|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

"Cheap 100 mg januvia overnight delivery, diabetes test machine price in india".

N. Dudley, M.B.A., M.D.

Co-Director, Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine

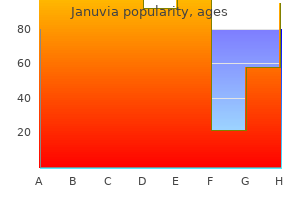

Several factors metabolic joint disease discount januvia 100mg fast delivery, some mentioned above in regard to deterioration of gait blood glucose below 70 purchase 100mg januvia otc, are responsible for the inordinately high rate of falling among older persons diabetes type 1 mortality buy discount januvia 100 mg. Impairment of visual function and particularly of vestibular function with normal aging are important contributors diabetic ketoacidosis in dogs discount 100mg januvia with amex. In a group of 34 elderly patients who were free of neurologic disease, postural hypotension, and leg deformities, Weiner and colleagues found a moderate or severe degree of postural reflex impairment in two-thirds. The failure to make rapid postural adjustments, which is a product of aging alone, accounts for the occurrence of falls in the course of usual activities such as walking, changing position, or descending stairs. Postural hypotension, often due to antihypertensive agents and the use of sedative drugs, is another important cause of falling in the elderly (page 464). Of course, falling is an even more prominent feature of certain age-related neurologic diseases: stroke, Parkinson disease, normalpressure hydrocephalus, and progressive supranuclear palsy, among others. Other Restricted Motor Abnormalities in the Aged these are too numerous to be more than catalogued. They reflect the many Effects of Aging on Stance and Gait and Related Motor Impairments (See also Chap. Motor agility actually begins to decline in early adult life, even by the 30th year; it seems related to a gradual decrease in neuromuscular control as well as to changes in joints and other structures. The reality of this motor decrement is best appreciated by professional athletes who retire at age 35 or thereabout because their legs give out and cannot be restored to their maximal condition by training. They cannot run as well as younger athletes, even though the strength and coordination of their arms is relatively preserved. More subtle and imperceptibly evolving changes in stance and gait are ubiquitous features of aging (Chap. Gradually the steps shorten, walking becomes slower, and there is a tendency to stoop. Compulsive, repetitive movements are the most frequent: mouthing movements, stereotyped grimacing, protrusion of the tongue, side-to-side or toand-fro tremor of the head, odd vocalizations such as sniffing, snorting, and bleating. In some respects these disorders resemble tics (quasivoluntary movements to relieve tension), but careful observation shows that they are not really voluntary. Haloperidol and other drugs of this class have an unpredictable therapeutic effect, seeming at times to benefit the patient only by the superimposition of a drug-induced rigidity. Old age is thought always to carry a liability to tremulousness, and indeed, one sees this association with some frequency. The head, chin, or hands tremble and the voice quavers, yet there is not the usual slowness and poverty of movement, facial impassivity, or flexed posture that would stamp the condition as parkinsonian. Some instances of tremor are clearly familial, having appeared or worsened only late in life. Charcot, in a review of over 2000 elderly inhabitants of the Salpetriere, could find only about ^ ` 30 with tremor. Some cases probably represent the exaggeration or emergence of essential tremor, but many cases cannot be explained on this basis. Spastic or spasmodic dysphonia, a disorder of middle and late life characterized by spasm of all the throat muscles on attempted speech, is discussed on page 428. Blepharoclonus or blepharospasm, an involuntary movement of the eyelids, is also described on page 93. Morphologic and Physiologic Changes in the Aging Nervous System these have never been fully established. From the third decade of life to the beginning of the tenth decade, the average decline in weight of the male brain is from 1394 to 1161 g, a loss of 233 g. The pace of this change, very gradual at first, accelerates during the sixth or seventh decades. The loss of brain weight, which correlates roughly with enlargement of the lateral ventricles and widening of the sulci, is presumably the result of neuronal degeneration and replacement gliosis, although this has not been proved. The counting of cerebrocortical neurons is fraught with technical difficulties, even with the use of computer-assisted automated techniques (see the critical review of neuron-counting studies by Coleman and Flood). Most studies, point to a depletion of the neuronal population in the neocortex, especially evident in the seventh, eighth, and ninth decades. Cell loss in the limbic system (hippocampus, parahippocampal and cingulate gyri) is of special interest in regard to memory. Ball, who measured the neuronal loss in the hippocampus, recorded a linear decrease of 27 percent between 45 and 95 years of age. These changes seem to proceed without relationship to Alzheimer neurofibrillary changes and senile plaques (Kemper).

Table 57-1 Depression secondary to neurologic diabetes symptoms skin problems generic 100mg januvia amex, medical diabetes mellitus definition cdc buy generic januvia 100 mg on line, and surgical diseases and drugs 1 diabetes type 1 unconscious januvia 100mg sale. Neuronal degenerations-Alzheimer diabetic videos purchase januvia 100 mg free shipping, Huntington, frontotemporal dementia, Lewy-body disease, Parkinson disease, and multiple system atrophy b. Analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents (other than steroids)-indomethacin, phenacetin d. Antibiotics, particularly cycloserine, ethionamide, griseofulvin, isoniazid, nalidixic acid, and sulfonamide f. Antihypertensive drugs-clonidine, propranolol (and certain other beta-adrenergic blockers) g. Reactive Depressions and Depressions with Medical and Neurologic Diseases Patients reacting to a medical or neurologic illness seldom express feelings of sadness or despair without mentioning physical concomitants, such as easy fatigability, anxiety, tension headaches, dizziness, loss of appetite, reduced interest in life and love, trouble in falling asleep, or premature awakening. It follows that whenever these symptoms become manifest in the course of medical disease, they should arouse suspicion of a depressive reaction (Table 57-1). The pain may be based on an attendant disease but is prolonged, disabling, sometimes vague in nature, and recalcitrant to straightforward medical and surgical approaches. All patients with chronic pain syndromes should be evaluated psychiatrically, as pointed out in Chap. In a number of major medical illnesses, depressive symptoms occur with such frequency as to become almost part of the disease. Contrariwise, in certain chronic, occult diseases, symptoms such as lassitude and fatigue may resemble and be mistaken for a depressive reaction. Hypothyroidism, infectious mononucleosis, infectious hepatitis, carcinoma of the pancreas, lymphoma, myeloma, metastatic carcinoma, malnutrition, polymyalgia rheumatica, and frontal lobe tumors, especially meningiomas, may simulate depression for weeks or months before the diagnosis becomes evident. Sedative drugs, beta-adrenergic blocking agents, beta-interferon, and the phenothiazines may evoke a depressive reaction; corticosteroids can induce a peculiar psychiatric state in which confusion, insomnia, and either an elevation of mood or depression are combined. A depressed mood may also emerge during the tapering-off period of steroid medication or during their initial use (a hypomanic state is more common). Of particular significance is the reactive depression that occurs on learning of a serious medical or neurologic disease. Often such an emotional reaction, which the physician may tend to ignore, is the dominant manifestation of a disease that threatens the life pattern and independence of the patient. Recognition by the patient that he has suffered a stroke or that she has cancer, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Parkinson disease is almost always followed by some degree of reactive depression, often with an element of anxiety. A prime example is the depression that follows myocardial infarction (Wishnie et al). Once the patient is home, fatigability that approaches exhaustion is the main complaint and interferes with accustomed activities. Symptoms of irritability, anxiety, and despondency are next in order of frequency, followed by insomnia and feelings of aimlessness and boredom. Although most of these patients ul- timately recover without medical assistance the depression exacts a high toll in terms of mental suffering. Some studies have indicated that patients with left anterior cerebral lesions, involving predominantly the lateral frontal cortex or basal ganglia (as detected by computed tomography scanning) and examined within several weeks of the stroke, have a greater frequency and severity of depression than do patients with lesions in other locations (Starkstein et al; Robinson). According to these authors, lesions of the right hemisphere do not show this correlation with depression but do show a higher association with pathologic cheerfulness or mania. Our colleagues Levine and Finkelstein have reported the occurrence of psychotic depression with hallucinations and delusions in patients with right temporoparietal infarcts. Our own experience suggests a not surprising relationship between the degree of motor and language disability and the severity of poststroke depression but a less predictable relationship to the location of the lesion. The possible predisposing effects of minor previous episodes of depression, family history of depressive illness, and medications have not been studied systematically. With regard to emotional reactions in degenerative brain diseases, Parkinson disease is complicated by a depressive reaction in approximately one quarter of cases. Weakness and fatigability, the principal psychologic manifestations, are added to the bradykinesia, and the resulting therapeutic problem becomes formidable. Another hazard in Parkinson and in Lewy body disease is the tendency for L-dopa itself to provoke a depression in a limited number of patients, sometimes with suicidal tendencies, paranoid ideation, and psychotic episodes. Huntington chorea is quite often associated with depression, even before the movement disorder and dementia become conspicuous. In one series, 10 of 101 patients with Huntington disease either committed suicide or attempted it. Also, Alzheimer disease may be accompanied by depressive symptoms, in which instance it is difficult or impossible early in the illness to evaluate the relative contributions of the mood disorder and the dementia.

It is differentiated from Huntington disease by onset before age 5 zyrtec type 1 diabetes generic januvia 100mg with mastercard, progressing little and having no associated mental deterioration (Breedveld et al) diabetes symptoms gas order januvia 100 mg online. Other progressive neurologic disorders inherited as autosomal dominant traits and beginning in adolescence or adult life diabetes symptoms double vision order januvia 100 mg line. There are several other rare degenerative disorders with chorea diabetes type 1 eating plan cheap januvia 100mg line, some of which have already been mentioned. A midlife progressive chorea without dementia (after more than 25 years follow- Figure 39-4. The bulge in the inferolateral border of the lateral ventricle, normally created by the head of the caudate nucleus (lower scan from a patient of the same age for comparison), has been obliterated. Viewed from the molecular perspective, the pathogenesis of this disease is a direct but still poorly understood consequence of the aforementioned expansion of the polyglutamine region of huntingtin (the protein product of the Huntington gene). It has been shown that the expansion predisposes the mutant huntingtin protein to aggregate in the nuclei of neurons. Moreover, the protein accumulates preferentially in cells of the striatum and parts of the cortex affected in Huntington disease. In at least one family in which this clinical picture is dominantly inherited, the fundamental defect is a mutation in the gene encoding the light chain (L chain) of ferritin (Curtis). Affected individuals have axonal changes in the pallidum with swollen, ubiquitin- and tau-positive aggregates; serum ferritin levels may be depressed. The implication of this mutation is that perturbations of iron metabolism may be toxic to neurons, a feature that also characterizes Hallervorden-Spatz disease (page 832). Other problems in differential diagnosis include bilateral thalamic degeneration with dementia and chorea, referred to earlier; paroxysmal choreoathetosis (page 68); Wilson disease (page 830); acquired hepatocerebral degeneration (page 975); and, most often and especially, tardive dyskinesia (page 94). Many drugs in addition to the toxic effects of L-dopa and antipsychotic medications occasionally cause chorea (amphetamines, cocaine, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, isoniazid). Treatment the dopamine antagonist haloperidol, in daily doses of 2 to 10 mg, is probably the most effective agent in suppressing the movement disorder. Because of the danger of superimposing tardive dyskinesia on the chronic disorder, the chorea should be treated only if it is functionally disabling, using the smallest possible dosages. Haloperidol may also help alleviate abnormalities of behavior or emotional lability, but it does not alter the progress of the disease. The authors have not been impressed with the therapeutic effectiveness of other currently available drugs. Levodopa and other dopamine agonists make the chorea worse and, in the rigid form of the disease, evoke chorea. Drugs that deplete dopamine or block dopamine receptors- such as reserpine, clozapine, and tetrabenazine- suppress the chorea to some degree, but their side effects (drowsiness, akathisia, and tardive dyskinesia) outweigh their desired effects. The juvenile (rigid) form of the disease is probably best treated with antiparkinsonian drugs. Preliminary studies of the transplantation of fetal ganglionic tissue into the striatum achieved mixed results. The psychologic and social consequences of the disease require supportive therapy, and genetic counseling is essential. Huntington disease pursues a steadily progressive course and death occurs as mentioned, on average 15 to 20 years after onset, sometimes much earlier or later. The acanthocytosis, according to Sakai and coworkers, is due to an abnormal composition of covalently (tightly) bound fatty acids in erythrocyte membrane proteins (palmitic and docosahexanoic acids increased and stearic acid decreased). Although the inheritance is usually autosomal recessive, at least one family with the dominantly transmitted trait has been described. The acanthocytosis may be overlooked when it is mild but can be detected by scanning electron microscopy. In the series of 19 cases reported by Hardie and colleagues, the manifestations included dystonia, tics, vocalizations, rigidity, and lip and tongue biting; more than half had cognitive impairment or psychiatric features. The disease has been linked in almost all families to chromosome 9q, where there is a mutation in the gene encoding a large (3100 amino acid) protein designated chorein that is thought to be involved in cellular protein sorting and trafficking (Rampoldi). Some of the families with dominantly inherited neuroacanthocytosis have mutations in the chorein gene.

Experimental work in monkeys and limited data from patients suggest that improvement can be obtained by restraining the normal limb and forcing use of the sound limb blood sugar 80 generic januvia 100mg. Speech and language therapy are particularly valuable in identifying the risk of aspiration as noted above diabetes mellitus y xerostomia order januvia 100mg with amex. Specific therapy should be given in appropriate cases diabetic candy januvia 100mg with mastercard, and certainly improves the morale of the patient and family diabete x insulina cheap januvia 100 mg free shipping. Preventive Measures Since the primary objective in the treatment of atherothrombotic disease is prevention, efforts to control the risk factors must continue. The carotid vessels, being readily accessible, must always be examined for the presence of a bruit; the latter quite reliably indicates a stenosis, though not all stenoses cause a bruit and some bruits heard bilaterally are transmitted sounds from a stenotic aortic valve. Other instances are attributable to raised intracranial pressure (pseudotumor cerebri). The management of patients with asymptomatic carotid bruits has been considered above. For patients who have had a stroke from atherothrombotic disease and are functional, preventive measures consist of reducing the future occurrence of strokes. Such measures include the following: (1) aspirin- which has been shown to reduce the risk of second stroke slightly, but its effect, as already noted, should not be overestimated (see page 697); (2) any required antihypertensive agents- whether given therapeutically or for diagnostic procedures, should be administered with caution; (3) cholesterol-lowering drugs should be administered unless the cholesterol level is already low or there is a contraindication; (4) smoking cessation is mandatory and the patient should be supported in such efforts; and (5) particular care should be taken to maintain the systemic blood pressure, oxygenation, and intracranial blood flow during general surgical procedures, especially in elderly patients. In most cases of cerebral embolism, the embolic material consists of a fragment that has broken away from a thrombus within the heart. Somewhat less frequently the source is intra-arterial, from the distal end of a thrombus within the lumen of an occluded or severely stenotic carotid or vertebral artery or the distal end of a carotid dissection, or possibly from an atheromatous plaque that has ulcerated into the lumen of the carotid sinus. Single or sequential emboli may also arise from large atheromatous plaques in the ascending aorta. Thrombotic or infected material (endocarditis) that adhere to the aortic or mitral heart valves and break away are also well appreciated sources of embolism. Embolism due to fat, tumor cells (atrial myxoma), fibrocartilage, amniotic fluid, or air seldom enters into the differential diagnosis of stroke except in special circumstances. The embolus usually becomes arrested at a bifurcation or other site of natural narrowing of the lumen of an intracranial vessel, and ischemic infarction follows. The infarction is pale, hemorrhagic, or mixed; hemorrhagic infarction nearly always indicates embolism, though most are pale. Any region of the brain may be affected, the territory of the middle cerebral artery, particularly the superior division, being the most frequently involved. Large embolic clots can block large vessels (sometimes the carotids in the neck or at their termination intracranially), while tiny fragments may reach vessels as small as 0. The embolic material may remain arrested and plug the lumen solidly, but more often it breaks into fragments that enter smaller vessels and disappear, so that even careful pathologic examination fails to reveal their final location. Because of the rapidity with which embolic occlusion develops, there is not much time for collateral influx to become established. Thus, sparing of the territory distal to the site of occlusion is not as evident as in thrombosis. However, the vascular anatomy and ischemia-modifying factors mentioned above, under "The Ischemic Stroke," are still operative and influence the size and magnitude of the infarct. Brain embolism is predominantly a manifestation of heart disease, and fully 75 percent of cardiogenic emboli lodge in the brain. The commonest identifiable cause is chronic or recent atrial fibrillation, the source of the embolus being a mural thrombus within the atrial appendage (Table 34-7). Patients with chronic atrial fibrillation are about six times more liable to stroke than an agematched population with normal cardiac rhythm (Wolf et al) and the risk is considerably higher if there is also rheumatic valvular disease as mentioned earlier. Furthermore, the risk conferred by the presence of atrial fibrillation varies with age, being 1 percent per year in persons younger than 65, and as high as 8 percent per year in those over 75 with additional risk factors. These levels of risk are of prime importance in determining the advisability of anticoagulation, as discussed below. Mural thrombus deposited on the damaged endocardium overlying a myocardial infarct in the left ventricle, particularly if there is an aneurysmal sac, is an important source of cerebral emboli, as is a thrombus associated with severe mitral stenosis without atrial fibrillation. Emboli tend to occur in the first few weeks after an acute myocardial infarction, but Loh and colleagues found that a lesser degree of risk persists for up to 5 years. Cardiac catheterization or surgery, especially valvuloplasty, may disseminate fragments from a thrombus or a calcified valve. Another source of embolism is the carotid or vertebral artery, where clot forming on an ulcerated atheromatous plaque may be detached and carried to an intracranial branch (artery-to-artery embolism).