|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Thomas E. McKone PhD

https://publichealth.berkeley.edu/people/thomas-mckone/

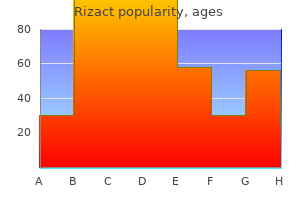

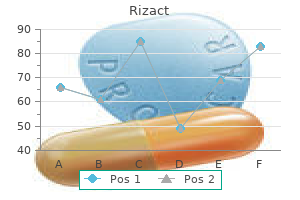

Despite the widespread use of the term pain treatment for endometriosis generic 10mg rizact amex, stress is a fairly vague concept that is difficult to define with precision best pain medication for old dogs discount 5mg rizact amex. Researchers have had a difficult time agreeing on an acceptable definition of stress midsouth pain treatment center reviews discount rizact 10mg with amex. Some have conceptualized stress as a demanding or threatening event or situation pain treatment center mallory lane franklin tn cheap rizact 5 mg visa. Such conceptualizations are known as stimulus-based definitions because they characterize stress as a stimulus that causes certain reactions back pain treatment nhs discount rizact 5 mg free shipping. Stimulus-based definitions of stress are problematic midwest pain treatment center findlay ohio generic 5 mg rizact mastercard, however, because they fail to recognize that people differ in how they view and react to challenging life events and situations. For example, a conscientious student who has studied diligently all semester would likely experience less stress during final exams week than would a less responsible, unprepared student. Others have conceptualized stress in ways that emphasize the physiological responses that occur when faced with demanding or threatening situations. These conceptualizations are referred to as response-based definitions because they describe stress as a response to environmental conditions. For example, the endocrinologist Hans Selye, a famous stress researcher, once defined stress as the "response of the body to any demand, whether it is caused by, or results in, pleasant or unpleasant conditions" (Selye, 1976, p. Neither stimulusbased nor response-based definitions provide a complete definition of stress. Many of the physiological reactions that occur when faced with demanding situations. A useful way to conceptualize stress is to view it as a process whereby an individual perceives and responds to events that he appraises as overwhelming or threatening to his well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). A critical element of this definition is that it emphasizes the importance of how we appraise-that is, judge-demanding or threatening events (often referred to as stressors); these appraisals, in turn, influence our reactions to such events. Two kinds of appraisals of a stressor are especially important in this regard: primary and secondary appraisals. A primary appraisal involves judgment about the degree of potential harm or threat to well-being that a stressor might entail. A stressor would likely be appraised as a threat if one anticipates that it could lead to some kind of harm, loss, or other negative consequence; conversely, a stressor would likely be appraised as a challenge if one believes that it carries the potential for gain or personal growth. For example, an employee who is promoted to a leadership position would likely perceive the promotion as a much greater threat if she believed the promotion would lead to excessive work demands than if she viewed it as an opportunity to gain new skills and grow professionally. Similarly, a college student on the cusp of graduation may face the change this OpenStax book is available for free at cnx. A threat tends to be viewed as less catastrophic if one believes something can be done about it (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Imagine that two middle-aged people Robin and Madhuri, perform breast self-examinations one morning and each notices a lump on the lower region of their left breast. Although both view the breast lump as a potential threat (primary appraisal), their secondary appraisals differ considerably. Although most times these things turn out to be benign, I need to have it checked out. If it turns out to be breast cancer, there are doctors who can take care of it because the medical technology today is quite advanced. Stress is likely to result if a stressor is perceived as extremely threatening or threatening with few or no effective coping options available. To be sure, some stressors are inherently more stressful than others in that they are more threatening and leave less potential for variation in cognitive appraisals. Nevertheless, appraisal will still play a role in augmenting or diminishing our reactions to such events (Everly & Lating, 2002). If a person appraises an event as harmful and believes that the demands imposed by the event exceed the available resources to manage or adapt to it, the person will subjectively experience a state of stress. In contrast, if one does not appraise the same event as harmful or threatening, she is unlikely to experience stress. According to this definition, environmental events trigger stress reactions by the way they are interpreted and the meanings they are assigned. Although stress carries a negative connotation, at times it may be of some benefit. Stress can motivate us to do things in our best interests, such as study for exams, visit the doctor regularly, exercise, and perform to the best of our ability at work. This kind of stress, which Selye called eustress (from the Greek eu = "good"), is a good kind of stress associated with positive feelings, optimal health, and performance. For example, athletes may be motivated and energized by pregame stress, and students may experience similar beneficial stress before a major exam. Indeed, research shows that moderate stress can enhance both immediate and delayed recall of educational material. Male participants in one study who memorized a scientific text passage showed improved memory of the passage immediately after exposure to a mild stressor as well as one day following exposure to the stressor (Hupbach & Fieman, 2012). A person at this stress level is colloquially at the top of his game, meaning he feels fully energized, focused, and can work with minimal effort and maximum efficiency. But when stress exceeds this optimal level, it is no longer a positive force-it becomes excessive and debilitating, or what Selye termed distress (from the Latin dis = "bad"). People who reach this level of stress feel burned out; they are fatigued, exhausted, and their performance begins to decline. If the stress remains excessive, health may begin to erode as well (Everly & Lating, 2002). When students are feeling very stressed about a test, negative emotions combined with physical symptoms may make concentration difficult, thereby negatively affecting test scores. If stress exceeds the optimal level, it will reach the distress region, where it will become excessive and debilitating, and performance will decline (Everly & Lating, 2002). Stress is an experience that evokes a variety of responses, including those that are physiological. Although stress can be positive at times, it can have deleterious health implications, contributing to the onset and progression of a variety of physical illnesses and diseases (Cohen & Herbert, 1996). The scientific study of how stress and other psychological factors impact health falls within the realm of health psychology, a subfield of psychology devoted to understanding the importance of psychological influences on health, illness, and how people respond when they become ill (Taylor, 1999). Health psychology emerged as a discipline in the 1970s, a time during which there was increasing awareness of the role behavioral and lifestyle factors play in the development of illnesses and diseases (Straub, 2007). In addition to studying the connection between stress and illness, health psychologists investigate issues such as why people make certain lifestyle choices. Health psychologists also design and investigate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at changing unhealthy behaviors. Perhaps one of the more fundamental tasks of health psychologists is to identify which groups of people are especially at risk for negative health outcomes, based on psychological or behavioral factors. For example, measuring differences in stress levels among demographic groups and how these levels change over time can help identify populations who may have an increased risk for illness or disease. Unemployed individuals reported high levels of stress in all three surveys, as did those with less education and income; retired persons reported the lowest stress levels. Across categories of sex, age, race, education level, employment status, and income, stress levels generally show a marked increase over this quartercentury time span. One of the early pioneers in the study of stress was Walter Cannon, an eminent American physiologist at Harvard Medical School (Figure 14. Cannon and the Fight-or-Flight Response Imagine that you are hiking in the beautiful mountains of Colorado on a warm and sunny spring day. At one point during your hike, a large, frightening-looking black bear appears from behind a stand of trees and sits about 50 yards from you. In addition to thinking, "This is definitely not good," a constellation of physiological reactions begins to take place inside you. Prompted by a deluge of epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) from your adrenal glands, your pupils begin to dilate. Your heart starts to pound and speeds up, you begin to breathe heavily and perspire, you get butterflies in your stomach, and your muscles become tense, preparing you to take some kind of direct action. Cannon proposed that this reaction, which he called the fight-or-flight response, occurs when a person experiences very strong emotions-especially those associated with a perceived threat (Cannon, 1932). During the fight-or-flight response, the body is rapidly aroused by activation of both the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system (Figure 14. This arousal helps prepare the person to either fight or flee from a perceived threat. Thus, Cannon viewed the fight-or-flight response as adaptive because it enables people to adjust internally and externally to threats in their environment, allowing them to continue to be alive and overcome the threat. Selye and the General Adaptation Syndrome Another important early contributor to the stress field was Hans Selye, mentioned earlier. As a young assistant in the biochemistry department at McGill University in the 1930s, Selye was engaged in research involving sex hormones in rats. Although he was unable to find an answer for what he was initially researching, he incidentally discovered that when exposed to prolonged negative stimulation (stressors)-such as extreme cold, surgical injury, excessive muscular exercise, and shock-the rats showed signs of adrenal enlargement, thymus and lymph node shrinkage, and stomach ulceration. Selye realized that these responses were triggered by a coordinated series of physiological reactions that unfold over time during continued exposure to a stressor. These physiological reactions were nonspecific, which means that regardless of the type of stressor, the same pattern of reactions would occur. In 2009, his native Hungary honored his work with this stamp, released in conjunction with the 2nd annual World Conference on Stress. During an alarm reaction, you are alerted to a stressor, and your body alarms you with a cascade of physiological reactions that provide you with the energy to manage the situation. A person who wakes up in the middle of the night to discover her house is on fire, for example, is experiencing an alarm reaction. If exposure to a stressor is prolonged, the organism will enter the stage of resistance. During this stage, the initial shock of alarm reaction has worn off and the body has adapted to the stressor. Nevertheless, the body also remains on alert and is prepared to respond as it did during the alarm reaction, although with less intensity. Although the parents would obviously remain extremely disturbed, the magnitude of physiological reactions would likely have diminished over the 72 intervening hours due to some adaptation to this event. If exposure to a stressor continues over a longer period of time, the stage of exhaustion ensues. As a result, illness, disease, and other permanent damage to the body-even death-may occur. If a missing child still remained missing after three months, the long-term stress associated with this situation may cause a parent to literally faint with exhaustion at some point or even to develop a serious and irreversible illness. As we shall discuss later, prolonged or repeated stress has been implicated in development of a number of disorders such as hypertension and coronary artery disease. Release of these hormones activates the fight-or-flight responses to stress, such as accelerated heart rate and respiration. Cortisol is commonly known as a stress hormone and helps provide that boost of energy when we first encounter a stressor, preparing us to run away or fight. The hypothalamus activates the pituitary gland, which in turn activates the adrenal glands, increasing their secretion of cortisol. In short bursts, this process can have some favorable effects, such as providing extra energy, improving immune system functioning temporarily, and decreasing pain sensitivity. However, extended release of cortisol-as would happen with prolonged or chronic stress-often comes at a high price. For example, increases in cortisol can significantly weaken our immune system (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005), and high levels are frequently observed among depressed individuals (Geoffroy, Hertzman, Li, & Power, 2013). In summary, a stressful event causes a variety of physiological reactions that activate the adrenal glands, which in turn release epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol. These hormones affect a number of bodily processes in ways that prepare the stressed person to take direct action, but also in ways that may heighten the potential for illness. For example, stress often contributes to the development of certain psychological disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, and other serious psychiatric conditions. Additionally, we noted earlier that stress is linked to the development and progression of a variety of physical illnesses and diseases. For example, researchers in one study found that people injured during the September 11, 2001, World Trade Center disaster or who developed post-traumatic stress symptoms afterward later suffered significantly elevated rates of heart disease (Jordan, Miller-Archie, Cone, Morabia, & Stellman, 2011). Another investigation yielded that self-reported stress symptoms among aging and retired Finnish food industry workers were associated with morbidity 11 years later. Another study reported that male South Korean manufacturing employees who reported high levels of work-related stress were more likely to catch the common cold over the next several months than were those employees who reported lower work-related stress levels (Park et al. Later, you 522 Chapter 14 Stress, Lifestyle, and Health will explore the mechanisms through which stress can produce physical illness and disease. In general, stressors can be placed into one of two broad categories: chronic and acute. Chronic stressors include events that persist over an extended period of time, such as caring for a parent with dementia, long-term unemployment, or imprisonment. Acute stressors involve brief focal events that sometimes continue to be experienced as overwhelming well after the event has ended, such as falling on an icy sidewalk and breaking your leg (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007). They can include major traumatic events, significant life changes, daily hassles, as well as other situations in which a person is regularly exposed to threat, challenge, or danger. Stressors in this category include exposure to military combat, threatened or actual physical assaults. Many potential stressors we face involve events or situations that require us to make changes in our ongoing lives and require time as we adjust to those changes. Examples include death of a close family member, marriage, divorce, and moving (Figure 14.

Based on what you have learned about child development and social roles knee pain treatment running discount rizact 10mg online, why do you think boys and girls display different types of bullying behavior Bullying involves three parties: the bully pain treatment for plantar fasciitis cheap rizact 10 mg mastercard, the victim knee pain treatment by physiotherapy discount rizact 5 mg on-line, and witnesses or bystanders pain medication dogs can take order rizact 10 mg amex. The act of bullying involves an imbalance of power with the bully holding more power-physically pain treatment for labor rizact 10mg for sale, emotionally pain treatment guidelines pdf buy generic rizact 10mg online, and/or socially over the victim. The experience of bullying can be positive for the bully, who may enjoy a boost to self-esteem. However, there are several negative consequences of bullying for the victim, and also for the bystanders. Bullies may be attracted to children who get upset easily because the bully can quickly get an emotional reaction from them. Children who are overweight, cognitively impaired, or racially or ethnically different from their peer group may be at higher risk. Cyberbullying With the rapid growth of technology, and widely available mobile technology and social networking media, a new form of bullying has emerged: cyberbullying (Hoff & Mitchell, 2009). Cyberbullying, like bullying, is repeated behavior that is intended to cause psychological or emotional harm to another person. What is unique about cyberbullying is that it is typically covert, concealed, done in private, and the bully can remain anonymous. This anonymity gives the bully power, and the victim may feel helpless, unable to escape the harassment, and unable to retaliate (Spears, Slee, Owens, & Johnson, 2009). Cyberbullying can take many forms, including harassing a victim by spreading rumors, creating a website defaming the victim, and ignoring, insulting, laughing at, or teasing the victim (Spears et al. In cyberbullying, it is more common for girls to be the bullies and victims because cyberbullying is nonphysical and is a less direct form of bullying (Figure 12. Interestingly, girls who become cyberbullies often have been the victims of cyberbullying at one time (Vandebosch & Van Cleemput, 2009). The effects of cyberbullying are just as harmful as traditional bullying and include the victim feeling frustration, anger, sadness, helplessness, powerlessness, and fear. Victims will also experience lower self-esteem (Hoff & Mitchell, 2009; Spears et al. Furthermore, recent research suggests that both cyberbullying victims and perpetrators are more likely to experience suicidal ideation, and they are more likely to attempt suicide than individuals who have no experience with cyberbullying (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010). What features of technology make cyberbullying easier and perhaps more accessible to young adults What can parents, teachers, and social networking websites, like Facebook, do to prevent cyberbullying The bystander effect is a phenomenon in which a witness or bystander does not volunteer to help a victim or person in distress. Social psychologists hold that we make these decisions based on the social situation, not our own personality variables. The impetus behind the bystander effect was the murder of a young woman named Kitty Genovese in 1964. The story of her tragic death took on a life of its own when it was reported that none of her neighbors helped her or called the police when she was being attacked. However, Kassin (2017) noted that her killer was apprehended due to neighbors who called the police when they saw him committing a burglary days later. Not only did bystanders indeed intervene in her murder (one man who shouted at the killer, a woman who said she called the police, and a friend who comforted her in her last moments), but other bystanders intervened in the capture of the murderer. Social psychologists claim that diffusion of responsibility is the likely explanation. Diffusion of responsibility is the tendency for no one in a group to help because the responsibility to help is spread throughout the group (Bandura, 1999). Because there were many witnesses to the attack on Genovese, as evidenced by the number of lit apartment windows in the building, individuals assumed someone else must have already called the police. The responsibility to call the police was diffused across the number of witnesses to the crime. Have you ever passed an accident on the freeway and assumed that a victim or certainly another motorist has already reported the accident In general, the greater the number of bystanders, the less likely any one person will help. Researchers have documented several features of the situation that influence whether we form relationships with others. There are also universal traits that humans find attractive in 456 Chapter 12 Social Psychology others. In this section we discuss conditions that make forming relationships more likely, what we look for in friendships and romantic relationships, the different types of love, and a theory explaining how our relationships are formed, maintained, and terminated. Voluntary behavior with the intent to help other people is called prosocial behavior. Is personal benefit such as feeling good about oneself the only reason people help one another In fact, people acting in altruistic ways may disregard the personal costs associated with helping (Figure 12. For example, news accounts of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York reported an employee in the first tower helped his co-workers make it to the exit stairwell. After helping a co-worker to safety he went back in the burning building to help additional co-workers. In this case the costs of helping were great, and the hero lost his life in the destruction (Stewart, 2002). An empathetic person makes an emotional connection with others and feels compelled to help (Batson, 1991). Other researchers argue that altruism is a form of selfless helping that is not motivated by benefits or feeling good about oneself. Certainly, after helping, people feel good about themselves, but some researchers argue that this is a consequence of altruism, not a cause. Other researchers argue that helping is always self-serving because our egos are involved, and we receive benefits from helping (Cialdini, Brown, Lewis, Luce, & Neuberg 1997). It is challenging to determine experimentally the true motivation for helping, whether is it largely self-serving (egoism) or selfless (altruism). You might be surprised to learn that the answer is simple: the people with whom you have the most contact. For example, there are decades of research that shows that you are more likely to become friends with people who live in your dorm, your apartment building, or your immediate neighborhood than with people who live farther away (Festinger, Schachler, & Back, 1950). It is simply easier to form relationships with people you see often because you have the opportunity to get to know them. We are more likely to become friends or lovers with someone who is similar to us in background, attitudes, and lifestyle. Sharing things in common will certainly make it easy to get along with others and form connections. When you and another person share similar music taste, hobbies, food preferences, and so on, deciding what to do with your time together might be easy. Homophily is the tendency for people to form social networks, including friendships, marriage, business relationships, and many other types of relationships, with others who are similar (McPherson et al. This can be quite obvious in a ceremony such as a wedding, and more subtle (but no less significant) in the day-to-day workings of a relationship. By forming relationships only with people who are similar to us, we will have homogenous groups and will not be exposed to different points of view. In other words, because we are likely to spend time with those who are most like ourselves, we will have limited exposure to those who are different than ourselves, including people of different races, ethnicities, social-economic status, and life situations. Self-disclosure is the sharing of personal information (Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998). We form more intimate connections with people with whom we disclose important information about ourselves. Indeed, self-disclosure is a characteristic of healthy intimate relationships, as long as the information disclosed is consistent with our own views (Cozby, 1973). People differ in what they consider attractive, and attractiveness is culturally influenced. Research, however, suggests that some universally attractive features in women include large eyes, high cheekbones, a narrow jaw line, a slender build (Buss, 1989), and a lower waistto-hip ratio (Singh, 1993). For men, attractive traits include being tall, having broad shoulders, and a narrow waist (Buss, 1989). Both men and women with high levels of facial and body symmetry are generally considered more attractive than asymmetric individuals (Fink, Neave, Manning, & Grammer, 2006; Penton-Voak et al. Social traits that people find attractive in potential female mates include warmth, affection, and social skills; in males, the attractive traits include achievement, leadership qualities, and job skills (Regan & Berscheid, 1997). Although humans want mates who are physically attractive, this does not mean that we look for the most attractive person possible. In fact, this observation has led some to propose what is known as the matching hypothesis which asserts that people tend to pick someone they view as their equal in physical attractiveness and social desirability (Taylor, Fiore, Mendelsohn, & Cheshire, 2011). For example, you and most people you know likely would say that a very attractive movie star is out of your league. So, even if you had proximity to that person, you likely would not ask them out on a date because you believe you likely would be rejected. If you think you are particularly unattractive (even if you are not), you likely will seek partners that are fairly unattractive (that is, unattractive in physical appearance or in behavior). Robert Sternberg (1986) proposed that there are three components of love: intimacy, passion, and commitment. Commitment is standing by the person-the "in sickness and health" part of the relationship. However, different aspects of love might be more prevalent at different life stages. Other forms of love include liking, which is defined as having intimacy but no passion or commitment. Companionate love, which is characteristic of close friendships and family relationships, consists of intimacy and commitment but no passion. Finally, fatuous love is defined by having passion and commitment, but no intimacy, such as a long term sexual love affair. Can you describe other examples of relationships that fit these different types of love Typically, only those relationships in which the benefits outweigh the costs will be maintained. People are motivated to maximize the benefits of social exchanges, or relationships, and minimize the costs. People prefer to have more benefits than costs, or to have nearly equal costs and benefits, but most 460 Chapter 12 Social Psychology people are dissatisfied if their social exchanges create more costs than benefits. If you have ever decided to commit to a romantic relationship, you probably considered the advantages and disadvantages of your decision. You may have considered having companionship, intimacy, and passion, but also being comfortable with a person you know well. You may think that over time boredom from being with only one person may set in; moreover, it may be expensive to share activities such as attending movies and going to dinner. Psychologists categorize the causes of human behavior as those due to internal factors, such as personality, or those due to external factors, such as cultural and other social influences. Lay people tend to over-rely on dispositional explanations for behavior and ignore the power of situational influences, a perspective called the fundamental attribution error. People from individualistic cultures are more likely to display this bias versus people from collectivistic cultures. In order to know how to act in a given situation, we have shared cultural knowledge of how to behave depending on our role in society. Social norms dictate the behavior that is appropriate or inappropriate for each role. Each social role has scripts that help humans learn the sequence of appropriate behaviors in a given setting. The famous Stanford prison experiment is an example of how the power of the situation can dictate the social roles, norms, and scripts we follow in a given situation, even if this behavior is contrary to our typical behavior. Our attitudes and beliefs are influenced not only by external forces, but also by internal influences that we control. An internal form of attitude change is cognitive dissonance or the tension we experience when our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are in conflict. In order to reduce dissonance, individuals can change their behavior, attitudes, or cognitions, or add a new cognition. External forces of persuasion include advertising; the features of advertising that influence our behaviors include the source, message, and audience. The central route to persuasion uses facts and information to persuade potential consumers. The peripheral route uses positive association with cues such as beauty, fame, and positive emotions. Conformity to group norms is driven by two motivations, the desire to fit in and be liked and the desire to be accurate and gain information from the group. Authority figures also have influence over our behaviors, and many people become obedient and follow orders even if the orders are contrary to their personal values. Conformity to group pressures can also result in groupthink, or the faulty decision-making process that results from cohesive group members trying to maintain group harmony. Group situations can improve human behavior through facilitating performance on easy tasks, but inhibiting performance on difficult tasks. The presence of others can also lead to social loafing when individual efforts cannot be evaluated. Prejudice, or negative feelings and evaluations, is common when people are from a different social group.

Griffin and Broniarczyk (2007) find that this quest for the ideal product can lead consumers to continue searching for products even when it has diminishing returns on satisfaction pain treatment mayo clinic best 5 mg rizact. In an Internet search task pain management for osteosarcoma in dogs purchase rizact 10mg amex, subjects searched more when options were nonalignable than alignable pain solutions treatment center hiram ga purchase rizact 5 mg with mastercard. These findings suggest that consumers may self-create large assortments of attractive options chronic pain treatment vancouver cheap rizact 5mg visa, and as a result pain treatment sciatica quality 5mg rizact, self-inflict negative decision-making consequences pain medication for dog injury quality 10 mg rizact. In summary, choice likelihood was shown to decrease as assortment size increased, particularly if the assortment was differentiated on nonalignable and complementary attributes. Three causal mechanisms of higher cognitive load, increased product expectations, and higher regret were shown to underlie the higher levels of choice avoidance associated with increasing assortments differentiated on nonalignable and complementary attributes. These findings are troublesome as the very attribute types (nonalignable, complementary) that positively impact assortment perceptions are the cause of subsequent choice difficulty. However, one could envision instances where complementary attributes have common, alignable levels. Preference Development Consumer knowledge may also be helpful in offsetting the higher cognitive loads and increased product expectations of large assortments. A choice task though requires more than a mere knowledge of product attributes and product alternatives. In order to make a choice, the key is that consumers have developed preferences regarding attribute levels and formulated trade-offs on the relative importance of these attributes. Consumers with well-developed preferences have been shown to have an easier time processing large assortments, higher levels of satisfaction, and higher likelihood of choice from large assortments (Huff man & Kahn, 1998; Chernev, 2003a, 2003b). In their study of consumer choice from large assortments, Huffman and Kahn (1998) examined the effects of preference development by varying three levels of a learning manipulation that occurred prior to choice. Specifically, they manipulated whether consumers had: (1) attribute knowledge where subjects were exposed to all attributes and attribute levels, (2) attribute preference where subjects expressed preference for attribute levels, or (3) attribute importance where subjects first rated relative importance between attributes and then expressed with-in attribute preferences. Study 1 of Huff man and Kahn (1998) compared knowledge of attributes versus preferences for attributes (#1 vs. Their results showed that subjects who had expressed attribute preferences perceived the choice set as less complex than consumers who merely had knowledge of the attributes. However, the learning manipulation of attribute knowledge versus attribute preference had no effect on the percentage of consumers who expressed a readiness to make a choice or satisfaction with choice. A second study compared the two higher preference development levels of attribute preference versus attribute importance (#2 vs. Their results showed that subjects in the attribute preference condition perceived the choice set as less complex, were more satisfied with their chosen alternative, and more likely to believe they had made optimal choice than subjects in the attribute importance condition. That is, subjects who had expressed their attribute preferences had a more positive experience choosing from a large assortment than did subjects with more well-developed preferences that had also expressed relative attribute importance. This finding is likely attributable to the learning manipulation task being onerous for attribute importance subjects (trade-offs on 25 attributes) and their dissatisfaction carrying over to their later assortment choice. Thus, Huff man and Kahn (1998) recommend that if one is trying to assist novice consumers in choosing from a large assortment that developing attribute preferences strikes the correct balance between not being overwhelming in the learning phase and assisting in the product choice phase. Chernev (2003a, 2003b) also posits that making a product choice from an assortment is a twostage process of first deciding an ideal attribute combination and then locating the product in the assortment that best matches this ideal. He fi nds that consumers with well-developed preferences have an easier time choosing from assortments as their ideal product is already constructed. In Chernev (2003a), subjects were asked to choose a product from either a small assortment containing 4 options or a large assortment containing 16 options (the 4 options from the small set and 12 additional options). Comparable to the attribute preference learning manipulation in Huffman and Kahn (1998), half of his subjects articulated their attribute preferences and half of subjects were simply exposed to the attribute information prior to choice (#2 vs. His results showed that more subjects elected to choose a product from the large instead of the small assortment when they had articulated their preferences (96%) than when they had just received attribute information (72%). Thus, having more developed preferences increased the likelihood of consumers choosing a product from a large assortment. It is notable though that the majority of subjects in both conditions elected to choose from the large compared to small assortment set. Furthermore, subjects who had articulated their preferences examined only about half as many piece of information as subjects who only had attribute knowledge (13. In contrast, subjects who had not articulated their preferences engaged in more attribute-based processing as they needed to complete the initial stage of determining their ideal product from the large assortment display prior to proceeding to second stage of product choice. Chernev (2003b) found that for large assortments, subjects had a lower propensity to switch their choice when preferences were articulated (13% switching) than when they were not articulated (38% switching). An opposite pattern was observed for small assortments whereby subjects who had articulated preferences had a higher propensity to switch from choice (27%) compared to subjects who had not formed their preferences (9% switching). For consumers with well-developed preferences, a large assortment increases the probability of finding a match with their ideal and thus they are less inclined to switch. However, these same consumers will not fare as well in finding a close match to their ideal in the small assortment set, and thus are more likely to switch. In conclusion, having well-developed preferences facilitates consumers choosing from large assortments. Consumers who have well-developed preferences encounter less decision difficulty, are more likely to choose from large assortments, and have both stronger preferences for and are more confident in their chosen alternative than consumers who do not possess well-developed preferences. Maximizer-Satisficer Individual difference variables will also affect how consumers deal with the challenge of choosing a product from a large assortment. Satisficers, on the other hand, have the goal of choosing a product that is good enough to meet their standards for acceptability. The first factor captures the extent to which an individual is on the look out for better options. The second factor captures the extent to which an individual struggles to pick the best product. The third factor captures the extent to which an individual has high standards. In a series of studies, Schwartz and colleagues demonstrated that maximizers compared to satisficers have significantly lower levels of life satisfaction, happiness, optimism, and self-esteem and significantly higher levels of regret and depression. Additionally, maximizers were shown to engage in more product comparisons, social comparisons, and counterfactual comparisons but feel less satisfied with their decision. The higher incidence of comparisons and counterfactuals contributes to higher levels of product regret. In the pursuit of obtaining the best product, maximizers have been found to achieve higher task performance but do worse subjectively than satisficers. Iyengar, Wells, and Schwartz (2006) compared the job search process of university graduates who were categorized on the basis of Schwartz et al. Their research showed that maximizers obtained jobs with 20% higher starting salaries than satisficers. However, maximizers were less satisfied with the jobs they obtained and experienced greater negative affect through the job search process than satisficers. Of particular relevance for assortment, they found that an increase in the number of options considered was associated with a steeper decrease in outcome satisfaction for maximizers compared to satisficers. That is, maximizers searched more job options, but the more options the searched, the less satisfied they were with their final option. Thus, maximizers have a more difficult time selecting from a broad product assortment than satisficers. Maximizers are more likely to engage in compensatory processing and be overwhelmed with the cognitive load of large assortments. Conversely, satisficers are more likely to engage in non-compensatory processing to find an acceptable alternative that meets their minimal attribute cut-offs. As maximizers engage in more exhaustive product searches and consider more options, their product ideal becomes less obtainable in a single product than the ideal of a satisficer, and consequently they are less satisfied with their product choice. As assortment size increases, maximizers relative to satisficers are more likely to experience higher levels of regret due to their propensity to engage in social comparison and counterfactual reasoning. Consumer assortment perceptions are shown to extend beyond the number of products offered and also be affected by the composition of products in the assortment, heuristic cues, and the format in which products are presented. Therefore, a smaller product set that is properly composed and organized can lead to higher assortment perceptions than a larger product set as well as facilitate choice. However, assortment perceptions are not one-to-one function of # of products offered. Smaller product sets may be perceived as offering greater assortment than larger product sets. Two individual consumer factors were then shown to be capable of mitigating these negative decisionmaking consequences. Consumers with well-developed relative to less-developed preferences were shown to have less difficulty processing large assortments, higher levels of satisfaction with the choice process, higher incidence of choosing a large compared to small assortment, and greater preference with their chosen option. Secondly, consumers with exhibited satisficer relative to maximizer tendencies were shown to be less susceptible to the negative psychological consequences of large assortments experiencing higher satisfaction with the choice process and lower regret with product choice. Next we discuss some new directions being explored in assortment research, the effects of assortment on consumption and well-being. Extending this research, Kahn and Wansink (2004) found that perceived assortment mediates the effect of actual assortment on consumption. As previously discussed, Kahn and Wansink (2004) showed that consumer perceptions of assortment are influenced by information structure variables. Specifically, they demonstrated that increasing the number of options increased perceived assortment more for organized and asymmetric assortment structures. In Study 2, subjects were ostensibly recruited for a study on television advertising and offered either 6 or 24 jelly bean options while they waited. The assortment structure varied whether the display was randomly disorganized or organized by flavor and color. Their results showed that as the assortment size increased from 6 to 24 options, consumption quantity increased for organized assortments (from 12. Increases in perceived assortment led subjects to anticipate higher enjoyment of the items to be consumed and this desire led them to consume greater quantities. When assortment size was made salient, subjects appeared to use the size of the assortment as consumption norm to gauge how many items to consume. Providing corroborating evidence in an experimental financial setting, Morrin, Imman, and Broniarczyk (2007) find that increases in the number of mutual funds offered in 401(k) plans led to increases in the number of funds investors placed in their investment portfolios. The consequences of product assortments on consumer well-being is a topic of growing commentary. Kahn and Wansink (2004) suggest that health practitioners should be particularly cognizant of the effects of assortment size and structure on consumption in the mounting battle with obesity. Schwartz (2000, 2004) wonders if exploding product assortments are related to the rising depression rates in the United States. Although assortments offer the lure of control over product choice, the decision difficulty, lower satisfaction, and higher regret associated with choice from assortments may make the ultimate lack of control self-evident and contribute to depression. Choice from a large assortment may also have a detrimental impact on subsequent consumer choices and behavior. Baumeister and Vohs (2003) demonstrate how product choice is ego-depleting and the energy expended in a current choice may leave a consumer with less willpower for a subsequent task. As choosing from large assortments is taxing, particularly for maximizers, this research suggests that maximizers may have less self-control for a subsequent product task. This self-focus may diminish the quality of subsequent other-focused activities such as later social interactions and altruistic behavior. In sum, initial evidence exists that broad assortments increase product consumption and thought-provoking reflections ponder their psychic toll. Consumers find large assortments attractive for their process-related benefits of stimulation, choice freedom, and informative value and for their choice-related benefits of higher ideal product availability, ability to satisfy multiple needs in a single location, potential for variety-seeking, and flexibility for uncertain future preferences. Large relative to small assortments are associated with higher cognitive loads, difficult trade-offs, small differences in relative option attractiveness, and more foregone options upon choice. Consequently, large assortments were shown to lead to a greater incidence of failure to obtain the best product, dissatisfaction with the choice process and chosen product, higher regret with the chosen product, and a higher likelihood of choice avoidant behavior. A key question is to what extent consumers recognize the downsides of large assortments for later choice. Even when product choice was made salient, the majority of subjects were shown to still be drawn to larger relative to smaller assortments (Chernev, 2006). The multi-dimensional nature of consumer assortment perceptions indicate that consumers have some implicit recognition of the dual tension between the attractiveness of assortments and subsequent difficulty of choosing a product from within the assortment. The cognitive dimension of assortment perceptions appears to capture the attractiveness of assortments being positively related to the number of unique options and size of assortment display. The affective dimension of consumer assortment perceptions appears to recognize the difficulty of choosing from large assortments being positively related to ease of shopping, ease of locating a favorite product, and congruency with shopping goals. The pinnacle of assortment research is discovering how marketers can keep the gain and reduce the pain associated with choosing from large assortments. Research on consumer assortment perceptions suggests that product sets that are selectively comprised of favorite and unique products and appropriately organized and displayed can lead a choice set containing fewer products to be perceived as offering greater assortment than another choice set containing more products and simultaneously facilitate consumer choice. Limiting the number of products though may prove difficult in product categories where consumer preferences are heterogeneous. In such cases, retailers should be cognizant that increasing product sets by adding options differentiated on nonalignable and complementary attributes will prove particularly taxing for consumer choice and may lead to lower choice incidence, particularly for consumers with ill-defined preferences and maximizer tendencies. Choosing from large assortments was shown to be easier if the assortments were differentiated on alignable or noncomplementary attributes and consumers possessed well-developed preferences or were willing to satisfice their product choice. Research Challenges Designing experiments to compare the effect of a small versus large number of product options would appear to be a straightforward task. However, there are a number of complexities that an assortment researcher needs to appreciate. First, one needs to determine the number of options that constitutes a small versus large assortment. As evidence suggests that having 10 or more options alters the complexity of the choice task (Maholtra, 1982), one might argue that 10 or more options constitutes a large assortment. Moreover, such an argument assumes that there is a threshold above which assortments become difficult to process without any further effects of additional increases in the number of options. A serious limitation of assortment research is that much of it has been conducted comparing only two levels of option size. Future assortment research should consider manipulating at least three option size levels to rule out calibration issues and to test for non-linear effects.

Syndromes

Source attributions and persuasion: Perceived honesty as a determinant of message scrutiny pain treatment for bladder infection buy rizact 5 mg without a prescription. The gradual threshold model of ambivalence: Relating the positive and negative bases of attitudes to subjective ambivalence chronic pain treatment uk proven rizact 10 mg. Extending the bases of subjective attitudinal ambivalence: Interpersonal and intrapersonal antecedents of evaluative tension pain treatment hepatitis c buy 5mg rizact with amex. Understanding implicit and explicit attitude change: A systems of reasoning analysis fibromyalgia treatment guidelines pain buy rizact 10mg low cost. Predicting the effectiveness of different strategies of advertising variation: A test of the repetition-variation hypotheses who cancer pain treatment guidelines purchase rizact 10 mg without prescription. The social-identity function in person perception: Communicated meanings of product preferences pain medication for dogs for arthritis order 5 mg rizact amex. Source credibility and attitude certainty: A meta-cognitive analysis of resistance to persuasion. Measures and manipulations of strength related properties of attitudes: Current practice and future directions. Self-schema matching and attitude change: Situational and dispositional determinants of message elaboration. Rather than entering a choice situation as a "blank slate" and assessing alternatives completely on-the-spot, individuals virtually always have some knowledge of the type or category of product in question and often about specific brands as well. This chapter will consider how concepts like brands and categories of products can be related to other representations in memory and the implications for consumer behavior. We begin with the assumption that these consumer-related concepts can be uniquely represented in memory and associated to varying degrees with other mental representations. This variation, the strength of the association between two representations, determines the likelihood that activating one concept will result in the activation of the associated concept. Obviously, the nature of the associates of, for example, the representation of a brand will largely determine how an individual thinks about that brand and whether they might choose to purchase it. A representation strongly associated with a brand is more likely than a representation weakly associated with a brand to ultimately influence behavior. Predicting consumer choice thus entails having some idea about both the content of associated representations and on the strength of those associations. Many different kinds of associations in memory may prove relevant to consumer behavior. A brand, for instance, might be associated with usage situations, particular attributes, previous experiences, and so on. We will focus on two kinds of associated representation: attitudes, which can be conceptualized as associations between an object and a summary evaluation of that object, and category-exemplar associations, associations between an object and a superordinate classification. The chapter will present some broad guidelines for identifying situations and product classes for which each type of association is likely to be particularly relevant. We will fi rst focus on the determinants and consequences of attitudinal associative strength. We then will turn to category-exemplar associations, and then finally we will discuss some contextual factors that moderate the role of associative strength in consumer choice situations. When individuals encounter or consider an attitude object, the associated evaluation can be activated. Since the proposal of this theoretical perspective, considerable research has examined the consequences, determinants, and correlates of attitude accessibility and its role in the attitude-to-behavior process (see Fazio, 1995, for a review). This section will review these findings with attention to the implications for how attitudes function in object-appraisal and decision-making processes of interest to consumer psychology. Before proceeding, it will be useful to clarify what is intended when describing attitudes as object-evaluation associations in memory that vary in strength. Individuals may not only store evaluations of physical objects, but also of concepts of all levels of abstraction. These evaluations associated with objects have various bases that range from "hot" affective responses to "cold" analytical beliefs concerning attributes of the object. Regardless of the precise nature of the object and evaluation, the strength of the association between the two will influence the likelihood of its use. Th is structural approach to attitude strength and to attitudes in general has the advantage of operating at an information processing level of analysis, allowing for specificity in the treatment of the concept and integration thereof into broader models of cognition and behavior. Accessibility the crux of the conceptualization of attitudes as object-evaluation associations is that the strength of this association influences attitude accessibility, the likelihood that the attitude will be activated from memory automatically when the object is encountered. According to associative network theories of mental representation, associations in memory will be strengthened to the extent that the representations they link are experienced or thought about together; this strength changes only slowly over time (Smith & Queller, 2001). Attitude accessibility can be measured by the latency of response to a direct attitudinal inquiry. Relatively high accessibility may be chronic, reflecting high associative strength, or it may be temporarily enhanced by recency of use (Higgins, 1996). Empirical support regarding the automatic activation of attitudes was gathered using priming procedures (Fazio, Sanbonmatsu, Powell, & Kardes, 1986). The evidence concerns the effect of semantic primes on the latency with which individuals are able to identify the connotation of target adjectives. These primes were positive or negative words selected idiosyncratically for each participant. Priming with these items, which were presented to participants as distracting "memory words," facilitated performance in the adjective connotation task when the valence of the primed object was the same as the valence of the target adjective. On the other hand, when the valence of the prime and target were incongruent, it took longer to identify the target adjective as positive or negative. So, participants were able to classify a positive adjective more quickly when it was preceded by a positively valued object. Importantly, the facilitation and inhibition effects of the primes were more pronounced for objects towards which participants held accessible attitudes. Similar automatic attitude activation has been demonstrated in research employing brand names as primes (Sanbonmatsu & Fazio, 1986). Accessible attitudes towards brand names influenced how quickly individuals could categorize the target adjectives that followed them as positive or negative. A notable characteristic of the priming procedure is that accessible attitudes towards the prime words influenced evaluative categorization even though participants were aware that the prime itself was irrelevant to their goals in the task, providing preliminary evidence that the influence of the primes was spontaneous and uncontrollable. Further evidence of the validity of automatic attitude activation is that it also occurs when participants are engaged in a task that is not dependent on any evaluative intent. The findings regarding the moderating role of associative strength on automatic attitude activation relate to an important conceptual distinction offered by Converse (1970). Based on the finding that attitude accessibility varies as a function of associative strength, it has been suggested that the distinction between attitudes and nonattitudes may be more usefully considered a continuum (Fazio, Sanbonmatsu, Powell, & Kardes, 1986). At the nonattitude end of the continuum is the case in which no appropriate a priori evaluation is available in memory and evaluative assessment must occur in an on-line fashion. Approaching the upper end of the continuum, well-learned object-evaluation associations are increasingly capable of being activated automatically from memory. Attitudes that are low in accessibility may also be activated, but this is more likely to require motivated efforts to retrieve information about the attitude-object. The potential for automatic activation provides much of the functional value of attitudes. Accessible attitudes can be activated instantly upon encountering an attitude-object and help individuals understand and react to the world around them. The basic value of attitudes is this object-appraisal function (Smith, Bruner, & White, 1956) and automatic activation allows the rapid initiation of approach or avoidance behavior based on these object-appraisals. The following sections will discuss the consequences of attitude accessibility, which determines the functional role of attitudes in guiding thought and behavior. Manipulating Associative Strength A number of manipulations have been used to increase the strength of the association between attitude-objects and evaluations (thus increasing attitude accessibility) in the laboratory. Always, participants are one way or another induced to note and rehearse their attitudes by repeatedly expressing them. For instance, this has been achieved by requesting that participants copy their attitudinal ratings onto multiple forms (Fazio et al. Another variation of this manipulation has the advantage of distinguishing the effects of attitude accessibility from mere object accessibility. In these experiments, each attitude-object was presented an equivalent number of times, but how often the attitude-object was paired with an evaluative question versus some control question. Increasing attitudinal associative strength through repeated expression increases automatic attitude activation, measured by the extent to which that attitude-object facilitates the evaluative categorization of items of congruent valence and inhibits the evaluative categorization of items of incongruent valence (Fazio et al. As we describe the ways in which attitudes ultimately exert an influence on behavior in the following sections, it should be remembered that such effects should only be expected when object-evaluation associations are sufficiently strong, either due to a manipulation of associative strength or the pre-existing strength of associations held by individuals. In subsequent sections, we will explore other consequences of the associative strength of attitudes-ones that serve as further mechanisms through which attitudes ultimately shape behavior. Perception Higher-order cognitive and motivational processes can influence perception in a top-down fashion. For example, it has been demonstrated that individuals perceive a briefly presented ambiguous figure (it could be construed as either the letter "B" or the number "13") in the manner consistent with their desired outcome (Balcetis & Dunning, 2006). Participants were informed that a number or letter would appear on a computer screen, indicating into which experimental condition they would be assigned. Participants were more likely to perceive the stimulus in a way that would indicate that they would be in the condition requiring that they drink orange juice rather than a disgusting, viscous "health drink. For example, Changizi and Hall (2001) found that when individuals were thirsty, they displayed a greater tendency to perceive a concept associated with water, transparency, in ambiguous visual stimuli varying in opacity. Research by Powell and Fazio (summarized in Fazio, Roskos-Ewoldsen, & Powell, 1994) examined the influence of attitudinal biases on perception in an informationally sparse visual environment. Participants were required to observe a computerized tennis game in which flashes of light appeared in a rectangle divided by a vertical line, representing a tennis court. The flashes of light represented the location of shots landed by either the computer or (supposedly) a confederate who had previously behaved in such a way that he/she would be liked or disliked by the participant. The opposite pattern of results was observed when participants had been led to dislike the confederate. Attention An important aspect of the influence of associative strength on basic perceptual processes is the potential for objects associated with highly accessible attitudes to attract visual attention when the object enters the visual field. Roskos-Ewoldsen and Fazio (1992) assessed recall for stimulus items presented briefly in groups of six in a circular visual array. Participants were more likely to notice and report objects for which they held more accessible attitudes. This was the case both when attitude accessibility had been previously measured by latency of response and when it was manipulated through attitude rehearsal. In another experiment in the series, participants noticed the more attitude-evoking objects incidentally, i. In a fi nal experiment, performance on a visual search task was shown to be disrupted by the presence of more attitude-evoking objects as distractors. Attitude accessibility predicted the extent to which these distracters interfered with performance on the visual search task. Thus, the influence of attitude accessibility on selective attention appears to be automatic not only in that it is spontaneous, but also in that it occurs regardless of intentional efforts to ignore the attitude-object. Roskos-Ewoldsen and Fazio (1992) argued that attitudes provide an adaptive, orienting function towards objects that have hedonic value, allowing them to be rapidly approached or avoided. Indeed, in environments such as supermarkets, many objects are specifically designed to attract attention and are intended to compete in this respect with one another. One strategy to ensure that a product draws attention is through manipulating properties of the object itself, usually by carefully designing its appearance. Categorization All objects are multiply categorizable and the particular category or categories activated depend not only on properties of the object, but also on those of the observer. Another consequence of the associative strength of an attitude is its capacity to determine which of multiple suitable categories is actually applied to the object (Smith, Fazio, & Cejka, 1996). For instance, at any moment in time a given individual might construe a cup of yogurt as a "snack" or as a "dairy product. This associative strength makes the category more attitude-evoking, more likely to attract attention, and, hence, more likely to dominate construal of the yogurt. That is, the individual is more likely to categorize yogurt as a dairy product than a snack. An attitude rehearsal manipulation increased the accessibility of attitudes toward one of two potential categorizations for each item in a series of objects. When these objects were later presented as a cue, the category for which attitudes had been rendered more accessible was more likely to be evoked. In addition, individuals could more quickly verify that the category applied to the object. Thus, accessible attitudes shape basic categorization processes and facilitate construals that are hedonically meaningful. Information Processing Relatedly, yet another well-known consequence of attitudes is their potential to shape the manner in which individuals interpret information. As a function of their personal biases, individuals may view and describe the same event in radically different ways. In a classic experiment, Lord, Ross, and Lepper (1979) found that individuals who held strong opinions toward the death penalty examined relevant empirical evidence in a biased manner. College students who either supported or opposed capital punishment were exposed to two fabricated studies, one that seemingly provided evidence supporting the efficacy of the death penalty as a deterrent to crime and one that denied it. Participants rated not the conclusions but the actual methodology of the studies as being more valid when the study reached conclusions consistent with their own attitudes. Participants actually endorsed their initial opinions more strongly after reading the conflicting accounts, even though the quality of the messages themselves was essentially equal. Houston and Fazio (1989) examined the influence of attitude accessibility on such information processing. Because the participants in the research by Lord and colleagues (1979) were selected on the basis of their strong pre-existing attitudes toward the topic, Houston and Fazio reasoned that these participants likely had highly accessible attitudes toward capital punishment and that the biased processing effect might be less general and not occur for participants who did not have such accessible attitudes-an attitude will not bias processing if it is not activated. Attitude accessibility was measured in one study via latency of response to a direct attitudinal query and experimentally manipulated via repeated attitudinal expression in another. In both cases, the strength of the object-evaluation association predicted the degree of correspondence between attitudes toward capital punishment and ratings of the scientific quality of the studies.

Buy rizact 5 mg fast delivery. Bowen: Alternative Therapy for Pain.

References