|

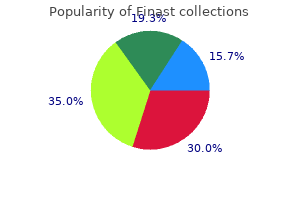

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Marilyn L. Yucaitis, RNBA, CEN, TNCCP,

However german hair loss cure generic finast 5 mg visa, insufficient information has been accumulated on these drugs hair loss cure found order 5 mg finast free shipping, and there fore they are not recommended for use in clini cal patient settings hair loss from wen purchase finast 5 mg without a prescription. Their use in alcohol with drawal should be considered experimental and premature for the present hair loss cure how long order 5mg finast with visa. Early proper medical management of alcohol withdrawal reduces the probability of these complications hair loss 3 months after giving birth buy 5 mg finast with mastercard, assuming early recognition hair loss naturally home remedies order finast 5 mg line. Patients with severe withdrawal symp toms, multiple past detoxifications (more than three), and cooccurring unstable medical and psychiatric conditions should be managed simi larly. Once an initial clinical screening and assess ment have been made, and the diagnosis is rea sonably certain, medication should be given. Giving the patient a benzodiazepine should not be delayed by waiting for the return of labora tory studies, transportation problems, or the availability of a hospital bed. Correction of fluids and electrolytes (salts in the blood), hyperthermia (high fever), and hypertension are vital. The physician should consider intramus cular or intravenous haloperidol (Haldol and others) to treat agitation and hallucinations. Nursing care is vital, with particular attention to medication administration, patient comfort, soft restraints, and frequent contact with ori enting responses and clarification of environ mental misperceptions. The majority of alcohol withdrawal seizures occur within the first 48 hours after cessation or reduction of alcohol, with peak incidence around 24 hours (Victor and Adams 1953). Most alcohol withdrawal seizures are singular, but if more than one occurs they tend to be within several hours of each other. While alcohol withdrawal seizures can occur several days out, a higher index of suspicion for other causes is prudent. The occurrence of an alcohol withdrawal seizure happens quickly, usually without warn ing to the individual experiencing the seizure or anyone around him. The patient loses con sciousness, and if seated usually slumps over, but if standing will immediately fall to the floor. This part of the seizure is called the tonic phase, which usually lasts for a few seconds and rarely more than a minute. The next part of the seizure (more dramatic and generally remembered by witnesses) con 64 sists of jerking of head, neck, arms, and legs. Immediately after the jerking ceases, the patient generally has a period of what appears to be sleep with more regular breathing. Rarely, the patient may appear not to waken at all and have a second period of rigidity followed by muscle jerking. Upon awakening, the individual usually is mildly confused as to what has happened and may be disoriented as to where she or he is. This period of postseizure confusion generally lasts only for a few minutes but may persist for several hours in some patients. Headache, sleepiness, nausea, and sore muscles may per sist in some individuals for a few hours. Patients who start to retch or vomit should be gently placed on their side so that the vomitus (stomach contents vomited) may exit the mouth and not be taken into the lungs. Predicting who will have a seizure during alco hol withdrawal cannot be accomplished with any great certainty. There are some factors that clearly increase the risk of a seizure, but even in individuals with all of these factors, most patients will not have a seizure. Out of 100 people experiencing alcohol withdrawal only two or three of them will have a seizure. The best single predictor of a future alcohol withdrawal seizure is a previous alcohol with drawal seizure. Individuals who have had three or more documented withdrawal episodes in the past are much more likely to have a seizure regardless of other factors including age, gen der, or overall medical health. Such attempts at object insertion may cause damage to the teeth and tongue, or objects may get partially swallowed and obstruct the airway. Vomitus taken into the lungs is a severe medical condition leading to immediate difficulty breathing and, within hours, severe pneumonia. In the rare patient with recurrent multiple seizures or status epilepticus (continuous seizures of sever al minutes) an anesthesiology consultation may be required for general anesthesia. Despite this report, the consensus panel agrees that hospi talization for further detoxification treatment is strongly advised to monitor and ameliorate other withdrawal symptoms, reduce suffering, and stabilize the patient for rehabilitation treatment. Further evaluation of a first seizure often warrants neurologic evaluation (com puterized tomography and electroencephalo gram), even if the seizure may be suspected to have been due to alcohol withdrawal. Patient Care and Comfort Interpersonal support and hygienic care along with adequate nutrition should be provided. Staff assisting patients in detoxification should provide whatever assistance is necessary to help get patients cleaned up after entering the facility and bathed thoroughly as soon as they have been medically stabilized. Attention to the treatment of scabies, body lice, and other skin conditions should be given. The patient should be screened for physical trauma, including bruises and lacerations. Patients with an altered mental status or altered level of con sciousness should be seen in emergency depart ments, evaluated, and possibly hospitalized. Staff should continue to observe patients for head injuries after admission because some head injuries, such as subdural hematomas, may not immediately be evident and cost con siderations may preclude obtaining a brain scan in some settings. Antidiabetic agents in concert with alcohol may produce hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) and lactic acidosis (blood that has become too acidic). The therapeutic efficacy and margin of safety for the use of antianxiety medications, antidepressants, and antipsychotic medication is thought by some to be lessened by alcohol use, but this is based largely on anecdotal information. Alcohol interacts with numerous other classes of medications that lead to less serious results. Some important examples are sedatives, tranquilizers, antiseizure medica tions, and anticoagulants (blood thinners) such as Coumadin. Patients who may be taking such medications need to be carefully observed and have their medications carefully monitored. Opioids Opioids are highly addicting, and their chronic use leads to withdrawal symptoms that, although not medically dangerous, can be high ly unpleasant and produce intense discomfort. Opioid agonists stimulate these receptors and opioid antagonists block them, preventing their action. Some examples include benzodiazepines, barbi turates, meprobamate, and other sedative hyp notic groups. A disulfi ramlike (Antabuse) reaction characterized by flushing, sweating, tachycardia, nausea, and chest pain has been reported for metronidazole and several antibiotics including, but not limit ed to , cefamandole, cefoperazone, and cefote tan. Acetaminophen in low doses may act acutely with alcohol to produce hepatotoxicity (liver damage). Clinicians also should deter 66 Opioid Withdrawal Symptoms All opioid agents produce similar withdrawal signs and symptoms with some variance in severity, time of onset, and duration of symp tomatology, depending on the agent used, the duration of use, the daily dose, and the interval between doses. For instance, heroin withdrawal typically begins 8 to 12 hours after the last heroin dose and subsides within a period of 3 to 5 days. Methadone withdrawal typically begins 36 to 48 hours after the last dose, peaks Chapter 4 after about 3 days, and gradually subsides over a period of 3 weeks or longer. Physiological, genetic, and psychological factors can signifi cantly affect intoxication and withdrawal sever ity. Figure 44 summarizes many of the com mon signs and symptoms of opioid intoxication and withdrawal. The clinician uses intoxication and withdraw al measures as guides to avoid under or over medicating patients during medically super vised detoxification; the number and intensity of signs determine the severity of opioid with drawal. It is important to appreciate that untreated opioid withdrawal gradually builds in severity of signs and symptoms and then diminishes in a selflimited manner. Repeated assessments should be made during detoxifi cation to determine whether symptoms are improving or worsening. Repeated assess ments also should address the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions. Detoxification strategies should aim to establish control over the opioid withdrawal syndrome, after which dose reductions can be made gradually. Medical complications associated with opioid withdrawal can develop and should be quick ly identified and treated. Unlike alcohol and sedative withdrawal, uncomplicated opioid withdrawal is not lifethreatening. Rarely, severe gastrointestinal symptoms produced by opioid withdrawal, such as vomiting or diar rhea, can lead to dehydration or electrolyte imbalance. Most individuals can be treated with oral fluids, especially fluids containing electrolytes, and some might require intra venous therapies. In addition, underlying cardiac illness could be made worse in the presence of the autonomic arousal (increased blood pressure, increased pulse, sweating) that is characteristic of opioid withdrawal. Fever may be present during opioid with drawal and typically will respond to detoxifi cation. Other causes of fever should be evalu ated, particularly with intravenous users, Figure 44 Signs and Symptoms of Opioid Intoxication and Withdrawal Opioid Intoxication Signs Bradycardia (slow pulse) Hypotension (low blood pressure) Hypothermia (low body temperature) Sedation Meiosis (pinpoint pupils) Hypokinesis (slowed movement) Slurred speech Head nodding Symptoms Euphoria Analgesia (painkilling effects) Calmness Opioid Withdrawal Signs Tachycardia (fast pulse) Hypertension (high blood pressure) Hyperthermia (high body temperature) Insomnia Mydriasis (enlarged pupils) Hyperreflexia (abnormally heightened reflexes) Diaphoresis (sweating) Piloerection (gooseflesh) Increased respiratory rate Lacrimation (tearing), yawning Rhinorrhea (runny nose) Muscle spasms Symptoms Abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea Bone and muscle pain Anxiety Source: Consensus Panelist Charles Dackis, M. Finally, any condition buprenorphine, involving pain is likely to worsen has been during opioid with drawal because of a approved for use. Management of Withdrawal With Medications the management of opioid withdrawal with medications is most commonly achieved through the use of methadone (in addition to adjunctive medications for nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach cramps). Federal regu lations restrict the use of methadone for opioid withdrawal to specially licensed programs, except in cases where the patient is hospitalized for treatment of another acute medical condi tion. However, since clonidine detox ification is less effective against many opioid withdrawal symptoms, adjunctive medicines often are necessary to treat insomnia, muscle pain, bone pain, and headache. Adjunctive agents should not be used in the place of an adequate detoxification dosage. Offlabel use (prescribing an agent approved for another condition) could be difficult to justify, given the efficacy of methadone in reversing opioid withdrawal. Detoxification is indicated for treatmentseek ing persons who display signs and symptoms sufficient to warrant treatment with medica tions and for whom maintenance is declined or for some reason is not indicated or practi cal. In addition, individuals dependent on opioids sometimes are hospitalized for other health problems and may require hospital based detoxification even though they are not Management of Withdrawal Without Medications It is not recommended that clinicians attempt to manage significant opioid withdrawal symp toms (causing discomfort and lasting several hours) without the effective detoxification agents discussed below. Even mild levels of opi oid use commonly produce uncomfortable lev els of withdrawal symptomatology. Management of this syndrome without medica tions can produce needless suffering in a popu lation that tends to have limited tolerance for physical pain. Such patients also can be maintained on methadone during the course of hospitalization for any condition other than opioid addiction. The hospital does not have to be a registered opi oid treatment program, as long as the patient was admitted for a detoxification treatment for some substance other than opioids. On the other hand, some persons may not have used sufficient amounts of opioids to develop withdrawal symptoms, and for others suffi cient time may have elapsed since their last dose to extinguish withdrawal and eliminate the need for detoxification. This is one of many impor tant reasons to consider conversion to mainte nance during most methadone detoxification admissions. Once the dose requirement for methadone has been established, methadone can be given once daily and generally tapered over 3 to 5 days in 5 to 10mg daily reductions. Clinicians should take care not to underdose patients with methadone; adequate dosage is vitally important. Patients some times exaggerate their daily consumption to receive greater dosages of methadone. For this reason, history is no substitute for a physical examination that screens for signs of opioid withdrawal. Treating clinicians should not only be familiar with the intoxication and withdrawal signs that are set forth in Figure 44 (p. Avoidance of overmedicating is crucial during methadone detoxification because excessive doses of this agent can produce overdose, whereas opioid withdrawal does not constitute a medical danger in otherwise healthy adults. Patients with significant opioid dependence may require a starting dose of 30 to 40mg per day; this dose range should be adequate for even the most severe withdrawal. If the degree of dependence is unclear, withdrawal signs and symptoms can be reassessed 1 to 2 hours after giving a dose of 10mg of methadone. The practice of giving a dose of methadone and later assessing its effect (also termed a challenge dose) is an important intervention of detoxification. Sedation or intoxication signs after a methadone challenge dose indicate a lower starting dose. Similarly, intoxication at any point of the detoxification 69 Methadone this section discusses methadone as an agent for detoxification. The regulations also specify that if a patient has failed two detoxification attempts in a 12month period he or she must be evaluated for a different course of treat ment. Methadone is a longacting agonist at the:opi oid receptor site that, in effect, displaces hero in (or other abused opioids) and restabilizes the site, thereby reversing opioid withdrawal symp toms. If maintained for long enough, this stabi lizing effect can even reverse the immunologic Physical Detoxification Services for Withdrawal From Specific Substances signals the need to hold or more rapidly wean (reduce to a zero dose) the methadone. Care should be taken to avoid giving methadone to newly admitted patients with signs of opioid intoxication, since overdose could result. Note that methadone stabilization is the treat ment of choice for patients who are pregnant and opioid dependent. Completion rates for opioid detoxification using clonidine have been low (ranging from 20 to 40 per cent); those patients who complete the proce dure are more likely to be dependent on opi oids other than heroin, have private health insurance, and report lower levels of subjec tive withdrawal symptoms than those who do not complete (Strobbe et al. These parameters can be relaxed to 80/50 in some cases if the patient continues to complain of withdrawal and is not experiencing symptoms of orthostatic hypotension (a sudden drop in blood pressure caused by standing). Clonidine detoxification is best con ducted in an inpatient setting, as vital signs and side effects can be monitored more close ly in this environment. In cases of severe withdrawal, a standing dose (given at regular intervals rather than purely "as needed") of clonidine might be advantageous (Alling 1992).

Rescuers must balance patient needs with patient safety and safety for the responders 2 hair loss 9 year old finast 5mg lowest price. Rapid descent by a minimum of 500-1000 feet is a priority hair loss nutritional deficiency purchase finast 5mg online, however rapidity of descent must be balanced by current environmental conditions and other safety considerations Notes/Educational Pearls Key Considerations 1 hair loss medication side effects generic finast 5 mg free shipping. Patients suffering from altitude illness have exposed themselves to a dangerous environment hair loss cure replicel discount 5 mg finast free shipping. By entering the same environment hair loss blogs cheap finast 5mg with mastercard, providers are exposing themselves to the same altitude exposure hair loss in men experiencing purchase finast 5mg overnight delivery. Descent of 500-1000 feet is often enough to see improvements in patient conditions 3. Consider airway management needs in the patient with severe alteration in mental status 2. Wilderness Medical Society consensus guidelines for the prevention and treatment of acute altitude illness. Wilderness Medical Society Practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of acute altitude illness: 2014 update. Revision Date September 8, 2017 Updated November 23, 2020 306 Conducted Electrical Weapon Injury. Manage the condition that triggered the application of the conducted electrical weapon with special attention to patients meeting criterion for excited delirium [see Agitated or Violent Patient/Behavioral Emergency guideline] 2. Make sure patient is appropriately secured or restrained with assistance of law enforcement to protect the patient and staff [see Agitated or Violent Patient/Behavioral Emergency guideline] 3. Perform comprehensive trauma and medical assessment as patients who have received conducted electrical weapon may have already been involved in physical confrontation 4. If discharged from a distance, two single barbed darts (13mm length) should be located a. Do not remove barbed dart from sensitive areas (head, neck, hands, feet or genitals) Patient Presentation Inclusion Criteria 1. Patient received either the direct contact discharge or the distance two barbed dart discharge of the conducted electrical weapon 2. Patient may be under the influence of toxic substances and or may have underlying medical or psychiatric disorder Exclusion Criteria No recommendations Patient Management Assessment 1. Evaluate patient for evidence of excited delirium manifested by varied combination of agitation, reduced pain sensitivity, elevated temperature, persistent struggling, or hallucinosis Treatment and Interventions 1. Make sure patient is appropriately secured with assistance of law enforcement to protect the patient and staff. Consider psychologic management medications if patient struggling against physical devices and may harm themselves or others 2. Treat medical and traumatic injury Updated November 23, 2020 307 Patient Safety Considerations 1. Before removal of the barbed dart, make sure the cartridge has been removed from the conducted electrical weapon 2. Patient should not be restrained in the prone, face down, or hog-tied position as respiratory compromise is a significant risk 3. The patient may have underlying pathology before being tased (refer to appropriate guidelines for managing the underlying medical/traumatic pathology) 4. Perform a comprehensive assessment with special attention looking for to signs and symptoms that may indicate agitated delirium 5. Transport the patient to the hospital if they have concerning signs or symptoms 6. Drive Stun is a direct weapon two-point contact which is designed to generate pain and not incapacitate the subject. Only local muscle groups are stimulated with the Drive Stun technique Pertinent Assessment Findings 1. Thoroughly assess the tased patient for trauma as the patient may have fallen from standing or higher 2. Acidosis and catecholamine evaluation following simulated law enforcement ``use of force' encounters. Revision Date September 8, 2017 Updated November 23, 2020 309 Electrical Injuries Aliases Electrical burns, electrocution Patient Care Goals 1. Assess primary survey with specific focus on dysrhythmias or cardiac arrest - apply a cardiac monitor 3. Assess for potential associated trauma and note if the patient was thrown from contact point - if patient has altered mental status, assume trauma was involved and treat accordingly 5. Assess for potential compartment syndrome from significant extremity tissue damage 6. Administer fluid resuscitation per burn protocol - remember that external appearance will underestimate the degree of tissue injury Updated November 23, 2020 310 6. Electrical injuries may be associated with significant pain, treat per Pain Management guideline 7. Electrical injury patients should be taken to a burn center whenever possible since these injuries can involve considerable tissue damage 8. When there is significant associated trauma this takes priority, if local trauma resources and burn resources are not in the same facility Patient Safety Considerations 1. Move patient to shelter if electrical storm activity still in area Notes/Educational Pearls Key Considerations 1. Direct tissue damage, altering cell membrane resting potential, and eliciting tetany in skeletal and/or cardiac muscles b. Conversion of electrical energy into thermal energy, causing massive tissue destruction and coagulative necrosis c. Mechanical injury with direct trauma resulting from falls or violent muscle contraction 2. Both types of current can cause involuntary muscle contractions that do not allow the victim to let go of the electrical source iv. However, strong involuntary reactions to shocks in this range may lead to injuries. Revision Date September 8, 2017 Updated November 23, 2020 313 Lightning/Lightning Strike Injury Aliases Lightning burn Patient Care Goals 1. Initiate immediate resuscitation of cardiac arrest victim(s), within limits of mass casualty care, also known as "reverse triage" 4. Golf courses, exposed mountains or ledges and farms/fields all present conditions that increase risk of lightning strike, when hazardous meteorological conditions exist 2. Lacking bystander observations or history, it is not always immediately apparent that patient has been the victim of a lightning strike Subtle findings such as injury patterns might suggest lightning injury Inclusion Criteria Patients of all ages who have been the victim of lightning strike injury Exclusion Criteria No recommendations Patient Management Assessment 1. Assure patent airway - if in respiratory arrest only, manage airway as appropriate 2. Consider early pain management for burns or associated traumatic injury [see Pain Management guideline] Patient Safety Considerations 1. Victims do not carry or discharge a current, so the patient is safe to touch and treat Notes/Educational Pearls Key Considerations 1. Lightning strike cardiopulmonary arrest patients have a high rate of successful resuscitation, if initiated early, in contrast to general cardiac arrest statistics 2. If multiple victims, cardiac arrest patients whose injury was witnessed or thought to be recent should be treated first and aggressively (reverse from traditional triage practices) a. Patients suffering cardiac arrest from lightning strike initially suffer a combined cardiac and respiratory arrest b. Patients may be successfully resuscitated if provided proper cardiac and respiratory support, highlighting the value of "reverse triage" 4. It may not be immediately apparent that the patient is a lightning strike victim 5. Injury pattern and secondary physical exam findings may be key in identifying patient as a victim of lightning strike 6. Investigating a possible new injury mechanism to determine the cause of injuries related to close lightning flashes. Mountain medical mystery: unwitnessed death of a healthy young man, caused by lightning. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of lightning injuries. The lightning heart: a case report and brief review of the cardiovascular complications of lightning injury. Inner ear damage following electric current and lightning injury: a literature review. Injuries, sequelae, and treatment of lightning-induced injuries: 10 years of experience at a Swiss trauma center. Immediate cardiac arrest and subsequent development of cardiogenic shock caused by lightning strike. Author, Reviewer and Staff Information Authors Co-Principal Investigators Carol A. This guideline defines minimum standards and inclusions used and referenced throughout this document under the "Quality Improvement" section of each guideline 3. Exclusion Criteria None Toolkit for Key Categories of Data Elements Incident Demographics 1. This information will always apply and be available, even if the responding unit never arrives on scene (is cancelled) or never makes patient contact b. Many systems do not require use of these fields as they can be time-consuming to enter, often too detailed. However, there is some utility in targeted use of these fields for certain situations such as stroke, spinal exams, and trauma without needing to enter all the fields in each record. Many additional factors must be considered when determining capacity including the situation, patient medical history, medical conditions, and consultation with direct medical oversight. Trauma/Injury the exam fields have many useful values for documenting trauma (deformity, bleeding, burns, etc. Use of targeted documentation of injured areas can be helpful, particularly in cases of more serious trauma. Because of the endless possible variations where this could be used, specific fields will not be defined here. Note, however that the exam fields use a specific and useful Pertinent Negative called "Exam Finding Not Present. Additional Vitals Options All should have a value in the Vitals Date/Time Group and can be documented individually or as an add-on to basic, standard, or full vitals a. Signs and Symptoms should support the provider impressions, treatment guidelines and overall care given. A symptom is something the patient experiences and tells the provider; it is subjective. Provider impressions should be supported by symptoms but not be the symptoms except on rare occasions where they may be the same. This patient would have possible Symptoms of altered mental status, unconscious, respiratory distress, and respiratory failure/apnea. This impression will specifically define the call as an overdose with opiates, rather than a case where one of the symptoms was also used as an impression when the use of naloxone and other assessments and diagnostic tools could not determine an etiology for the symptom(s). The narrative summarizes the incident history and care in a manner that is easily digested between caregivers. Specifically, this would include the detailed history of the scene, what the patient may have done or said or other aspects of thecal that only the provider saw, heard, or did. Most training programs provide limited instruction on how to properly document operational and clinical processes, and almost no practice. Most providers learn this skill on the job, and often proficient mentors are sparse. Some more experienced providers use it as they find telling the story from start to finish works best to organize their thoughts. A drawback to this method is that it is easy to forget to include facts because of the lack of structure. It minimizes the likelihood of forgetting information and ensures documentation is consistent between records and providers. Updated November 23, 2020 335 Medications Given Showing Positive Action Using Pertinent Negatives For medications that are required by protocol. If a patient had the intended therapeutic response to the medication, but a side effect that caused a clinical deterioration in another body system, then "Improved" should be chosen and the side effects documented as a complication. The patient condition deteriorated or continued to deteriorate because either the medication: i. Was the wrong medication for the clinical situation and the therapeutic effect caused the condition to worsen. Not Applicable: the nature of the procedure has no direct expected clinical response. An effective procedure that caused an improvement in the patient condition may also have resulted in a procedure complication and the complication should be documented Updated November 23, 2020 336. In the case of worsening condition, documentation of the procedure complications may also be appropriate. Currently there are three versions of the data standard available for documentation and in which data is stored: a. These fields require real data and do not accept Nil (Blank) values, Not Values, or Pertinent Negatives. However, required fields allow Nil (blank) values, Not Values, or Pertinent Negatives to be entered and submitted. Values can be left blank, which can either be an accidental or purposeful omission of data.

Cheap 5 mg finast. Hair Growth using Castor Oil (90 day challenge).

In vitro proliferative responses to some soluble antigens hair loss post pregnancy finast 5mg generic, but not mitogens hair loss cure 91 cheap finast 5mg without a prescription, have been shown to correlate with in vivo delayed hypersensitivity hair loss before and after discount finast 5mg visa. The role hair loss cure za proven finast 5mg, however hair loss normal buy finast 5 mg line, of lymphocyte proliferation as measured in vitro in the pathogenesis of the delayed-type hypersensitivity tissue reaction is unclear hair loss cure 65 buy cheap finast 5mg line. Chemokines are small (8 to 10 kDa) proteins secreted by many immune and nonimmune cells with essential roles in inflammatory and immune reactions, including the late-phase cutaneous response. The inflammatory consequences induced by immune functions may be detected by nonspecific tests, such as a complete blood cell count with differential, sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and other acute-phase reactants. Autoantibody profiles offer important diagnostic adjuncts in the diagnosis of collagen vascular diseases, vasculitides, and cytotoxicity disorders. A well-designed skin test and laboratory ordering form should provide useful information to the ordering physician, his/her staff, health care providers, and other physicians who may be consulted in the future. The clinical significance of a single fungus test reagent may be difficult to ascertain because of important confounders, such as sampling method, culture conditions, nonculturable species, allergenic differences between spores, and hyphae and preferential ecologic niches. For clinical purposes, molds are often characterized as outdoor (Alternaria and Cladosporium species), indoor (Aspergillus and Penicillium species), or both (Alternaria, Aspergillus, and Penicillium species). A whole-body extract is the only currently available diagnostic reagent for fire ant sting allergy. Major inhalant acarid and insect allergens include several species of house dust mite and cockroach. Although commercial skin tests for drugs, biologics, and chemicals are not available, specialized medical centers prepare and use such tests under appropriate clinical situations. More than 300 low- and highmolecular-weight occupational allergens have been identified. As previously emphasized, knowledge of specific patterns of cross-reactivity among tree, grass, and weed pollens is essential in preparing an efficient panel of test reagents. The skin prick/puncture test is superior to intracutaneous testing for predicting nasal allergic symptoms triggered by exposure to pollen. The skin prick/puncture can be used to rule out allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma triggered by cat allergen exposure. However, specific IgE assays with defined quantifiable threshold levels can also predict positive respiratory responses after allergen exposure. Skin prick testing with certain well-characterized occupational protein allergens possesses adequate sensitivity such that a negative skin test result (3-mm wheal diameter) can be used to rule out clinical allergy. A detailed dietary history, at times augmented with written diet records, is necessary to determine the likelihood that food is causing the disorder, identify the specific food, and determine the potential immunopathophysiology. In general, these tests are highly sensitive (generally 85%) but only modestly specific (approximately 40% to 80%) and therefore are well suited for use when suspicion of a particular food or foods is high. Intracutaneous (intradermal) skin tests for foods are potentially dangerous, are overly sensitive, increase the chance of a false-positive test result, and are not recommended. Based on studies in infants and children, increasingly higher concentrations of food specific IgE antibodies (reflected by increasingly larger percutaneous skin test size and/or higher concentrations of food specific serum IgE antibody) correlate with an increasing risk for a clinical reaction. A trial elimination diet may be helpful to determine if a disorder with frequent or chronic symptoms is responsive to dietary manipulation. The rational selection, application, and interpretation of tests for food specific IgE antibodies require consideration of the epidemiology and underlying immunopathophysiology of the disorder under investigation, estimation of prior probability that a disorder or reaction is attributable to particular foods, and an understanding of the test utility and limitations. Diagnostic skin and/or specific IgE tests are used to confirm clinical sensitivity to venoms in a patient with a history of a prior systemic reaction. In the case of a history of anaphylaxis to Hymenoptera venoms, intracutaneous skin tests are generally performed to 5 of the available venoms in a dose response protocol (up to 1 g/mL [wt/vol]) when preliminary prick/puncture test results are negative. Paradoxically, as many as 16% of insect-allergic patients with negative venom skin test results have positive results on currently available specific IgE in vitro tests. A small percentage of patients (1%) with negative results to both skin and in vitro tests may experience anaphylaxis after a field sting. Because of the predictive inconsistencies of both skin and serum specific IgE tests, patients with a convincing history of venom-induced systemic reactions should be evaluated by both methods. Cross-allergenicity among insect venoms is (1) extensive among vespid venoms, (2) considerable between vespids and Polistes, (3) infrequent between bees and vespids, and (4) very limited between yellow jacket and imported fire ants. If Hymenoptera venom sensitivity is suspected, initial prick/puncture tests followed by serial endpoint titration with intracutaneous tests may be required. Nevertheless, most patients with suspected venom allergy do not require live stings. Evaluation of drug-specific IgE antibodies induced by many high-molecular-weight and several low-molecular-weight agents is often highly useful for confirming the diagnosis and prediction of future IgE-mediated reactions, such as anaphylaxis and urticaria. Neither immediate skin nor tests for specific IgE antibodies are diagnostic of cytotoxic, immune complex, or cell-mediated drug-induced allergic reactions. A graded challenge (test dose) is a procedure to determine if a drug is safe to administer and is intended for patients who are unlikely to be allergic to the given drug. In the absence of validated skin test reagents, the approach to patients with a history of penicillin allergy is similar to that of other antibiotics for which no validated in vivo or in vitro diagnostic tests are available. Therapeutic options include (1) prescribing an alternative antibiotic, (2) performing a graded challenge, and (3) performing penicillin desensitization. In patients who have reacted to semisynthetic penicillins, consideration should be given to skin test the implicated antibiotic and penicillin determinants. Skin testing with nonirritating concentrations of other antibiotics is not standardized. A positive skin test result suggests the presence of drug-specific IgE antibodies, but the predictive value is unknown. Skin testing is a useful diagnostic tool in cases of perioperative anaphylaxis, and when skin testing is used to guide subsequent anesthetic agents, the risk of recurrent anaphylaxis to anesthesia is low. Skin testing for diagnosis of local anesthetic allergy is limited by false-positive reactions. The specificity and sensitivity of skin tests for systemic corticosteroid allergy are unknown, and cases of corticosteroid allergy with negative skin test results to the implicated corticosteroid have been reported. Contact dermatitis is a common skin disorder seen by allergists and dermatologists and can present with a spectrum of morphologic cutaneous reactions. Factors that affect response to the contact agent include the agent itself, the patient, the type and degree of exposure, and the environment. Tissue reactions to contactants are attributable primarily to cellular immune mechanisms except for contact urticaria. Patch test results are affected by oral corticosteroids but not by antihistamines. Reading and interpretation of patch test results should conform to principles developed by the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group and the North American Contact Dermatitis Research Group. The role of detergents in hand dermatitis is a reflection of their ability to disrupt the skin barrier. These problems include both IgE and delayed hypersensitivity (ie, tuberculin-like and contactant allergy) adaptive immune responses. Quality assurance is also discussed in the context of reproducibility and the need to minimize intertechnician and interlaboratory variability. First described in 1867 by Dr Charles Blackley, skin tests (prick/puncture and intracutaneous) have evolved as reliable, cost-effective techniques for the diagnosis of IgE-mediated diseases. Sir Thomas Lewis had first suggested the puncture technique as an alternative skin test. Prick/puncture tests have been widely adapted throughout the world, although some practitioners prefer exclusive use of intracutaneous tests. Under carefully defined circumstances, these tests are also useful in the diagnosis of drug and chemical hypersensitivity (platinum salts, acid anhydrides, polyisocyanates, sulfonechloramide, and succinylcholine analogs) reactions. A number of sharp instruments (hypodermic needle, solid bore needle, lancet with or without bifurcated tip, and multiple-head devices) may be used for prick/puncture tests. Although a number of individual prick/puncture comparative studies have championed a particular instrument, an objective comparison has not shown a clear-cut advantage for any single or multitest device. Furthermore, interdevice wheal size variability at both positive and negative sites is highly significant. Optimal results can be expected by choosing a single prick/puncture device and properly training skin technicians in its use. Devices used in this manner generally are designed with a sharp point and a shoulder (0. Devices with multiple heads have also been developed to apply several skin tests at the same time. Lancet instruments, either coated or submerged in a well containing the allergen extract (Phazet, Prilotest), are not used in the United States. This notice led many allergists to abandon the use of solid-bore needles for percutaneous testing, resulting in greater use of the newer devices, each of which is discarded after use. Numerous studies have compared the reliability and variability of various devices. This is partially due to the degree of trauma that the device may impart to the skin, thereby accounting for different sizes of positive reactions and even the possibility of producing a false-positive reaction at the site of the negative control. Thus, prick/puncture devices require specific criteria for what constitutes a positive reaction (Table 2). To achieve quality assurance among technicians, consistency in skin test performance should be demonstrated by skin testing proficiency protocols. In Europe, a coefficient variation of less than 20% after histamine control applications has been suggested, whereas a coefficient variation of less than 30% was used in a recent Childhood Asthma Management Study. Under clinical conditions, it is impossible to quantify the exact amount of Table 2. Devices 2 are those for which a more than 3-mm wheal should be used as significant. Record histamine results at 8 minutes by outlining wheals with a felt tip pen and transferring results with transparent tape to a blank sheet of paper. Record saline results at 15 minutes by outlining wheal and flares with a felt tip pen and transferring results with transparent tape to a blank sheet of paper. Calculate the mean diameter as (D d)/2; D largest diameter and d orthogonal or perpendicular diameter at the largest width of D. In the past decade, a number of prospective epidemiologic studies have relied heavily on the prick/puncture test for evaluating increase or decrease in atopy over time. Several epidemiologic studies of this type have confirmed highly repeatable results in the short term (ranging from 1 week to 11 months). Antihistamines vary considerably in their ability to suppress wheal-and-flare responses (Table 4). Furthermore, the studies that evaluated degree and duration of antihistamine suppression were not directly comparable because they used different pharmacodynamic models (eg, histamine vs allergen induced). The general principle to be gleaned from various studies is that the use of first- and second-generation antihistamines should be discontinued 2 to 3 days before skin tests with notable exceptions being cetirizine, hydroxyzine, clemastine, loratadine, and cyproheptadine (Table 4). This effect is attributed to a combination of a decrease in mast cell recruitment and an increase of mast cell apoptosis. Suppression of endogenous cortisol may affect late-phase reactions (skin and pulmonary) without a change in early-phase responses. If they are performed in the presence of mild dermatographism, the results should be interpreted with caution. Although an early study reported that positive reactions tend to be smaller in infants and younger children (2 years) than in adults, a recent investigation of prick/ puncture tests in infants revealed that they exhibit a high degree of reliability. Maximum days would apply to most patients, but there may be exceptions where this would be longer. Degree and duration of skin test suppression and side effects with antihistamines: a double blind controlled study with five antihistamines. A comparison of the in vivo effects of ketotifen, clemastine, chlorpheniramine and sodium cromoglycate on histamine and allergen induced weals in human skin. Duration of the inhibitory activity on histamine-induced skin weals of sedative and non-sedative antihistamines. Histamine skin test reactivity following single and multiple doses of azelastine nasal spray in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Duration of the suppressive effect of tricyclic antidepressants on histamineinduced wheal-and-flare reactions in human skin. The effect of tranquilizers on the immediate skin wheal reaction: a preliminary report. Suppression of the early and late cutaneous allergic responses using fexofenadine and montelukast. Although a limited number of standardized extracts are commercially available, most inhalant and food extracts are not standardized. Before the recent availability of standardized extracts, the composition of nonstandardized, commercially available extracts varied greatly between the manufacturers. Although relatively few commercialized extracts are yet designated in bioequivalent allergy units (eg, grass, cat), the trend toward universal bioequivalency is well under way, as evidenced by more recent attempts to standardize commercial food antigen extracts not only by wheal area but also by objective organ challenges. Since it is known that allergen extracts deteriorate with time, accelerated by dilution and higher temperatures, allergen skin test extracts are usually preserved with 50% glycerin.

Gross In horses hair loss in men kurta purchase 5 mg finast mastercard, gross lesions are similar to those observed in animals dying from Eastern equine encephalomyelitis and Western equine encephalomyelitis virus infections and are not specific enough to establish an etiologic diagnosis hair loss in men 15 buy finast 5mg overnight delivery. Litters from infected pigs contain fetuses that are mummified and dark in appearance hair loss treatment after pregnancy generic finast 5 mg online. Key microscopic Histologically hair loss in menopause cures 5 mg finast sale, there is diffuse nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis with prominent perivascular cuffing hair loss cure 4 batten purchase finast 5mg line. Immunization Vaccination of horses and swine in endemic areas is advised and consists of modified live or inactivated product made from either mouse brains or cell cultures infected with a strain of the virus hair loss eczema buy 5mg finast. Samples For virus isolation, cerebrospinal fluid and/or brain from affected animals is preferred. Because swine serve as amplifying hosts for the normal mosquito-wild bird cycle, swine should be vaccinated to prevent outbreaks in endemic areas. The most promising approach to reducing livestock losses and simultaneously reducing the totality of infection in nature is widespread immunization of swine. It is anticipated that those animals retained for breeding will remain immune, and, because of immunity or natural seasonal lows in transmission, they will resist infection during pregnancy and therefore bear normal litters. Although controlling the disease in swine dampens the spread of infection in nature, there is a continued threat to horses and human beings from other sources. Nonsuppurative encephalitis in piglets after experimental inoculation of Japanese encephalitis flavivirus isolated from pigs. The disease was first recognized in 1964 when it affected Bali cattle, which are the domesticated form of the wild banteng (Bos javanicus). Three decades after it was first described, the causative agent was identified as a lentivirus. Domestic animals Severe clinical disease is seen only in Bali cattle (Bos javanicus). Other types of cattle (both Bos taurus and Bos indicus) as well as swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalus) can be infected experimentally and mild disease results. In contrast, natural disease has not been reported in any species other than Bali cattle. Wild animals Bali cattle are the domestic variety of the wild banteng (Bos javanicus). Other than disease occurring in this species, there are no reports of the disease in wild animals. Proximity of infected with noninfected animals is a circumstantial requirement, so it is presumed that contact is the main means of transmission. The virus is present in saliva and milk, and can infect via a number of mucous membranes. Mortality In the current endemic situation, case-fatality rate in Bali cattle is about 20%. The cattle can be severely ill, with death of up to 20% of clinically apparent cases. Other breeds of cattle Experimentally infected Friesian cattle had fever, lymphadenopathy, and leukopenia. There are dramatic hematologic changes, including lymphopenia, eosinopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia (pancytopenia except for monocytes). Key microscopic Lymphoblastoid response is evident in many lymphoid organs, affecting the Tcell areas and sparing the B-cell zones. In addition, lymphocytic inflammation may be seen in multiple visceral organs, especially kidney and lung. Natural infection Animals that survive the disease are resistant to a recurrence of the disease. Antibodies do not develop until several weeks postinfection but are still detectable at least a year after infection. Experimentally, inoculating animals with a suspension of bovine-derived materials containing inactivated virus resulted in partial protection. Field diagnosis Bali cattle that are febrile with enlarged superficial lymph nodes should prompt a presumptive diagnosis, with samples taken for laboratory confirmation. Samples Serum, lymph nodes, spleen, and a variety of tissues fixed in formalin should be collected. Other breeds of cattle may also be persistently viremic after infection, but the period is shorter, on the order of 36 months. Because the disease in non-Bali types of cattle may be mild, infection could go undetected and spread to new areas. Species differences in the reaction of cattle to Jembrana disease virus infection. The transmission of Jembrana disease, a lentivirus disease of Bos javanicus cattle. Evidence for immunosuppression associated with Jembrana disease virus infection of cattle. Other closely related members of this genus include yellow fever virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, Kyasanur Forest disease virus and Japanese encephalitis virus. Domestic animals Many species can be affected by this virus, including sheep, cattle, horses, pigs, goats, dogs, and llamas. Wild animals Red grouse, deer, hares, rabbits, rats, shrews, voles, and wood mice are infected naturally. Because mortality in red grouse is so extensive, they are not considered very important in the maintenance of the virus in nature. The other wild mammals are not considered important in the epidemiology of the disease. Humans Humans can be infected through tick bite, entrance of the virus through skin wounds (abattoir workers especially), aerosol exposure in the laboratory, or ingestion of contaminated milk. Transmission the virus is transmitted by the three-host sheep tick, Ixodes ricinus. Peak activity of the tick occurs in the spring, and so the majority of cases are noted at this time. Although other ticks have been shown to be capable vectors of infection, specifically, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, Ixodes persulcatus, and Haemaphysalis anatolicum, they are not thought to be important in the epidemiology of the disease. Studies have shown that the virus is present in the milk of infected ewes and does, and may be spread to lambs, kids, or humans through ingestion. Morbidity Morbidity in sheep depends on immune status and severity of virus challenge. In areas where there is widespread vaccination, morbidity may be seen only in lambs at the time of waning of colostral immunity, or in replacement breeding stock that are brought in. In sheep, mortality rates depend on the breed of sheep and the prevalence of virus, but are rarely more than 15%. The fever tends to be biphasic, with the second spike of fever coinciding with the onset of neurologic signs. Evidence of brainstem or cerebellar dysfunction is seen, including ataxia, incoordination, and characteristic hopping, or "louping" gait. As the disease progresses, more cortical function is compromised, with hypersensitivity, head-pressing, convulsions, and coma. Even those animals that recover may have persistent central nervous deficits of varying severity. There is a nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis, with perivascular and meningeal infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells and histiocytes. Natural infection Natural infection may only precipitate partial immunity and recurring viremias, which will help to disseminate the virus through the feeding on these animals. There may be no clinical signs in these reservoir animals these animals that serve as reservoirs of infection do not have any signs of disease. Vaccination of pregnant ewes during the last trimester is recommended for maximal passive immunity in lambs. If lambs are vaccinated as maternal immunity wanes, protection should be complete. Treatment of animals with acaricide to diminish tick burden and therefore viral challenge is also helpful. Role of small mammals in the persistence of Louping-ill virus: field survey and tick co-feeding studies. Clinical signs vary between species, yet within species they tend to be consistent. The most common presentation in domesticated cattle involves fever, rhinitis, depression, and bilateral keratoconjunctivitis. Clinical signs in American bison and susceptible cervid species comprise depression, diarrhea, and a short clinical course terminating in death. Of these, only 4 have clearly been shown to be pathogenic under natural conditions. They exist as well-adapted, ubiquitous infections that generally cause no disease in their respective carrier species. To date this virus has been documented to cause disease in 2 cervid species, white-tailed and Sika deer. These hosts can be divided into 2 types: well-adapted asymptomatic carriers, and poorly adapted hosts in which both disease and subclinical infections occur. The well-adapted carrier hosts include species in the subfamilies Alcelaphinae, Caprinae, and Hippotraginae. The hosts shed virus into the environment and are capable of transmitting it to clinically susceptible species when contact is close, or when indirect means of transfer of virus, such as suitable fomites, occur. Poorly adapted hosts (or clinically susceptible hosts) are generally considered not to shed infectious virus, and are therefore dead-end hosts. Clinically susceptible species are usually within the families Cervidae and Giraffidae and subfamily Bovinae. It has been reliably documented in, among others, domesticated cattle (Bos taurus and B. Increased susceptibility to disease Natural hosts Domestic sheep Blue and black wildebeest Moderately susceptible Bos taurus Bos indicus Highly susceptible American & European bison Bali cattle Water buffalo Many cervid species Gaur Bongo Predominantly hemorrhagic enteritis Lesion profile None Predominantly vasculitis/ lymphadenopathy b. Most wildebeest calves are infected perinatally by horizontal and occasional intrauterine transmission, and shed virus until 3-4 months of age. Shedding of virus from adult wildebeest is rare, but can be induced by stress or steroid administration. Adolescents between 6-9 months of age are the highest risk group for transmission. Mechanical vectors and contaminated water or feed materials may play a role in transmission. Maximal transmission distances depend on several factors, including viral load and climatic conditions, which influence virus survival time. Reported incubation periods of more than several months may represent recrudescence of previously established infections. These reports tend to enter the literature due to the unusually high rates of loss. In bison, morbidity approaches 50% when there is close contact between sheep and bison and/or exposure to large flocks. Recovery is now well documented, but such cattle may develop recrudescent disease or remain unthrifty. Once clinical signs appear, mortality rates in American and European bison, susceptible cervid species, water buffalo and banteng approach 100%. Cattle develop bilateral mucoid nasal discharge that becomes mucopurulent, profuse, and, in some, hemorrhagic. There is severe bilateral keratitis, manifested as opacity of the cornea with epiphora and hypopyon. American bison, Bali cattle, and many of the susceptible cervid species the clinical course is shorter (1-3 days) than in cattle. Handling of apparently mildly depressed bison in chutes may precipitate death or inhalation pneumonia. The primary manifestation is severe depression, separation from the herd, dehydration, and weight loss. Nasal discharge, crusting of the muzzle and corneal opacity is less pronounced in bison and deer than in cattle. In bison, epiphora is more difficult to detect from a distance due to the thick hair coat. Disease has been seen in unweaned calves, although bison and deer older than 6 months are most likely to develop disease. Some sporadic outbreaks of panvasculitis syndrome(s) in sheep (so called polyartertis nodosa) may be the spontaneous correlate of this experimental phenomenon. Lesions in gut can be hard to identify, particularly in moderately autolytic carcasses. Severity varies from multifocal mucosal ecchymoses to severe hemorrhagic cystitis with intraluminal blood. Other lesions are erosions and ulcers of oral mucosa (especially tongue, and hard and soft palate), fauces, esophagus, forestomachs, and abomasum. Identical lesions occur in the larynx, but rarely extend any distance down the trachea. Bison and cervid species generally have diffuse to segmental typhlocolitis, which is the presumed basis for diarrhea/melena. This is best detected by attempting to wash off luminal contents; if material remains adherent in minimally autolytic carcasses, it is strongly suggestive of typhlocolitis.