance and to use preventive screen ings, including mammograms and pelvic exami nations. With less utilization of routine screen ings, lesbians and bisexual women may not be afforded the benefit of early detection across disorders, including substance use disorders, breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Developmental Issues and Aging Although little is known regarding the effect of alcohol and drugs on development across the lifespan, there is some evidence in alcohol-relat ed research that there are different vulnerabili ties at different ages for women. Even though developmental research on alcohol is not easily transferred to other drugs of abuse, it can give us a glimpse of the potential physiological issues associated with age and aging. For example, ado lescent women are more likely than their male counterparts to experience cognitive impairment Physiological Effects of Alcohol, Drugs, and Tobacco on Women 39 despite less alcohol consumption. Women of child-bearing age are more likely to experience infertility with heavier drinking (Tolstrup et al. Postmenopausal women are more likely to exhibit significant hormonal changes with heavy consumption of alcohol, leading to poten tially higher risks for breast cancer, osteopo rosis, and coronary heart disease (Weiderpass et al. While research has been more devoted to examining gender dif ferences, limited data are available for other substances and less is known regarding the effect of these substances on development and aging. Compared with men, women become more cognitively impaired by alcohol and are more susceptible to alcoholrelated organ damage. Women develop damage at lower levels of consumption over a shorter period of time (for review, see Antai-Otong 2006). When men and women of the same weight consume equal amounts of alcohol, women have higher blood alcohol concentrations. Women have proportionately more body fat and a lower volume of body water compared with men of similar weight (Romach and Sellers 1998). As a result, women have a higher concentration of alcohol because there is less volume of water to dilute it. In comparison with men, women, at least those younger than 50, have a lower first-pass metabo lism of alcohol in the stomach and upper small intestine before it enters the bloodstream and reaches other body organs, including the liver. These factors may be responsible for the in creased severity, greater number, and faster rate of development of complications that women experience from alcohol abuse when compared with men, according to reviews of several studies (Blum et al. Women de velop alcohol abuse and dependence in less time than do men, a phenomenon known as telescop ing (Piazza et al. At a rate of consumption of two to three standard drinks per day, women have a higher mortality rate than men who drink the same amount. Men do not experience an increased mortality risk until they consume four drinks daily (Holman et al. Co-occurring disorders have a bidi rectional relationship and often a synergistic ef fect on one another. As much as substance abuse can increase the risk of, exacerbate, or cause medical conditions, medical disorders can also increase substance abuse as a means of self-med icating symptoms or mental distress associated with the disorder. Similar to men, women who have mental disorders can have more difficulty adhering to health-related treatment recom mendations, such as treatment attendance, diet restrictions, or medication compliance. Physiological Effects of Alcohol Gender Differences in Metabolism and Effects Alcohol is a leading cause of mortality and disability worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, alcohol is one of the five 40 Physiological Effects of Alcohol, Drugs, and Tobacco on Women Women develop other alcohol-related diseases at a lower total lifetime exposure than men, includ ing such disorders as fatty liver, hypertension, obesity, anemia, malnutrition, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and ulcers that require surgery (Van Thiel et al. Heavy alcohol use also increases the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, ac cording to one study cited by Nanchahal and colleagues (2000). The following sections identify specific physi ological effects related to alcohol use by women. These effects are not distinct from one another; rather, they interact in a synergistic way in the body. Heavy consumption (more than four drinks per day) is associated with increased blood pressure in both women and men (Bradley et al. The female heart appears to experience a functional decline at a lower level of lifetime exposure to alcohol than does the male heart (Urbano-Marquez et al. These differences stem from gender differences in body composition and metabolism. Liver and Other Organ Damage Females are more likely than their male coun terparts to experience greater organ damage as a result of consuming similar amounts of alcohol. Compared with men, women develop alcoholinduced liver disease over a shorter period of time and after consuming less alcohol (Gavaler and Arria 1995). Women are more likely than men to develop alcoholic hepatitis and to die from cirrhosis (Hall 1995). Reproductive Consequences Research into the adverse impact of alcohol con sumption on fertility is growing. While numer ous studies have shown a consistent relationship between heavy drinking and infertility (Eggert et al. Nevertheless, findings suggest a need to educate and screen women for alcohol use while they are seeking infertility treatment (Chang et al. In addition, heavy drink ing is associated with painful and/or irregular menstruation (Bradley et al. The repro- Cardiac-Related Conditions According to current studies, women who drink exhibit a greater propensity to develop alcoholinduced cardiac damage. While light consump tion (less than one drink per day) can serve as a protective factor for women who have a risk for coronary artery disease, studies suggest that protection is not evident for younger women, women who drink heavily, and women without risk factors associated with heart disease. Wom Physiological Effects of Alcohol, Drugs, and Tobacco on Women 41 ductive consequences associated with alcohol use disorders range from increased risk for miscar riage to impaired fetal growth and development (Mello et al. There are considerable variations among women in their capacity to consume and metabolize alcohol. Early literature suggests that variations in alcohol metabolism among women may be linked to the different phases of the menstrual cycle, but more recent reviews suggest that there are no consistent effects of the menstrual cycle on the subjective experience of alcohol intake or alcohol metabolism (Terner and de Wit 2006). Studies reviewed by Romach and Sellers (1998) found that significant hormonal changes are re ported in postmenopausal women who consume alcohol. These high levels are associated with a greater risk of breast cancer and coro nary heart disease. While the risk for in situ and invasive cervical cancer and cancer of the vagina may be associ ated with other environmental factors including high-risk sexual behavior, human papilloma vi ruses, smoking, hormonal therapy, and dietary deficiency, Weiderpass and colleagues (2001) concluded, based on 30 years of retrospective data, that women who are alcohol dependent are at a higher risk for developing these cancers. Although further investiga tion is needed to explore the role of alcohol consumption on gastric cancer, preliminary findings suggest that the type of alcoholic bever age, namely medium-strength beer, creates an increased risk of gastric cancer (Larsson et al. Based on a multiethnic cohort study, the risk of endometrial cancer increases when postmenopausal women consume an average of two or more drinks per day (Setiawan et al. Additional risks are associated with tobacco use, particularly for cancers of the upper digestive and respiratory tract. Breast and Other Cancers Numerous studies have documented associations and suggested causal relationships between al cohol consumption and breast cancer risk (Key et al. A review of data from more than 50 epidemio logical studies from around the world revealed that for each drink of alcohol consumed daily, women increased their risk of breast cancer by 7 percent (Hamajima et al. Postmenopausal women have an increased risk of breast cancer as well if they currently drink alcohol (Lenz et al. Women who drink alcohol have elevated estrogen and andro gen levels, which are hypothesized to be con tributors to the development of breast cancer in this population (Singletary and Gapstur 2001). In addition, postmenopausal women who are moderate alcohol drinkers (one to two drinks a day) and who are using menopausal hormone therapy have an increased risk of breast cancer, with even greater risk at higher rates of alcohol consumption (Dorgan et al. Heavy alcohol use clearly has been shown to harm bones and to increase the risk of osteoporosis by decreasing bone density. These effects are especially strik ing in young women, whose bones are develop ing, but chronic alcohol use in adulthood also harms bones (Sampson 2002).

Syndromes

All studies relied on qualitative or semiquantitative methods to assign exposure histories to subjects women's health center greensburg pa purchase 50mg fertomid fast delivery. Semi-quantitative methods included the use of leaching and transport models to estimate amounts of tetrachloroethylene delivered to residential supply lines along with self-reported information on residence addresses during the applicable exposure period menopause kim cattrall discount 50mg fertomid with amex. Non-differential exposure misclassification (misclassification rate is the same among exposure groups) will tend to bias the estimates of relative risk downward women's health center santa rosa purchase fertomid 50 mg on-line. However women's health questions to ask your doctor cheap fertomid 50 mg with amex, differential exposure misclassification could bias the risk estimates in the up or down direction menopause 43 purchase 50mg fertomid amex. For studies evaluating males and females separately (with no combined group) menopause the musical laguna beach purchase fertomid 50mg mastercard, data for both are presented. Less data are available for other cancer types (and all cancers and cancers of the bladder, kidney, liver, pancreas, lung, colon, rectum, brain/central nervous system, cervix, and prostate). Cancer has been reported in experimental animals after oral exposure to tetrachloroethylene. The elevated early mortality, which occurred at both doses in both sexes of rats and mice, was related to compound-induced toxic nephropathy (see Section 3. Because of reduced survival, this study was not considered adequate for evaluation of carcinogenesis in rats. Statistically significant increases in hepatocellular carcinomas occurred in the treated mice of both sexes. Incidences in the untreated control, vehicle control, low-dose, and high-dose groups were 2/17, 2/20, 32/49, and 27/48, respectively, in male mice, and 2/20, 0/20, 19/48, and 19/48, respectively, in female mice. Study limitations included control groups smaller than treated groups (20 versus 50), numerous dose adjustments during the study, early mortality related to compound-induced toxic nephropathy (suggesting that a maximum tolerated dose was exceeded), and pneumonia due to intercurrent infectious disease (murine respiratory mycoplasmosis) in both rats and mice. Because of its carcinogenic activity in mouse liver, tetrachloroethylene has been tested for initiating and promoting activity in a rat liver foci assay. All five rabbits treated with a single dermal dose of 3,245 mg/kg tetrachloroethylene that was occluded for 24 hours survived (Kinkead and Leahy 1987). Additional studies regarding death following dermal exposure in animals were not located. Hypotension was reported in a male laundry worker found lying in a pool of tetrachloroethylene (Hake and Stewart 1977). In this case, the worker was exposed to tetrachloroethylene by both inhalation and dermal routes of exposure, and the exact contribution of dermal exposure is unknown. No studies were located regarding cardiovascular effects in animals after dermal exposure to tetrachloroethylene. Elevated serum enzymes (not further described) indicative of mild liver injury were observed in an individual found lying in a pool of tetrachloroethylene (Hake and Stewart 1977). No studies were located regarding hepatic effects in animals after dermal exposure to tetrachloroethylene. Proteinuria, which lasted for 20 days, was observed in an individual found lying in a pool of tetrachloroethylene (Hake and Stewart 1977). Exposure in this case was by both the inhalation and dermal routes, and the exact contribution of dermal exposure is unknown. No studies were located regarding renal effects in animals after dermal exposure to tetrachloroethylene. Five volunteers placed their thumbs in beakers of tetrachloroethylene for 30 minutes (Stewart and Dodd 1964). After the thumb was removed from the solvent, the burning decreased during the next 10 minutes. Chemical burns characterized by severe cutaneous erythema, blistering, and sloughing resulted from prolonged (more than 5 hours) accidental contact exposure to tetrachloroethylene used in dry cleaning operations (Hake and Stewart 1977; Ling and Lindsay 1971; Morgan 1969). The animals did not develop toxic signs, and skin lesions were not reported (Kinkead and Leahy 1987). Intense ocular irritation has been reported in humans after acute exposure to tetrachloroethylene vapor at concentrations >1,000 ppm (Carpenter 1937; Rowe et al. Vapors of tetrachloroethylene at 5 or 20 ppm were irradiated along with nitrogen dioxide in an environmental chamber in order to simulate the atmospheric conditions of Los Angeles County. These conditions did not produce appreciable eye irritation in volunteers exposed to the simulated atmosphere (Wayne and Orcutt 1960). No studies were located regarding ocular effects in animals after dermal exposure to tetrachloroethylene including direct application to the eye. The exposure to tetrachloroethylene in this case was by both the inhalation and dermal routes, and the exact contribution of dermal exposure is unknown. No studies were located regarding neurological effects in animals after dermal exposure to tetrachloroethylene. Data from these assays indicate that tetrachloroethylene has the potential to be genotoxic. An evaluation of the genotoxic potential of tetrachloroethylene in vitro suggests that tetrachloroethylene is unlikely to induce reverse mutations in Salmonella typhimurium; however, positive responses have been observed under some conditions (possibly due to metabolites and/or contaminants). The study population consisted of 30 workers and 29 controls; no differences between groups were observed for age, smoking, or alcohol consumption. Exposure monitoring was conducted by sampling of personal breathing zone air on two consecutive work days, with a mean tetrachloroethylene concentration of 31. The frequency of micronuclei formation, an indicator of chromosome damage, was significantly increased in workers compared to controls (workers: 11. However, the chromosome aberration frequency was not significantly increased in workers, although multiple regression analysis showed associations between employment duration (p=0. The median duration of employment was 8 years, with a minimum duration of 3 months. Compared to controls (n=26), workers exposed to tetrachloroethylene had significantly (p<0. Increases in chromosome aberrations and sister chromatid exchanges were not detected in lymphocytes from 10 workers who were occupationally exposed to tetrachloroethylene (Ikeda et al. The exposure concentrations for these workers were estimated to be between 10 and 220 ppm for 3 months to 18 years. The small number of workers and the wide range of exposure concentrations and durations limit the generalizations that can be made from this study. Although the study authors had found no significant effect of cigarette smoking alone in either the exposed workers or the controls, the difference in sister chromatid exchange frequency between the exposed workers who smoked and the nonsmoking controls was statistically significant. The authors proposed a synergistic effect of chemical exposure and cigarette smoking. The number of workers examined was small (12 smokers and 2 nonsmokers among the exposed men; 9 smokers and 3 nonsmokers among the controls). Chromosomal damage was not significantly changed based on cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption. Although the sample sizes were small, no acentric fragments were observed in unexposed laundry workers. In comet assays, a weak but significant, dose-related increase in tail intensity, but not tail moment, was reported in hepatocytes (p=0. Although the study authors classified the response in the liver as "positive," these data, when analyzed in the context of biological relevance by the lab that conducted the experiment and by Lillford et al. Micronuclei were increased in hepatocytes at 1,000 and 2,000 mg/kg when mice were treated after partial hepatectomy. A large number of studies of in vitro genotoxicity of tetrachloroethylene have been performed using prokaryotic, eukaryotic, and mammalian cells (Table 3-6). Several chlorinated aliphatic compounds identified in the spent liquor from the softwood kraft pulping process were found to be mutagenic (Kringstad et al. Tetrachloroethylene was one of several compounds isolated that was shown to be mutagenic for S. In contrast, purified tetrachloroethylene was not mutagenic with or without exogenous metabolic activation. However, preincubation of tetrachloroethylene with purified rat liver glutathione S-transferases in the presence of glutathione and rat kidney fraction resulted in the formation of the conjugate, S-(1,2,2-trichlorovinyl)glutathione, which was unequivocally mutagenic in the Ames test (Vamvakas et al. Tetrachloroethylene oxide, an epoxide intermediate of tetrachloroethylene, was found to be mutagenic in bacterial studies (Kline et al. Mixed results were obtained in yeast when no metabolic activation was used in the experiments by Bronzetti et al. This study is difficult to interpret because negative results were obtained using the higher concentrations, whereas the lower doses produced a weak positive response. In addition, the positive control chemicals (N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine, benz[a]pyrene) produced only weak positive responses. Most data do not support a directly mutagenic effect of tetrachloroethylene itself. The inconsistent results could be due to differences between tested species in metabolism or activation, protocol differences, or purity of the compound tested. There are few data on clastogenic effects of tetrachloroethylene following in vitro exposure. Mixed results have been reported for micronucleus induction in human lymphocytes and Chinese hamster cell lines. There was no significant induction of micronuclei in Chinese hamster lung cells following exposure to tetrachloroethylene at up to 250 g/mL in the presence or absence of metabolic activation (Matsushima et al. However, Fischer rat embryo cells were transformed in the absence of metabolic activation (Price et al. Pulmonary absorption of tetrachloroethylene is dependent on the ventilation rate, the duration of exposure, and at lower concentrations, the proportion of tetrachloroethylene in the inspired air. Compared to pulmonary exposure, uptake of tetrachloroethylene vapor by the skin is minimal. Because of its affinity for fat, tetrachloroethylene is found in milk, with greater levels in milk with a higher fat content. Tetrachloroethylene has also been shown to cross the placenta and distribute to the fetus. Compared to humans, rodents, especially mice, metabolize more tetrachloroethylene to trichloroacetic acid. Geometric mean Vmax values for the metabolism of tetrachloroethylene of 13, 144, and 710 nmol/(minute/kg) have been reported for humans, rats, and mice, respectively. Trichloroacetic acid produced from tetrachloroethylene is excreted in the urine, and in humans, trichloroacetic acid excretion is linearly related to concentrations of tetrachloroethylene in air at levels up to about 50 ppm. In humans, tetrachloroethylene is readily absorbed into the blood through the lungs. Estimates of human blood:air partition coefficients from in vitro methods are shown in Table 3-8; in large part, these estimates are consistent with the in vivo values. Partition Coefficients for Tetrachloroethylene in Mice, Rats, Dogs, and Humans Partition coefficientsa Mouse Blood/air Blood/air Blood/air Blood/air Blood/air Blood/air Blood/air males females Liver/air Liver/air Liver/air Liver/air Fat/air Fat/air Fat/air Fat/air Vesselrich/air Muscle/air Muscle/air Muscle/air Muscle/air Kidney/air Kidney/air Kidney/air Brain/air Milk/air Liver/blood Liver/blood Liver/blood Liver/blood Fat/blood Fat/blood Fat/blood Fat/blood Muscle/blood Muscle/blood Muscle/blood Kidney/blood 16. Partition Coefficients for Tetrachloroethylene in Mice, Rats, Dogs, and Humans Partition coefficientsa Mouse Rat Dog Human Methodb Intraarterial dosing Oral dosing Intraarterial Oral dosing Intraarterial dosing Oral dosing Intraarterial dosing Oral dosing Smear method Smear method Reference Dallas et al. Partition Coefficients for Tetrachloroethylene in Mice, Rats, Dogs, and Humans Partition coefficientsa Mouse Kidney/air Brain/air aDetermined bExamples Rat 37. After treatment, groups of four rats were sacrificed at 1, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60 minutes and at 2, 4, 6, 12, 36, 48, and 72 hours after dosing. After treatment, groups of four rats were sacrificed at 1, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60 minutes, and 2, 4, 6, 12, 8, 36, 48, and 72 hours after dosing, and groups of three dogs were sacrificed 1, 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours after dosing. In addition, a study of male volunteers showed higher total uptake of inhaled tetrachloroethylene with higher lean body mass; minute volume and adipose tissue did not influence uptake (Monster et al. The rate of tetrachloroethylene uptake by the lungs is initially high, but decreases during exposure (Monster et al. The concentration of tetrachloroethylene in the venous blood of six male volunteers peaked near the end of a 6-hour exposure to 1 ppm, and declined thereafter (Chiu et al. The experiments were designed to assess the relationship between pulmonary uptake and urinary concentration of tetrachloroethylene, and between pulmonary uptake and ventilation and/or retention of the chemical. Urinary concentration of tetrachloroethylene was positively correlated with uptake of the chemical. The retention index decreased with increasing ventilation at rest and during exercise. The urinary concentration of tetrachloroethylene was dependent on ventilation and retention index, increasing when either of these two parameters increased. In the same study, a group of workers occupationally exposed to tetrachloroethylene (occupation not specified) were also monitored to determine if urinary concentration of tetrachloroethylene correlated with environmental exposure. These results suggest that physical activity affects the absorption of tetrachloroethylene and that these variations in absorption are reflected in urinary concentrations of the chemical. Inhalation experiments in animals also indicate that tetrachloroethylene is readily absorbed through the lungs into the blood. Near steady-state breath concentrations in exhaled air were achieved within about 20 minutes and were proportional to concentration (2. The peak blood tetrachloroethylene concentration of 40 g/mL was measured 1 hour after dosing at 500 mg/kg tetrachloroethylene (Pegg et al. In Sprague-Dawley rats and Beagle dogs given a single oral dose of tetrachloroethylene (10 mg/kg in polyethylene glycol 400) by gavage, the absorption constants were estimated to be 0.

Fertomid 50mg with visa. WV women Work.