|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Ziad Obermeyer MD

https://publichealth.berkeley.edu/people/ziad-obermeyer/

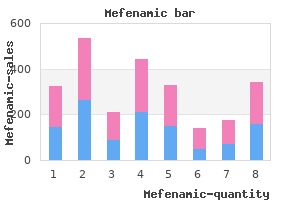

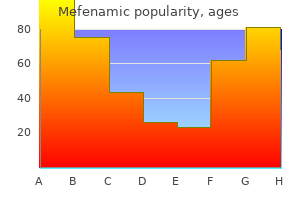

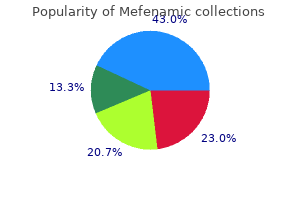

Importantly muscle relaxant drugs over the counter mefenamic 500mg online, they satisfy the weak transfer principle and thus guarantee that in the face of a regressive transfer anywhere along the distribution spasms parvon plus buy cheap mefenamic 250 mg on-line, inequality measured by any of these indices will never decline but muscle relaxant topical cream cheap 500 mg mefenamic visa, notably spasms back pain and sitting trusted mefenamic 500 mg, it can stay the same muscle relaxant neck pain order 500 mg mefenamic mastercard. Examples include the quantile ratios (such as the income of percentile 90 to the income of the 10th percentile also known as the p90/p10 ratio) and the variance of logarithms spasms right side discount 500 mg mefenamic mastercard. For example, a transfer from the 5th percentile to the 10th would reduce the p90/p10 ratio despite the fact that the transfer is clearly regressive because it redistributes income from the very poor to the less poor. Regressive transfers at the upper end of the distribution can lower the variance of logarithms and lead to extreme conflicts with the Lorenz criterion. Virtually every inequality measure is a ratio of two "income standards" that summarize the size of the income distributions from two perspectives: one that emphasizes higher incomes and a second that emphasizes lower incomes. This index satisfies the first three principles but can violate the weak transfer principle when the regressive transfer Chapter 3 Measuring inequality in income and wealth 137 raises the median income. Like the other partial indices, it is weaker in terms of the properties it satisfies but has the advantage of simplicity and is often used in political economy. One can conclude from this that any reasonable (that is, Lorenz consistent) measure would agree that inequality has unambiguously increased or declined, according to what the Lorenz curves indicates. However, it is also possible that the Lorenz curves cross, in which case reasonable inequality measures can disagree. One approach is to narrow the set of reasonable inequality measures using an additional criterion. For instance, transfer-sensitive measures are Lorenz consistent measures that emphasize distributional changes at the lower end over those at the upper end. The Atkinson class and the two Theil measures (including the mean log deviation) are transfer-sensitive measures. By contrast, the coefficient of variation (standard deviation divided by the mean) is neutral with respect to where transfers occur, while many other generalized entropy measures emphasize distributional changes at the upper end and thus are not in the set of transfer-sensitive measures. As a subset of Lorenz-consistent measures, they agree when Lorenz curves do not cross as well as in many cases when they do cross. For example, suppose that Lorenz curves cross once and that the first Lorenz curve is higher at lower incomes than the second. There is a simple test: the first has less inequality than the second, according to all transfer-sensitive measures exactly when the coefficient of variation for the first is no higher than that for the second. If not, the conclusion is ambiguous for that set of measures, with inequality ranked one way for some measures and reversed for others. Frequency 9 4 3 3 Thus, the most frequently reported inequality measures include two that are Lorenz consistent (the Gini and Theil measures), one that is weakly Lorenz consistent (the top 10 percent) and one that is neither (the 90/10 quantile ratio). In addition to inequality measures, international datasets report other statistics. The resulting Lorenz curve is an approximation of the actual Lorenz curve where inequality within each group has been suppressed. For example, one Atkinson measure compares the higher arithmetic mean to the lower geometric means; the 1 percent income share effectively compares the higher 1 percent mean to the lower arithmetic mean. See also Zheng (2018), who presents additional criteria for making comparisons when Lorenz curves cross. For example, they publish prefiscal and postfiscal Gini coefficients and other indicators of inequality and poverty. Standard fiscal incidence analysis just looks at what is paid and what is received without assessing the behavioural responses that taxes and public spending may trigger for individuals or households. That is, starting from a prefiscal income concept, each new income concept is constructed by subtracting taxes and adding the relevant components of public spending to the previous income concept. While this approach is broadly the same across all five databases mentioned, the definition of the specific income concepts, the income concepts included in the analysis and the methods to allocate taxes and public spending differ. This spotlight focuses on comparing the definition of income concepts-that is, on the types of incomes, taxes and public spending included in the construction of the prefiscal and postfiscal income concepts. There are important differences, and some can have significant implications for the scale of redistribution observed. The following table compares the definitions of income used by the six databases mentioned above. This is important because the prefiscal income is what each database uses to rank individuals prior to adding transfers and subtracting taxes and will thus affect the ensuing redistribution results (see point on the treatment of pensions below). There is also a fundamental difference in the treatment of contributory pensions (see the next paragraph). Finally, the World Inequality Database also includes undistributed profits in its definition of prefiscal income. This assumption can make a significant difference in countries with a high proportion of retirees whose main or sole income stems from old-age pensions. For example, in the European Union the redistributive effect with contributory pensions as pure transfers is 19. The difference is probably an overestimation because in many cases one cannot distinguish between contributory and social pensions. Equivalized income equals household income divided by the square root of household members (excluding domestic help). Chapter 3 Measuring inequality in income and wealth 143 Chapter 4 Gender inequalities beyond averages: Between social norms and power imbalances 4. Gender inequalities beyond averages: Between social norms and power imbalances Gender disparities remain among the most persistent forms of inequality across all countries. All too often, women and girls are discriminated against in health, in education, at home and in the labour market-with negative repercussions for their freedoms. Progress in reducing gender inequality over the 20th century was remarkable in basic achievements in health and education and participation in markets and politics (figure 4. Based on current trends, it would take 202 years to close the gender gap in economic opportunity. The silence breakers were also given voice by the #MeToo movement, which uncovered abuse and vulnerability for women, well beyond what is covered in official statistics. In Latin America, the world is not on track to achieve gender equality by 2030 Enhanced capabilities Agency and change Social norms Tradeoffs/ power imbalances Subsistence and participation Basic capabilities Source: Human Development Report Office. Chapter 4 Gender inequalities beyond averages-between social norms and power imbalances 147 Gender inequality is correlated with a loss in human development due to inequality too, the #NiUnaMenos movement has shed light on femicides and violence against women from Argentina to Mexico. In several countries the gender equality agenda is being portrayed as part of "gender ideology. This implies that progress is easier for more basic capabilities and harder for more enhanced capabilities (chapter 1). The first trend indicates the urgency in addressing gender inequality to promote basic human rights and development. Social and cultural norms often foster behaviours that perpetuate inequalities, while power concentrations create imbalances and lead to capture by powerful groups such as dominant, patriarchal elites. Both affect all forms of gender inequality, from violence against women to the glass ceiling in business and politics. In addition, gender-specific tradeoffs burden the complex choices women encounter in work, family and social life-resulting in cumulative structural barriers to equality. The tradeoffs are influenced strongly by social norms and by a structure of mutually reinforcing gender gaps. These norms and gaps are not directly observable, so they are often overlooked and not systematically studied. Gender inequality in the 21st century Gender inequality is intrinsically linked to human development, and it exhibits the same dynamics of convergence in basic capabilities and divergence in enhanced capabilities. Overall, it is still the case-as Martha Nussbaum has pointed out-that "women in much of the world lack support for fundamental functions of a human life. In Sub-Saharan Africa 1 in every 180 women giving birth dies (more than 20 times the rate in developed countries), and adult women are less educated, have less access to labour markets than men in most regions and lack access to political power (table 4. Gender inequality as a human development shortfall Gender inequality is correlated with a loss in human development due to inequality (figure 4. No country has reached low inequality in human development without restricting the loss coming from gender inequality. The conclusion: "These impressions are cause for hope, not pessimism, for the future. The space for gains based on current strategies may be eroding, and unless the active barriers posed by biased beliefs and practices that sustain persistent gender inequalities are addressed, progress towards equality will be far harder in the foreseeable future. As chapter 1 discussed, progress in human development is linked to expanding substantive freedoms, capabilities and functionings from basic to more enhanced. Progress towards equality tends to be faster for basic capabilities and harder for enhanced capabilities. Legal barriers to gender equality have been removed in most countries: Women can vote and be elected, they have access to education, and they can participate in the economy without formal restrictions. But progress has been uneven as women pull away from basic areas into enhanced ones, where gaps tend to be wider. The higher the loss due to gender inequality, the greater the inequality in human development. The past two decades have seen remarkable progress in education, almost reaching parity in average primary enrolment, and in health, reducing the global maternal mortality ratio by 45 percent since 2000. Women make greater and faster progress where their individual empowerment or social power is lower (basic capabilities). But they face a glass ceiling where they have greater responsibility, political leadership and social payoffs in markets, social life and politics (enhanced capabilities) these patterns can be interpreted as reflecting the distribution of individual empowerment and social power: Women make greater and faster progress where their individual empowerment or social power is lower (basic capabilities). But they face a glass ceiling where they have greater responsibility, political leadership and social payoffs in markets, social life and politics (enhanced capabilities) (figure 4. This view of gradients in empowerment is closely linked to the seminal literature on basic and strategic needs coming from gender planning (box 4. So there is parity in entry-level political participation, where power is very diffused. But when more concentrated political power is at stake, women appear severely under-represented. The higher the power and responsibility, the wider the gender gap-and for heads of state and government it is almost 90 percent. Only 24 percent of national parliamentarians were women in 2019,13 and their portfolios were unevenly distributed. Women most commonly held portfolios in environment, natural resources and energy, followed by social sectors, such as social affairs, education and family. Certain disciplines are typically associated with feminine or masculine characteristics, as also happens in education and the labour market. When empowerment is basic and precarious, women are over-represented, as for contributing family workers (typically not receiving monetary payment). Then, as economic power increases from employee to employer, and from employer to top entertainer and billionaire, the gender gap widens. Empowerment gradients appear even for a uniform set of companies, as with the gender leadership gap in S&P 500 companies. In developing countries most women who receive pay for work are in the informal sector. Countries with high female informal work rates include Uganda, Paraguay, Mexico and Colombia (figure 4. As articulated in gender social policy analyses,2 practical gender needs refer to the needs of women and men to make everyday life easier, such as access to water, better transportation, child care facilities and so on. Strategic gender needs refer to needs for society to shift in gender roles Notes 1. Sometimes practical and strategic needs coincide-for example, the practical need for child care coincides with the strategic need to get a job outside the home. Today, women are the most qualified in history, and newer generations of women have reached parity in enrolment in primary education. Some represent a natural part of the process of development-the constant need to push new boundaries to achieve more. Others represent the response of deeply rooted social norms to preserve the underlying structure of power. Gender inequality has long been associated with persistent discriminatory social norms prescribing social roles and power relations between men and women in society. Women often face strong conventional societal expectations to be caregivers and homemakers; men similarly are expected to be breadwinners. So, despite convergence on some outcome indicators-such as access to education at all levels and access to health care-women and girls Gender inequality has long been associated with persistent discriminatory social norms prescribing social roles and power relations between men and women in society in many countries still cannot reach their full potential. Norms influence expectations for masculine and feminine behaviour considered socially acceptable or looked down on. Intersectionality is the complex, cumulative way the effects of different forms of discrimination combine, overlap or intersect-and are amplified when put together. It recognizes that policies can exclude people who face overlapping discrimination unique to them. Overlapping identities must be considered in research and policy analysis because different social freedom, and beliefs about social censure and reproach create barriers for individuals who transgress. For gender roles these beliefs can be particularly important in determining the freedoms and power relations with other identities-compounded when overlapping and intersecting with those of age, race and class hierarchies (box 4. These are difficult questions, norms and stereotypes of exclusion can be associated with different identities. For instance, regarding median years of education completed in Angola and United Republic of Tanzania, an important gap distinguishes women in the highest wealth quintile from those in the second or lowest quintile (see figure). If the differences are not explicitly considered, public programmes may leave women in the lowest quintiles behind. People who identify with multiple minority groups, such as racial minority women, can easily be excluded and overlooked by policies. But the invisibility produced by interacting identities can also protect vulnerable individuals by making them less prototypical targets of common forms of bias and exclusion.

A 2005 study demonstrated that over 90% of dairy cows in the northeastern United States are infected with C burnetii spasms pelvic floor buy mefenamic 500mg cheap,102 but pasteurization prevents human infection via consumption of contaminated milk muscle relaxant tinnitus cheap mefenamic 500mg overnight delivery. Although exposure via contaminated milk can be prevented by simply pasteurizing milk muscle relaxant histamine release mefenamic 250mg online, infection by the aerosol route (ie spasms while high cheap mefenamic 250mg with visa, inhalation of dried infectious particles shed by infected animals) cannot be prevented muscle relaxant 4212 trusted mefenamic 250mg. Without obvious symptoms spasms of pain from stones in the kidney purchase mefenamic 250mg online, it is difficult to identify infected animals and therefore next to impossible to eradicate C burnetii from domestic animals. History of exposure to animals or time spent on farms bolsters what is usually a presumptive diagnosis. Humoral responses are more consistently activated during Q fever infection than cellular responses and, as such, serological testing is considered the more reliable immunoassay for Q fever. Complement fixation is one of the most specific assays for diagnosing Q fever, but it lacks sensitivity and cannot detect specific antibody early in the course of an infection. Acute and chronic Q fever produce characteristic, yet distinct, antibody profiles. Individuals with chronic infection have an antibody profile exactly opposite the profile of individuals with acute infection. Although it is possible to diagnose Q fever based on bacterial culture, this method is not widely used. C burnetii is highly infectious and must be grown under biosafety level 3 conditions, a requirement that is not feasible at most medical treatment facilities. Culturing C burnetii from patient samples can be done by using the sample to infect research animals such as mice, or by infecting a monolayer of cells and subsequently staining and visualizing the cocci. These methods are very time consuming and are not conducive for large numbers of samples. Detection by quantitative polymerase chain reaction is also a viable method and can be used to detect the bacteria in the infected individual much earlier than methods that rely on the production of antibody. The nucleic acid amplification test by Idaho Technologies produces results within 4 hours. In cases with endocarditis, an 18-month regimen of 100 mg of doxycycline twice per day and 200 mg of chloroquine three times per day is effective. Doxycycline is not bactericidal, but is an effective treatment for intracellular bacteria such as C burnetii and Chlamydia. The effectiveness of doxycycline is improved when used in combination with hydroxychloroquine and it is hypothesized that the hydroxychloroquine increases the pH of the phagolysosome, which would decrease the metabolic activity of C burnetii. The failure of most of these vaccines has been the inability to uncouple the protection and the accompanying adverse reactions. Within a few years of identifying C burnetii, researchers had successfully developed an effective vaccine. Knowledge of the phase variation that occurs in C burnetii came after this early vaccine was developed. There is no question that these vaccines are highly protective against Q fever, but the side effects that occur in a specific population of people has prevented their wide-spread use. Individuals that have been exposed to C burnetii prior to vaccination, such as those who have had Q fever or have spent significant time in close proximity to livestock, are very likely to have adverse reactions at the site of injection. Scientists at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases vaccinated with the residue from chloroform and methanol extracted from phase I organisms that had been formalin inactivated. They have demonstrated that the vaccine is protective in animals, nontoxic, and immunogenic in humans. Studies using a low-dose prime-boost scheme have shown success in animals and induce protection without reaction. Q fever significantly impacted wartime efforts as recently as the past few years, and as evidenced by the recent outbreak in the Netherlands, can produce prolific disease even in areas with sufficient preparation. The ubiquitous nature of C burnetii in the environment indicates that Q fever will be a concern for years to come; not only does it have the potential to produce disease in humans, it can also result in devastating losses to domestic animals. Extremely resistant to environmental stresses, C burnetii can persist for long periods of time in the environment. Q fever is easily treated by antibiotics of the tetracycline class, though diagnosis can be difficult based on the nonspecific symptoms observed in Q fever patients. Physicians must rely on a combination of clinical presentation and serological testing to diagnose Q fever. Although the vaccine used in Australia is not available for use in the United States, efforts continue to find a safe and efficacious alternative. The cultivation of Rickettsia diaporica in tissue culture and in tissues of developing chick embryos. Q fever in military and paramilitary personnel in conflict zones: case report and review. Potential for Q Fever Infection Among Travelers Returning from Iraq and the Netherlands. Biochemical stratagem for obligate parasitism of eukaryotic cells by Coxiella burnetii. Characterization of a Coxiella burnetii ftsZ mutant generated by Himar1 transposon mutagenesis. Alpha(v)beta(3) intergrin and bacterial lipopolysaccaride are involved in Coxiella burnetii-stimulated production of tumor necrosis factor by human monocytes. Coxiella burnetii induces reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in human monocytes. Differential interaction with endocytic and exocytic pathways distinguish parasitophorous vacuoles of Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia trachomatis. Coxiella burnetii inhabits a cholesterol-rich vacuole and influences cellular cholesterol metabolism. Maturation of the Coxiella burnetii parasitophorous vacuole requires bacterial protein synthesis but not replication. Sustained activation of Akt and Erk1/2 is required for Coxiella burnetii antiapoptotic activity. Stimulation of toll-like receptor 2 by Coxiella burnetii is required for macrophage production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and resistance to infection. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase activity of Coxiella burnetii that inhibits human neutrophils. Comparative genomics reveal extensive transposon-mediated genomic plasticity and diversity among potential effector proteins within the genus Coxiella. Turning a tiger into a house cat: using Legionella pneumophila to study Coxiella burnetii. Functional similarities between the icm/dot pathogenesis systems of Coxiella burnetii and Legionella pneumophila. Isolation from animal tissue and genetic transformation of Coxiella burnetii are facilitated by an improved axenic growth medium. The Coxiella burnetii Dot/Icm system creates a comfortable home through lysosomal renovation. Coxiella burnetii isolates cause genogroup-specific virulence in mouse and guinea pig models of acute Q fever. Air-borne transmission of Q fever: the role of parturition in the generation of infective aerosols. Q fever in California; recovery of Coxiella burnetii from naturally-infected air-borne dust. Q fever studies in Southern California; recovery of Rickettsia burnetii from raw milk. Seroepidemiology of Q fever in Nova Scotia: evidence for age dependent cohorts and geographical distribution. Upregulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 beta in Q fever endocarditis. Production of interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor beta by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in Q fever endocarditis. Evaluation of specificity of indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of human Q fever. Evaluation of the complement fixation and indirect immunofluorescence tests in the early diagnosis of primary Q fever. Humoral immune response to Q fever: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay antibody response to Coxiella burnetii in experimentally infected guinea pigs. Development of a chloroform:methanol residue subunit of phase I Coxiella burnetti for the immunization of animals. Treatment of Q fever endocarditis: comparison of 2 regimens containing doxycycline and ofloxacin or hydroxychloroquine. Serologic and skin-test response after Q fever vaccination by the intracutaneous route. Low-dose priming before vaccination with the phase I chloroformmethanol residue vaccine against Q fever enhances humoral and cellular immune responses to Coxiella burnetii. Acinetobacter species are environmentally hardy and difficult to eradicate from inanimate healthcare surfaces, but their relatively low virulence makes them poor candidates for weaponizing. In fact, even in the most severely war-wounded patients, Acinetobacter species infections are rarely fatal. Treatment of traumatic wound infections has evolved over time, as a belief in "laudable pus" yielded to surgical debridement, and the emergence of penicillin in 1942 ushered in a period when recovery from serious infections became possible, if not expected. However, the 21st century has witnessed the expansion of bacteria that are resistant to multiple antibiotics, and a dearth in new drug development has resulted in infections from bacteria that are resistant to virtually all available antibiotics. Bacteria of the genus Acinetobacter are glucose nonfermentative, nonfastidious, catalase-positive, oxidase-negative, strictly aerobic, gram-negative, coccobacilli (or pleomorphic) and commonly occur in 322 diploid formation or in chains of variable length. However, different genospecies cannot be easily identified using traditional methods. Members of the genus have been classified in various ways; therefore it is difficult to understand the true status of the epidemiology and clinical importance of these organisms. Since 1986, the taxonomy of the genus Acinetobacter has undergone extensive revision. Identifying the members of the genus Acinetobacter to the species level by traditional methods is problematic. Molecular methods are needed to identify members of the complex to the species level because each member has a distinct antimicrobial susceptibility profile and shows different clinical characteristics. These have gained notoriety for a predilection to cause nosocomial infections and to develop resistance to multiple antibiotics. Furthermore, the organism was not prevalent in other studies of combat wounds during either war. Specifically, 36% of wound isolates and 41% of bloodstream isolates were of Acinetobacter species. Originally published in Infecton Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2008;29:661-63. Fortunately, renal function returned to normal once colistimethate sodium was stopped. However, its emergence as a pathogen associated with war trauma was unexpected, as was the breadth of its clinical presentation (including bacteremia, skin and soft-tissue infection, meningitis, and osteomyelitis). Traumatically wounded patients are cloistered in an intensivecare environment, supported by invasive medical devices (ventilators, chest tubes, urinary catheters and intravenous lines), and administered antibiotics that invariably select for resistant pathogens. Descriptive and risk-factor analysis, identification of sources of infection, and recommendations for control, prevention, and future surveillance were all expected. Twenty principal personnel, including four 324 civilians, provided data or conducted local studies to support the investigation; these included clinicians, epidemiologists, infection control practitioners, microbiologists, an environmental scientist, and a statistical programmer. The results are in the Molecular Analysis section, but key to the issue of strain importation was the demonstration that 43 patients treated at 4 different military hospitals were infected with related strains from a single cluster group which, in turn, was genetically related to an isolate derived from environmental sampling of an operating room in the Baghdad field hospital. This can also occur when reliance on routine cultures fails to distinguish A baumannii, the species most often causing opportunistic infection, from clinically less-significant species. Thus, a separate focus on clinical specimens, and the subjecting of both clinical and environmental isolates to species identification and molecular typing, provided critical data for the investigation. Also sampled were personnel working directly with patients while receiving, flying with, or transferring them. Three samples were taken from personnel working with patients from both the gloves and hands of caregivers. On hospital day 11, there was a sudden clinical deterioration, requiring the patient to be transferred to intensive care and mechanically ventilated. However, an isolate completely matching that of the deceased was obtained from a patient staying in a different room on the same ward. This favored transmission by healthcare personnel over fomites in the room as an explanatory mechanism in this case. Pre-hospital, primary wound infections in theater are not likely to have a significant role in transmission. The formal investigation described in the previous section was launched the following year. Initially, there was concern that the infections caused by Acinetobacter may have been due to an intentional release of the organism. The antibiotic susceptibility profiles among these three isolates were 327 Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare also similar. These results suggested that there was a common origin for the Acinetobacter isolates causing wound infections in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Research, epidemiological investigation, and molecular typing indicated that the Acinetobacter infections were nosocomial such that casualties were becoming infected in theater, then the organism was becoming disseminated through the medical evacuation chain. This was possibly due to effective countermeasures, such as sanitation and specific early therapy that resulted in reduction of less fit Acinetobacter strains both in patients and in the environment.

The mode is the only measure of central tendency that is appropriate when a nominal scale is used muscle relaxant for headache order mefenamic 500 mg mastercard. The mode simply indicates the most frequently occurring value in the distribution muscle relaxant 563 pliva mefenamic 250 mg discount. A measure of variability is a number that characterizes the amount of spread in a distribution of scores muscle relaxant drug list purchase 250 mg mefenamic. One measure of variability is the standard deviation spasms from kidney stones generic mefenamic 250 mg mastercard, which is represented by the symbol s spasms neck buy discount mefenamic 500mg on line. The standard deviation is derived by first calculating the variance muscle relaxant yellow house discount mefenamic 500 mg without a prescription, symbolized as s2 (the standard deviation is the square root of the variance). When the standard deviation 233 is small, the mean provides a good description of the data because the scores do not vary much around the mean. In contrast, when scores are widely dispersed around the mean, the standard deviation is large, and the mean does not describe the data well. Together, the mean and the standard deviation provide a great deal of information about the distribution. Note that, as with the mean, the calculation of the standard deviation uses the actual values of the scores; thus, the standard deviation is appropriate only for interval and ratio scale variables. Another measure of variability is the range, which is simply the difference between the highest score and the lowest score. Using this approach, the range for the intramural group is 1-5; for the aerobics group the range is 3-7. This is more informative because a range of a particular size can be obtained from a variety of beginning and end points. The range is the least useful of the measures of central tendency because it looks at extreme values without considering the variability in the set of scores. Recall that line graphs and bar graphs were used in Chapter 12 to illustrate the concept of interactions in 2 X 2 factorial designs. Both line and bar graphs are frequently used to express relationships between levels of an independent variable. In both graphs we see that the mean number of referrals for discipline problems is lower in the intramural sports group than in the aerobics group. It is interesting to note a common trick that is sometimes used by scientists and all too commonly by advertisers. The trick is to exaggerate the distance between points on the measurement scale to make the results appear more dramatic than they really are. Suppose, for example, that a survey reports that 52% of the respondents support national education standards advocated by Goals 2000, and 48% prefer that individual states continue to determine curriculum standards. The moral of the story is that it is always wise to look carefully at the numbers on the scales depicted in graphs. Graphing the means provides an idea of the relationship between the experimental groups on the dependent variable. The computation of descriptive statistics such as the mean and the standard deviation also helps the researcher understand the results by describing characteristics of the sample. Their results are based on sample data that are presumed to be representative of the population from which the sample was drawn (see sampling in Chapter 8). If you want to make statements about the populations from which samples were drawn, it is necessary to use inferential statistics. Are we confident that the means of the aerobics and intramural sports groups are sufficiently different to infer that the difference would be obtained in an entire population Is that difference large enough to conclude that sports participation has a positive effect on discipline Equivalency of groups is achieved by experimentally controlling all other variables or by randomization. The assumption is that if the groups are equivalent, any differences in the dependent variable must be due to the effect of the independent variable. However, it is also true that the difference between any two groups will almost never be zero. In other words, there will be some difference in the sample means, even when all of the principles of experimental design are utilized. Random or chance error will be responsible for some difference in the means even if the independent variable had no effect on the dependent variable. The point is that the difference in the sample means reflects true difference in the population means. Inferential statistics allow researchers to make inferences about the true dif" ference in the population on the basis of the sample data. Specifically, inferential statistics give the probability that the difference between means reflects random error rather than a real difference. One way of thinking about inferential statistics is to use the concept of reliability that was introduced in Chapter 4. Recall that reliability refers to the stability or consistency of scores; a reliable measure will yield the same score over and over again. Inferential statistics allow researchers to assess whether the results of a study are reliable. You could, of course, repeat your study many times, each time with a new sample of research participants. Instead, inferential statistics are used to tell you the probability that your results would be obtained if you repeated the study on many occasions. Inferential Statistics Hypothesis Testing Statistical inference usually begins with a formal statement of the null hypothesis and a research (or alternate) hypothesis. The null hypothesis, traditionally symbolized as H o, states that the population means are equal. Any difference between the means is due only to random error, not to some systematic effect of the independent variable. The research hypothesis, traditionally symbolized as Hi> states that the population means are not equal. This means that the independent variable has an effect on the dependent variable; only by having an effect will the group means turn out to be different because the groups were equivalent at the beginning. In our example on sports participation, the null and research hypotheses are: H o (null hypothesis): the population mean of the intramural sports group is equal to the population mean of the aerobics group. Notice that the research hypothesis does not state a direction for the effect; it does not state that the aerobics group will have more or fewer referrals. The nondirectional, generic form of the research hypothesis simply states that there is a difference between the means. The logic of the null hypothesis is this: If we can determine that the null hypothesis is incorrect, we reject the null hypothesis, and then we accept the research hypothesis as correct. Rejecting the null hypothesis means that the independent variable had an effect on the dependent variable. Formal hypothesis testing begins with an assumption that the null hypothesis is true. Then inferential statistics are used to establish if this hypothesis accurately represents the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. The null hypothesis is used because it is a very precise statement-the population means are exactly equal. This permits us to know the exact probability of the outcome of the results occurring if the null hypothesis is correct. The null hypothesis is rejected when there is a very low probability that the obtained results could be due to random error. Significance indicates that there is a low probability that the difference between the obtained sample means was due to random error. Probability Probability is the likelihood of the occurrence of some event or outcome. For example, if you say that there is a high probability that you will get an A in this course, you mean that there is a high likelihood that this will occur. Your probability statement is based on specific information, such as your grades on examinations. The weather forecaster says there is a 10% chance of rain today; this means that the likelihood of rain is very low. A gambler gauges the probability that a particular horse will win a race on the basis of the past performance of that horse. We want to specify the probability that an event (in this case, a difference between means in the sample) will occur if there is no difference in the actual population. The question is, what is the probability of obtaining this result if only random error is operating If this probability is very low, we reject the possibility that only random or chance error is responsible for the obtained difference in means. Do these means differ because of random error, or does participation in sports have a significant effect on girls, improving their school behavior If there is a low probability of these means occurring, then we have a statistically significant effect. We then reject the null hypothesis because the groups are not identical after all. On a practical level, this would suggest that we might want to encourage participation in extracurricular activities to influence academic performance and diminish school dropouts. If there is a high probability that the means occurred due to chance alone, the null hypothesis is supported. Probability: the Case of the Gifted Baby the use of probability in statistical inference can be understood intuitively from a simple example. Suppose that a friend claims that she has taught her gifted l-yearold daughter to read by using flash cards. A different word is presented on each card, and the baby is told to point to the corresponding object presented on a response card. The null hypothesis in your study is that only random error is operating; the baby cannot read. The research hypothesis is that the number of correct answers shows more than just random or chance guessing; the baby can read (or possibly, the baby has learned to associate the correct objects with the different colors used as backgrounds on the flash cards). You can easily determine the number of correct answers to expect if the null hypothesis is correct. Ifin the actual experiment more than 1 correct is obtained, can you conclude that the data reflect something more than just random guessing Then you probably conclude that only guessing is involved, because you recognize that there is a high probability that there would be two correct answers. Even though only one correct response is expected under the null hypothesis, small deviations away from the expected one correct answer are highly likely. Your conclusion is based on your intuitive judgment that an outcome of 70% correct is very unlikely. At this point, you would decide to reject the null hypothesis and state that the result is significant. A significant result is one that is very unlikely if the null hypothesis is correct. Because of the small likelihood that random error is responsible for the obtained results, the null hypothesis is rejected. Sampling Distributions You may have been able to judge intuitively that obtaining seven correct on the 10 trials is very unlikely. Also, as intuition indicates, an outcome of two correct is highly probable, but an outcome of seven correct has a very low probability of occurrence and can be considered highly unlikely. The sampling distribution is based on the assumption that the null hypothesis is true; in the gifted baby example, the null hypothesis is that the baby is only guessing and should therefore get 10% correct. If you were to conduct the study over and over again, the most frequent finding would be 10%. However, because of the random error possible in each sample, there is a certain possibility associated with other outcomes. Outcomes that are close to the expected null hypothesis value of 10% are very likely. However, outcomes further from the expected result are less and less likely if the null hypothesis is correct. When the baby gets seven correct responses, the probability of this occurring is so small if the null hypothesis is true that you are forced to reject the null hypothesis. Obtaining seven correct does not really belong in the sampling distribution specified by the null hypothesis that the baby cannot read -you must be sampling from a different distribution (one in which the baby may actually read! All statistical tests rely on sampling distributions to determine the probabil- 239 Table 14. The decision to reject the null hypothesis is based on probabilities rather than on certainties. The decision is made without direct knowledge of the true state of affairs in the population because you only tested a sample of individuals from the population, not every member of the population. Thus, the decision might not be correct; errors may result from the use of inferential statistics. In fact, 5% of the time the results were due to chance only, not a "real" effect as your decision rule would suggest. The left side of the matrix displays your decision about the null hypothesis based on the sample of participants you assessed. Recall that statistical decisions are always about the null hypothesis, so there is no need to be concerned about the research hypothesis at this point. You have only two choices: (1) reject the null hypothesis, or (2) accept the null hypothesis.

Among many other benefits muscle relaxant you mean whiskey buy generic mefenamic 500mg on-line, livestock can also help cushion households from negative impacts of shocks spasms face order mefenamic 500mg on line, such as droughts spasms in 6 month old baby cheap mefenamic 250 mg line. The loss ratio varies but has been estimated to be as high as 90 percent muscle relaxant withdrawal symptoms order 500 mg mefenamic overnight delivery,108 making animals a highly inefficient source of calories for people spasms translation 500 mg mefenamic. For each calorie back spasms 9 months pregnant cheap 500mg mefenamic overnight delivery, the production of animal foods requires much more land and resources than the production of an equivalent amount of plantbased foods. For many major agricultural products, greenhouse gas emissions vary widely across farms. The problem is concentrated at the top: the majority of emissions from beef herders come from the highest impact 25 percent of producers. One-size-fits-all approaches are unlikely to work, but significant opportunities exist to reduce variability among farms and mitigate the environmental impacts of beef, livestock and agricultural production generally. Reducing losses across the supply chain is another option, as is reducing demand for meat where possible and appropriate. For instance, on a per unit of protein basis, greenhouse gas emissions from the bottom 10 percent of beef producers still exceed those from peas by a factor of 36. On a per capita basis, high- and middle-income countries might benefit more, owing to reduced red meat consumption and lower energy intakes. Han and others forthcoming; Vernooij and others forthcoming; Zeraatkar, Han and others forthcoming; Zeraatkar, Johnston and others forthcoming. There are clear inequalities in spending on meat across income quintiles, but as incomes increase, inequalities in meat consumption decline. An estimated 31 start-ups are working to become the first company to market synthetic animal protein. And if these foods offer additional benefits in reducing noncommunicable diseases, they could exacerbate health inequalities. Global water withdrawal has nearly septupled over the last century, outpacing population growth by a factor of 1. Much analytical, management and policy work remains at the national level and at smaller spatial scales, such as the basin. By some estimates, as many as 4 billion people, about two-thirds of the global population, live under conditions of severe water scarcity for at least one month of the year. The 2006 Human Development Report argues forcefully that limits on physical supply are not the central problem but rather that "the roots of the crisis in water can be traced to poverty, inequality and unequal power relationships, as well as flawed water management policies that exacerbate scarcity. Every country has a national water footprint, the amount of water produced or consumed per capita. The footprint includes virtual water, which is the water used in the production of such goods as food or industrial products. Across countries, agriculture constitutes the single greatest component (92 percent) of the water consumption footprint, with cereals the largest subcomponent (27 percent), followed by meat (22 percent) and milk products (7 percent). Indeed, some of them have national water footprints of consumption on par, or exceeding, those in developed countries. Consider access to safe drinking water and sanitation, where significant inequalities persist between and within countries. Globally, over the past two decades the gaps have narrowed, falling from 47 percentage points to 32 for safely managed water services and from 14 percentage points to 5 for safely managed sanitation services. In some, basic water and sanitation coverage for the wealthiest quintile is at least twice that for the poorest quintile (figure 5. For water, wealth inequalities generally exceed urban-rural ones within the same country. While water and sanitation coverage has generally improved over the past two decades across most, but not all, countries, inequalities by wealth have shown no such general trend. Increasingly severe water-related crises around the world are driving what some have argued is a fundamental transition in freshwater resources and their management. Approaches that focus singularly on meeting water demand are giving way to more multifaceted ones that recognize various limits on supply, broader ecological and social values of water, and the costs and efficiency of human use. Nexus approaches are emerging that identify and respond to the way in which water is linked to other resources, such as energy, food and forests. Wealth quintile Poorest quintile Richest quintile Urban 20 40 60 80 100 0 20 40 60 80 100 Environmental inequalities are largely a choice, made by those with the power to choose. Remedying them is also a choice Economic production systems, demographic trends and climate change are all playing big parts in this shift. Over the past two decades, for example, the spread of sophisticated precision irrigation technology has improved efficiency of water use in agriculture. Modern technologies are also transforming wastewater treatment and reuse, as well as the economic viability of seawater desalination. Smart water meters and improved water pricing policies can both improve efficiency. They reflect the way economic and political power-and the intersection of the two-is distributed and wielded, both across countries and within them. Often, these environmental inequalities and injustices are the legacy of entrenched gradients in power going back decades; for climate change, centuries. Countries and communities with greater power have, consciously or not, shifted some of the environmental consequences of their consumption onto poor and vulnerable people, onto marginalized groups, onto future generations. It has underpinned development trajectories that are directly linked to the climate crisis. Technology, in the form of renewables and energy efficiency, offers a glimpse that the future may break from the past-if the opportunity can be seized quickly enough and broadly shared. The way people grapple with these and other technologies so that they encourage, rather than threaten, sustainable and inclusive human development is the subject of the following chapter on technology. The uptake and broad diffusion of climate-protecting technologies old and new will be critical in charting new development paths for all countries. But much more on the policy front needs to be done urgently, with developed and developing countries working together, to avoid dangerous climate tipping points and to ensure that poor and vulnerable people are not left behind. Chapter 7, which takes a panoramic look at policy options across the Report, discusses some potential policies that help address climate change and inequality together in the hope that they help countries chart their paths for more sustainable, more inclusive human development. Historical development paths have exacted environmental and social tolls that are too great. They must change, and there are encouraging signs that they are Chapter 5 Climate change and inequalities in the Anthropocene 193 Spotlight 5. The study found significant spatial heterogeneity in agricultural yields and all-cause mortality. Projected economic impacts varied widely across counties, from median losses exceeding 20 percent of gross county product to median gains exceeding 10 percent. Negative economic impacts were concentrated in the South and Midwest, while the North and West showed smaller negative impacts-or even net gains. The study concluded that climate change will worsen inequality in the United States because the worst impacts are concentrated in regions that are already poorer on average. Effects in the richest third are projected to be less severe, ranging from damages of 6. The study does not address one of the main coping mechanisms for climate change: migration. Migration would affect national impact estimates as well as the absolute costs and benefits for individual counties. In theory, migration could also dampen the impact on inequality, as those experiencing the most negative impacts move to areas less affected and with more opportunities. The United States has a long history of migration for economic opportunity, including in times of environmental and economic crisis (such as the Dust Bowl). It also suggests that migration as a coping mechanism for climate change is less common in poorer countries than in richer ones. Granular analyses, adapted for differences in data availability and quality, could be useful in other contexts. They could also be linked to deprivation and vulnerability data so that climate exposure, impacts and vulnerabilities could be brought together, superimposed and integrated for policy-relevant analysis and visualization, perhaps using geographic information systems. Vulnerability hotspots could be identified-spatially and by population-for policy action, including through impact mitigation and resilience building. Granular analyses would also be key in developing place-specific adaptation pathways, which could advance climate change adaptation, structural inequality reduction and broader Sustainable Development Goal achievement by "identifying local, socially salient tipping points before they are crossed, based on what people value and tradeoffs that are acceptable to them. In a literature review in four climate-change journals through 2012, 70 percent of published studies articulated climate change itself as the main source of vulnerability, while less than 5 percent engaged with the social roots of vulnerability. Different patterns of inequality may emerge at different scales and depending on the kind of inequality being measured. The impact on inequalities at those different levels depends critically on whether more negative impacts are disproportionally borne by those on the lower ends of existing inequality distributions-that is, those already experiencing various forms of greater deprivation or development deficits. A series of studies referenced in the special report indicates that children and the elderly are disproportionally affected by climate change and that it can increase gender inequality. The special report also cites a 2017 report that claims that by 2030, 122 million additional people could become extremely poor, due mainly to higher food prices and worse health. The poorest 20 percent across 92 countries would suffer substantial income losses. Lower-income countries are projected to experience disproportional socioeconomic losses from climate change, placing pressure towards greater inequality between countries and countering prevailing trends of recent decades towards less inequality between countries. A climate change axiom is that wetter Some worsening of inequality due to climate change is already "baked in. Flood frequencies are expected to double for 450 million more people in flood-prone areas. Poor people are expected to be more exposed to droughts for warming scenarios above 1. There certainly is historical precedent for technological revolutions to carve deep and persistent inequalities. The Industrial Revolution may have set humanity on a path towards unprecedented improvements in well-being. But it also opened the Great Divergence,1 separating societies that industrialized,2 producing and exporting manufacturing goods, from many that depended on primary commodities well into the middle of the 20th century. The digitalization of information and the ability to share information and communicate instantaneously and globally have been building over several decades, as with computers, mobile phones and the internet. The 2001 Human Development Report considered how to make these and other new technologies work for human development, focusing on their potential to benefit developing countries and poor people. But recent advances in technologies such as automation and artificial intelligence, as well as developments in labour markets over the course of the 21st century, show that these technologies are replacing tasks performed by humans-raising with heightened urgency the question of whether technology will give rise to a New Great Divergence. Given only the rules, it taught itself how to win-not only at chess but also at Go and Shogi. It interacts with digital technologies in ways that are reshaping knowledge-based labour markets, economies and societies. East Asian countries are investing heavily in artificial intelligence and in advances in its use (discussed later in the chapter). And African countries have seized the potential of mobile phones to foster financial inclusion. Basic artificial intelligence algorithms meant to increase the number of clicks in social media have led millions towards hardened extreme views. In China artificial intelligence enables online lenders to make decisions on loans in seconds, with new credit granted to more than 100 million people. Technology has always progressed in every society, creating disruptions and opportunities (from gunpowder to the printing press). But the advances were typically one-off and did not translate into the sustained and rapid progress18 that Simon Kuznets described as "modern economic growth. This implies that it takes time for the productive use of technology to settle, because it requires complementary changes in economic and social systems. At a minimum another Great Divergence should be avoided while simultaneously addressing the climate crisis. Investments in artificial intelligence need not simply automate tasks performed by humans; they can also generate demand for labour. For example, artificial intelligence can define more detailed and individualized teaching needs and thus generate more demand for teachers to provide a wider range of education services. The direction of technological change involves many decisions by governments, firms and consumers. The cleavages that may open are not necessarily between developed and developing countries or between people at the top and people at the bottom of the income distribution. North America and East Asia, for instance, are far ahead in expanding access to broadband internet, accumulating data and developing artificial intelligence. The chapter describes how some aspects of technology are associated with the rise of some forms of inequality-for instance, by shifting income towards capital and away from labour and the increasing market concentration and power of firms. It concludes that technology can either replace or reinstate labour-it is ultimately a matter of choice, a choice not determined by technology alone. Inequality dynamics in access to technology: Convergence in basic, divergence in enhanced A refrain throughout this Report is that despite convergence in basic capabilities, gaps remain large in enhanced capabilities-and are often widening. To be sure, this is only a partial perspective, given the inequalities in leveraging new technologies, having a seat at the table in the development of these technologies and being trained or reskilled for working with them. In fact, the ability to access and use digital technologies has a defining role both in the pattern of production and consumption and in how societies, communities and even households are organized. More and more depends- to a great extent-on the ability to connect to digital networks. But digital gaps can also become barriers not only in accessing services or enabling economic transactions but also in being part of a "learning society.

Beginning with a cross-sectional study muscle relaxant pain reliever 500mg mefenamic free shipping, the participants are retested after a period of years muscle relaxant kidney stones purchase 500 mg mefenamic amex, providing longitudinal data on these cohorts back spasms 36 weeks pregnant generic mefenamic 500 mg with amex. At the time of this second assessment spasms rib cage area order 250 mg mefenamic otc, a new cross-sectional sample is recruited who are the same age as members of the first sample muscle relaxant india mefenamic 500mg on-line. The process is repeated every 5 or 10 years muscle relaxant india discount 250mg mefenamic with mastercard, continually retesting the longitudinal waves and adding new cross-sectional groups. A second sample added in 1963 ranged between ages 21 and 74; a third sample added in 1970 was ages 21 to 84; a total of seven samples have been recruited to date. At each time of measurement, another sample is recruited, adding participants until the sample now consists of more than 5,000 adults; some have been followed for 35 years. However, longitudinal comparisons present a more optimistic view, with many mental abilities continuing to increase until the mid-50s. Cross-sectional studies create a bias against older adults because of cohort differences in intelligence that are not age-related. D sing a sequential design, Schaie is able to separate effects due to confounds of age, time of measurement, and cohort by treating them as independent variables in his analyses. Williams & Klug, 1996), his work has been extremely influential, contribut- Tested in 1956 Tested in 1963 Tested in 1970 Tested in 1977 Tested in 1984 Tested in 1991 Sample 1 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 3 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 3 Sample 4 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 3 Sample 4 Sample 5 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 3 Sample 4 Sample 5 Sample 6 Figure 9. For example, a sequential approach was used to study the effects of poverty (Bolger, Patterson, & Thompson, 1995) precisely because most research in this area is limited by its cross-sectional nature. By using a sequential design following three cohorts of Black and White students for 3 years, Bolger et al. Skinner (1953) on reinforcement schedules, and it is often seen in applied and clinical settings when behavior modification techniques are used. However, the techniques and logic of single-subject experiments can be readily applied to other research areas. Single-subject experiments (or n = 1 designs) study only one subject-but the subject can be one person, one classroom, or one city. The goal of single-subject experiments is to establish a functional relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable such that changes in the dependent variable correspond to presentations of the independent variable. The treatments are usually some type of reinforcement, such as a smile, praise. The problem, however, is that there could be many reasons for the change other than the experimental treatment. For example, some other event may have coincided with the introduction of the treatment. The single-subject designs described in the following sections address this problem. Reversal Designs the basic issue in single-subject experiments is how to determine that the manipulation of the independent variable has an effect. Next, the independent variable is introduced in the treatment (B) period, and behavior is observed again. Then, the treatment is removed in a second baseline (A) period, and behavior is observed once more. The number of minutes spent studying can be observed each day during the first baseline (A) control period. Then a reinforcement treatment (B) would be introduced in which the adolescent earns the right to watch a certain amount of television for every half hour of schoolwork. Later, this treatment would be discontinued during the second baseline (A) period. First, a single reversal is not extremely powerful evidence for the effectiveness of the treatment. The upcoming test might actually have motivated the student to study more, so the increased study time is not necessarily related to the treatment. The second presentation of B is a built-in replication of the pattern of results seen with the first presentation of B. This sequence ends with the treatment rather than with the withdrawal of the treatment. Multiple Baseline Designs It may have occurred to you that a reversal of some behaviors may be impossible or unethical. An alternative approach is the multiple baseline design, in which multiple measures over time can be made before and after the manipulation. In a multiple baseline design, the effectiveness of the treatment is demonstrated when a behavior changes only after the manipulation is introduced. Such a change must be observed under multiple circumstances to rule out the possibility that other events are responsible for the change in behavior. There are several variations of the multiple baseline design (Barlow & Hersen, 1984). In the multiple baseline across subjects, the behavior of several subjects is measured over time. Note that introduction ofthe manipulation was followed by a change in behavior for each subject. However, because this change occurred across individuals and because the manipulation was introduced at a different time for each student, we can rule out explanations based 149 on chance, historical events, and so on. This type of approach has been used to combat fear of dental procedures in autistic children (Luscre & Center, 1996). Using anti-anxiety treatment, Luscre and Center were able to help three boys (ages 6 and 9 years) tolerate the procedures involved in a dental exam. In a multiple baseline across behaviors, several different behaviors of a single subject are measured over time. Demonstrating that each behavior increased when the reward system was applied would be evidence for the effectiveness of the manipulation. This approach was used to improve the morning routine of a 12-year-old boy with developmental disabilities getting ready for school, a challenge for most parents and children (Adams & Drabman, 1995). The third variation is multiple baseline across situations, in which the same behavior is measured in different settings. The eating behaviors of an anorexic teen can be observed both at home and at scpool. The manipulation is introduced at a different time in each setting, with the expectation that a change in the behavior in each situation will occur only after the manipulation. Single-Subject Designs Problems With Single-Subject Designs One obvious objection to single-subject designs is the small sample. When relying on only one participant, external generalizability may be hard to establish, even when reversals and multiple baselines are employed. Replications with other subjects might extend the findings somewhat, yet even that would be a small sample by social science standards. However, many researchers who use single-subject designs are not interested in generalizing; the primary purpose of single-subject designs is to alter the behavior of a particular individual who presents a problem behavior. A second issue relates to the interpretation of results from a single-subject experiment. Traditional statistical methods are rarely used to analyze data from single-subject designs. If the treatment has a reliable effect on the behavior (diminishing undesirable behavior or increasing desirable behavior), the connection should be evident without a formal statistical analysis. Reliance on such subjective criteria can be problematic because of the potential for lack of agreement on the effectiveness of a treatment. For information on more objective methods of statistical evaluation, refer to Kratochwill and Levin (1992). Despite this tradition of single-subject data presentation, however, the trend increasingly has been to study larger samples using the procedures of singlesubject designs and to present the average scores of groups during baseline and treatment periods. For example, the manipulation may be effective in changing the behavior of some subjects but not others. A final limitation is that not all variables can be studied with the reversal and multiple baseline procedures used in single-subject experiments. Specifically, these procedures are useful only when the behavior is reversible or when one can expect a relatively dramatic shift in behavior after the manipulation. Nevertheless, single-subject studies represent an important, if specialized, method of research. Applications for Education and Counseling Single-subject designs are popular in applied educational, counseling, and clinical settings for assessment and modification of behavior. A counselor treating a client wants to see if the treatment is effective for that particular person. If a student is excessively shy, the goal of treatment is to decrease shyness in that one student. In the classroom, a teacher working with a highly distractible child wants to find an effective treatment for that individual. Single-subject designs are also effective when treating a group, such as a classroom or a community. A teacher may institute a token economy for the entire class to increase the number of books children read. The school community may implement a program of differential reinforcement to increase parental involvement in school activities. One example is a study byJohnson, Stoner, and Green (1996) that tested the effectiveness of three interventions to reduce undesired behaviors and increase desired behaviors in the classroom. Using three different seventhgrade classes, the multiple baseline design found that active teaching of the classroom rules was the most effective method. The key to successful implementation of a behavior modification program is to identify a reinforcer that is rewarding for that particular individual. Children and adults respond differentially for various categories of rewards-tangible and intangible. The use of reinforcers for appropriate behavior provides a good alternative for controlling behavior in the classroom without relying on aversive techniques such as punishment or time-out. In the cross-sectional design, participants of different ages are studied at a single point in time. This method is time-efficient and eco-, I 1[S1 nomical, yet the results may be limited by cohort effects. Groups with substantially similar characteristics are called cohorts, and they are most commonly defined on the basis of biological age. Researchers wishing to study biological age differences must be aware of possible cohort differences between groups, which have nothing to do with age per se. These cohort differences are a possible source of experimental confounding in cross-sectional research. Longitudinal studies test the same participants at two or more points in time, thus avoiding cohort differences. The primary advantage of the longitudinal method is that the researcher can observe developmental changes in the participants by tracking the same individuals over time. Disadvantages of longitudinal research include expense, attrition, and other problems associated with the amount of time needed to complete a longitudinal study. Sequential designs combine cross-sectional and longitudinal approaches in one study. The sequential approach is appropriate for many life span issues in human development. Single-subject experiments are a special class of research designs that typically involve only one participant. The goal of single-subject experiments is to demonstrate a reliable connection between the independent variable and the dependent variable. The basic design involves systematically presenting and withdrawing the independent variable and observing changes in the dependent variable. A multiple baseline design is used when reversal of the target behavior is not possible or is unethical. Multiple baseline designs are used to compare the same behavior across different individuals, different behaviors of one person, and the behavior of one person in different situations. Single-subject experimental designs are useful in educational, counseling, and clinical settings to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions that rely on behavior modification. Why do cross-sectional designs describe developmental differences but not developmental change Explain how attrition of participants in a longitudinal study can produce systematic bias in the results as the study progresses. Distinguish between multiple baseline designs across subjects, across behaviors, and across situations. Mter the investigator selects an idea for research, many practical decisions must be made before participants are contacted and data collection begins. In this chapter we examine some of the general principles researchers use when planning the details of their studies. Review the ethical guidelines for working with children and adults before you conduct your study. It is extremely important to prevent psychologicalor physical harm to the participants. According to ethical guidelines, you may not even test participants until your project has ethical approval from your Institutional Review Board. You also have an ethical responsibility to treat participants with courtesy and respect. In turn, you should take care to allot sufficient time to provide complete explanations for any questions participants may have. Although it is tempting to be more "efficient" by testing participants rapidly, it is unwise to rush through the initial greeting, the experimental procedures, or the debriefing at the end of the session. Researchers must also be extremely careful about potential invasion of privacy and are responsible for protecting participant anonymity. Keep these issues in mind when designing your study to ensure that you conduct an ethical investigation. The method used to select participants has implications for generalization of the research results.

Buy cheap mefenamic 500 mg line. Icy hot review dollar tree/Walgreens.

References