|

STUDENT DIGITAL NEWSLETTER ALAGAPPA INSTITUTIONS |

|

Jennifer McNulty, MD

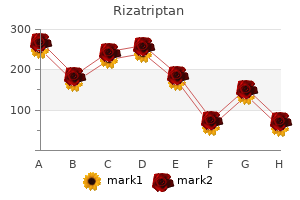

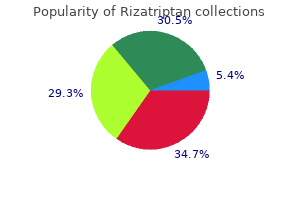

Table 5 lists the different responses seen with central or peripheral lesions for the Nylen-Barany maneuver home treatment for shingles pain cheap 10 mg rizatriptan amex. No May change direction Slight More than one position Hyperactive responses florida pain treatment center purchase rizatriptan 10mg with amex, impaired fixation pain solutions treatment center hiram 10mg rizatriptan with mastercard, suppression Latency period before onset of nystagmus Duration of nystagmus Fatigability Direction of nystagmus in one head position Vertigo intensity Head positions eliciting vertigo Caloric and rotary tests Glossopharyngeal and Vagus Nerves these nerves are usually tested together since they have overlapping functions sciatica pain treatment youtube purchase 10 mg rizatriptan mastercard. The glossopharyngeal nerve primarily carries sensation from the posterior pharynx and the larynx pain treatment for burns order rizatriptan 10mg without prescription. The vagus nerve supplies motor innervation to the soft palate pain treatment for sciatica buy 10 mg rizatriptan visa, pharyngeal muscles and the vocal cords. The vagus nerve is easily tested by asking the patient to phonate and observing for a symmetric rise in the palate and uvula. In this test, the examiner touches the posterior pharyngeal wall with a tongue blade and observes for a symmetric rise in the palate and uvula. The afferent arm of this reflex is carried by the glossopharyngeal nerve and the efferent arm by the vagus nerve. Sternocleidomastoid function is assessed by asking the patient to rotate the head against resistance. A lesion of the hypoglossal nerve will eventually cause atrophy of the ipsilateral half of the tongue. Recall that the tongue will also deviate towards the side of the lesioned nerve when protruded. Cranial Nerve Reflexes Practically the entire brain stem can be evaluated by means of five cranial nerve reflexes. This is extremely useful in evaluating the cause of coma in an unresponsive patient. Another important distinction in the evaluation of weakness is whether the weakness has a characteristic "upper motor neuron pattern" or "lower motor neuron pattern". The motor examination consists of several parts: assessment of muscle bulk, evaluation of muscle tone, observation for spontaneous movements, and functional and formal muscle strength testing. Muscle Bulk In general, muscle bulk should be symmetric throughout the limbs, when comparing the right and left sides, and proximal and distal portions of the extremities. Disuse atrophy: A mild form of muscle atrophy that can be seen in a variety of clinical settings, including upper motor neuron disease, disuse, corticosteroid use, collagenvascular disorders, and with musculoskeletal problems. Myoclonus: Sudden contractions of a muscle or group of muscles that move an entire limb across a joint. Chorea and Athetosis: Brief, irregular, asymmetric writhing movements of basal ganglia origin. Chorea is a quick, distal dance-like movement and athetosis is a more proximal slower movement. Tremor: A rhythmic, oscillatory movement of the trunk or limbs due to numerous causes, including lesions of the cerebellum, motor system, sensory system or the basal ganglia. Action tremor can be seen with lesions of the cerebellum or the sensory system, and may also be idiopathic (benign familial tremor or senile tremor). Tone may be increased or decreased in various pathologic states, and various forms of altered muscle tone are detailed in table 7. Functional Testing Functional testing is a very reliable form of testing muscle strength that is easily reproducible and reflects the ability of the patient to perform certain tasks. This test is performed by having the patient hold both hands outstretched with the palms up and the eyes closed. The examiner watches for subtle pronation of the arm, which sometimes is accompanied by abduction and internal rotation at the shoulder and flexion at the elbow. Pronation of the arm is a subtle sign that is strongly indicative of upper motor neuron dysfunction. Formal Testing Formal muscle strength testing involves grading muscle strength for individual muscle groups on a 0-5 scale by means of push/pull testing by the examiner. Representative muscle groups that are often evaluated in a screening examination are listed in table 8. The sensory examination is largely a subjective examination that requires an alert, cooperative patient who can give reliable subjective impressions of various stimuli. In general, sensory symptoms precede sensory signs, and the sensory examination may not be revealing early on in the course of an illness that produces sensory dysfunction. In general, the examiner looks for a proximal-to-distal gradient, or for findings in the distribution of a specific nerve or nerve root. The sensory examination is divided into three parts: primary modalities, cortico-sensory modalities, and functional testing (the Romberg test). Primary Modalities Protopathic sensation Examples of protopathic sensation include poorly localized touch, pain and temperature perception. These modalities are carried by small, unmyelinated fibers, travel contralaterally in the lateral spinothalamic tracts in the spinal cord, and are ultimately processed in the brain stem reticular formation and in the thalamus. The "prickly" sensation may be reported by the patient as diminished, absent or heightened in the affected areas. Temperature: this can be assessed with a cool tuning fork, or with test tubes filled with cold or hot water. Epicritic sensation Examples of epicritic sensation include fine, discriminative touch, vibration, and proprioception (position sense). These modalities are generally subserved by encapsulated nerve endings and are carried by large, myelinated nerve fibers, ascending ipsilaterally in the dorsal columns in the spinal cord. This information then crosses in the medulla, projects to the thalamus and is ultimately processed in the primary sensory cortex. If vibratory perception is absent distally, more proximal joints are assessed in a similar fashion. Cortico-sensory Modalities these are more complex forms of sensation that require significant cortical processing. Four different cortico-sensory modalities are typically evaluated: stereognosis, graphesthesia, twopoint discrimination, and double simultaneous stimulation. To evaluate this modality, objects such as a safety pin or coin are placed in the hand of a patient for identification. Two Point Discrimination: the ability to localize and discriminate between two points that are close together. This is typically tested on the tip of the index finger with a paper clip that is bent open. The examiner applies both ends of the clip, keeping them several millimeters apart and moving them closer and closer together. Normal subjects have a detection threshold of 2 mm at the tip of the index finger. Double Simultaneous Stimulation: A normal subject should be able to localize two stimuli that are applied simultaneously to different parts of the body. Patients with a parietal lobe lesion have a phenomenon known as extinction in which they consistently fail to identify a stimulus on the side of the body contralateral to a parietal lobe lesion, when it is presented simultaneously with a stimulus on the opposite side of the body. In a broad sense, extinction to double simultaneous stimuli is a type of agnosia known as sensory neglect. To test for extinction, the right and left sides of the body are touched at the same time and the patient is asked to localize both stimuli with the eyes closed. This test is performed by asking the patient to stand with his/her feet together and then close the eyes. The patient is then observed to see if balance can be maintained with the eyes closed. Recall that three systems are routinely used to maintain balance, namely proprioception, the vestibular apparatus and vision. If balance is maintained with the eyes closed, this implies integrity of both the vestibular apparatus and proprioception. The Romberg test can only be performed if the patient is able to stand well with feet together and eyes open. If the patient cannot do this well, a lesion of the cerebellum is suspected; the Romberg test cannot be performed under these circumstances. Tests of coordination typically assess cerebellar function, but the contributions of the other systems, including the motor, sensory and vestibular systems, must be considered when interpreting these tests. Coordination testing is usually divided into two parts: truncal stability and limb coordination. The ability to check movements and vestibular coordination are also assessed if the clinical situation warrants. Heel-to-Shin Test: the heel of one leg is run smoothly down the other shin, and speed, accuracy and any tremor are noted. Foot tapping is a rapid alternating movement frequently evaluated in the lower extremity. Ataxia and dysmetria are general terms used to describe unevenness in the performance of any of the above tests, and are frequently due to lesions involving the cerebellar hemispheres. Recall that cerebellar lesions produce ataxia on the side ipsilateral to the lesion. Upper motor neuron lesions or sensory lesions that result in altered proprioception can also result in ataxia and dysmetria. Ability to Check Movements Ability to check movements is evaluated by asking the patient to maintain flexion of his/her arm at the elbow against resistance provided by the examiner. An inability to check movements can be seen with lesions of the ipsilateral cerebellar hemisphere, as well as with severe sensory disturbances causing altered proprioception. Rotation of the body in one direction is suggestive of ipsilateral vestibular pathology. Not only are reflexes helpful in evaluating awake individuals, but they also are invaluable in examining comatose patients. The non-pathologic reflexes include muscle stretch reflexes (deep tendon reflexes) and superficial (cutaneous) reflexes. The pathologic reflexes include the Babinski sign as well as the frontal release signs. Muscle Stretch Reflexes Muscle stretch reflexes are monosynaptic spinal cord reflexes that are elicited by striking the muscle tendon with a percussion hammer and evaluating the subsequent contraction of that muscle. Striking the muscle tendon stretches the muscle spindle and this afferent information is carried by the Ia afferent sensory nerve fibers through the dorsal root and dorsal horn of the spinal cord, eventually synapsing on a corresponding anterior horn cell in the ventral horn of the spinal cord. The efferent arm of this reflex originates in the anterior horn cell, exits the spinal cord in the ventral root, and is carried by the alpha motor neuron, eventually synapsing on the same muscle. Five muscle stretch reflexes are usually elicited in a routine neurologic examination, and these are listed in table 10. Ankle clonus is easy to obtain in a 34 hyperreflexic patient, and can be elicited by sudden dorsiflexion of the foot. Patellar clonus can be obtained by a quick, downward motion on the patella, holding the knee slightly flexed. Superficial (Cutaneous) Reflexes Superficial (cutaneous) reflexes are polysynaptic, nociceptive reflexes that are elicited by stimulating the skin and observing for contraction of the corresponding muscle. Four superficial reflexes can be easily obtained: the abdominal reflexes, the anal wink reflex, the cremasteric reflex and the bulbo-cavernosus reflex. The upper quadrants reflect T6-9 innervation and the lower quadrants T10-12 innervation. Abdominal reflexes may be diminished or absent in many circumstances, including a lesion to the corresponding nerve roots or with upper motor neuron lesions. In addition, obesity, previous pregnancy or abdominal surgery can result in a loss of abdominal reflexes. The anal wink reflex is elicited by stroking the perianal skin and observing for a contraction of the external anal sphincter on the stroked side. The cremasteric reflex is elicited by stroking the skin on the inner thigh in a male and observing for elevation of the testicle on the stroked side. The bulbo-cavernosus reflex is elicited by squeezing the glans penis and observing for contraction of the external anal sphincter. An abnormal (positive) response consists of dorsiflexion of the great toe, and occasionally fanning of the other toes. Four frontal release signs are commonly tested: snout, palmomental, grasp and glabellar reflexes. One way of eliciting this reflex is to place a tongue blade lightly over the upper lip and to tap the tongue blade with a percussion hammer. Glabellar Sign: this is elicited by tapping the forehead repeatedly between the eyebrows over the glabella and observing for persistent blinking. It is important to note that a normal individual will blink once or twice only with this maneuver. Particular attention is placed on any asymmetry involving a side or one limb, the distance the feet are kept apart (base), the length of stride and associated arm swing. An important part of the gait examination is to observe a tandem gait, in which the patient is asked to walk heel-to-toe on a line. This narrows the base of the gait and will bring out subtle gait abnormalities that may not be otherwise evident. Inability to perform a tandem gait is frequently associated with altered proprioception or midline cerebellar lesions. When evaluating gait, the examiner first notes if the gait is symmetric or asymmetric. Various abnormal gaits, including asymmetric gaits and wide-based and narrow-based symmetric gaits are detailed in table 12.

Physical examination shows small pupils best pain medication for old dogs buy rizatriptan 10 mg free shipping, cracked lips pain disorder treatment plan cheap 10mg rizatriptan otc, and bruises and scratches over the upper extremities gallbladder pain treatment diet discount rizatriptan 10mg free shipping. Mental status examination shows mild obtundation stomach pain treatment natural rizatriptan 10mg fast delivery, blunted affect pain management for dogs after neutering quality rizatriptan 10 mg, and slow pain treatment and wellness center greensburg pa order 10mg rizatriptan otc, incoherent speech. A healthy 9-year-old boy is brought to the physician by his parents because they are concerned that he dislikes attending school. He misses school at least 1 day weekly because his mother is exhausted from fighting with him to attend. At home, he tends to stay in the same room as his mother and will sometimes follow her around the house. When his parents plan an evening out, he often becomes tearful and asks many questions about when they will return. He makes brief eye contact and speaks in a low volume, becoming tearful when questioned about being away from his mother. A 47-year-old woman is brought to the physician by her husband because of bizarre behavior for 1 week. Her husband says that she makes no sense when she speaks and seems to be seeing things. She also has had difficulty sleeping for 2 months and has gained approximately 9 kg (20 lb) during the past 5 months. He also notes that the shape of her face has become increasingly round and out of proportion with the rest of her body despite her weight gain. Physical examination shows truncal obesity and ecchymoses over the upper and lower extremities. Mental status examination shows pressured speech and a disorganized thought process. One day after admission to the hospital for agitation and hallucinations, a 19-year-old man has the onset of severe muscle stiffness that prevents him from rising out of bed. Physical examination shows generalized severe rigidity of the upper extremities bilaterally. A 32-year-old woman comes to the physician because of a 3-week history of depressed mood. She says that she has always had a busy schedule, but lately she has not had her usual amount of energy and has had difficulty getting up and going to work. She describes herself as normally a "hyper" person with energy to perform multiple tasks. During the past 10 years, she has had similar episodes in which she has had depressed mood associated with a decreased energy level that makes her feel "slowed down. She sometimes goes through periods when she feels a surge in energy, sleeps very little, feels at the top of her mental powers, and is able to generate new ideas for the news station; these episodes never last more than 5 days. She says that she loves feeling this way and wishes the episodes would last longer. A 77-year-old woman is brought to the emergency department by her husband because of agitation and confusion for 3 hours. He states that she has been intermittently crying out and does not appear to recognize him. A routine health maintenance examination 3 days ago showed no abnormalities except for mild memory deficits. Physical examination shows no abnormalities except for mild tenderness to palpation of the lower abdomen. Mental status examination shows confusion; she is oriented to person but not to time or place. A 14-year-old boy is brought to the physician by his mother after she found an unsmoked marijuana cigarette in his bedroom. When interviewed alone, the patient reports that his friends heard about smoking marijuana and acquired some from their peers to find out what it was like. He requests that his teachers not be informed because they would be very disappointed if they found out. On mental status examination, he is pleasant and cooperative and appears remorseful. An otherwise healthy 27-year-old man is referred to a cardiologist because of three episodes of severe palpitations, dull chest discomfort, and a choking sensation. The episodes occur suddenly and are associated with nausea, faintness, trembling, sweating, and tingling in the extremities; he feels as if he is dying. Within a few hours of each episode, physical examination and laboratory tests show no abnormalities. A 42-year-old woman is brought to the physician by her husband because of persistent sadness, apathy, and tearfulness for the past 2 months. She has a 10-year history of systemic lupus erythematosus poorly controlled with corticosteroid therapy. Physical examination shows 1-cm erythematous lesions over the upper extremities and neck and a malar butterfly rash. A 27-year-old man is brought to the emergency department by police 2 hours after threatening his next door neighbor. Three months ago, he noticed that his neighbor installed a new satellite dish and says that since that time, she has been watching every move he makes. He has not had changes in sleep pattern and performs well in his job as a car salesman. A 9-year-old girl is brought to the physician by her adoptive parents because they are concerned about her increasing difficulty at school since she began third grade 7 weeks ago. Her teachers report that she is easily frustrated and has had difficulty reading and paying attention. She also has had increased impulsivity and more difficulty than usual making and keeping friends. Her biologic mother abused multiple substances before and during pregnancy, and the patient was adopted shortly after birth. The most likely explanation for these findings is in utero exposure to which of the following A 77-year-old man comes to the physician with his daughter for a follow-up examination to learn the results of neuropsychological testing performed 1 week ago for evaluation of a recent memory loss. Results of the testing indicated cognitive changes consistent with early stages of dementia. Three weeks ago, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and has shown signs of a depressed mood since then. Twenty years ago, he required treatment in a hospital for major depressive disorder. His symptoms resolved with antidepressant therapy, and he has not taken any psychotropic medication for the past 15 years. She says she is concerned about what the results might be and how her father will handle them. Which of the following is the most appropriate initial physician statement to this patient A 52-year-old woman with glioblastoma multiforme in the frontal lobe tells her physician that she does not want operative treatment. She is mentally competent and understands that an operation is the only effective treatment of her tumor, and that without an operation she will die. She is afraid of the adverse effects of an operation and says she has lived a long and happy life. Two weeks later, she lapses into a coma, and her husband requests that the operation be carried out. Which of the following is the most appropriate consideration for her physician in deciding whether to operate Ten years ago, a 60-year-old woman underwent an aortic valve replacement with a porcine heterograft. A 42-year-old woman comes to the emergency department because of a 2-day history of intermittent lower abdominal pain and nausea and vomiting. Initially, the vomitus was food that she had recently eaten, but it is now bilious; there has been no blood in the vomit. Examination shows a distended tympanitic abdomen with diffuse tenderness and no rebound. A 4-year-old boy is brought to the physician by his parents because of a 4-month history of difficulty running and frequent falls. His parents report that his calves have been gradually increasing in size during this period. His pulse is 130/min, respirations are 8/min and shallow, and palpable systolic blood pressure is 60 mm Hg. A 70-year-old man is admitted to the hospital for elective coronary artery bypass grafting. Ten days after admission to the hospital because of acute pancreatitis, a 56-year-old man with alcoholism develops chills and temperatures to 39. She has had spotty vaginal bleeding for 2 days; her last menstrual period began 7 weeks ago. Examination shows blood in the vaginal vault and diffuse abdominal tenderness; there is pain with cervical motion. A 52-year-old man comes to the physician because of a 5-month history of pain in his left knee that is exacerbated by walking long distances. His pulse is 82/min and regular, respirations are 16/min, and blood pressure is 130/82 mm Hg. Examination of the left knee shows mild crepitus with flexion and extension; there is no effusion or warmth. X-rays of the knees show narrowing of the joint space in the left knee compared with the right knee. A previously healthy 32-year-old man comes to the emergency department because of a 3-day history of pain and swelling of his right knee. Two weeks ago, he injured his right knee during a touch football game and has had swelling and bruising for 5 days. A 57-year-old woman with inoperable small cell carcinoma of the lung has had lethargy, loss of appetite, and nausea for 1 week. A 3799-g (8-lb 6-oz) female newborn is born by cesarean delivery because of a breech presentation. Initial examination shows a palpable clunk when the left hip is abducted, flexed, and lifted forward. A previously healthy 72-year-old man comes to the physician because of decreased urinary output during the past 2 days; he has had no urinary output for 8 hours. His serum urea nitrogen concentration is 88 mg/dL, and serum creatinine concentration is 3. A 3-year-old boy is brought to the emergency department because of a 2-week history of persistent cough and wheezing. An expiratory chest x-ray shows hyperinflation of the right lung; there is no mediastinal or tracheal shift. Two hours after undergoing a right hepatic lobectomy, a 59-year-old woman has a distended abdomen. Three days after undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis, a 42-year-old woman has the onset of hematomas at all surgical sites. She was treated for deep venous thrombosis 3 years ago but was not taking any medications at the time of this admission. Prior to the operation, she received heparin and underwent application of compression stockings. Acute intermittent porphyria Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia Hypersplenism Inhibition of cyclooxygenase von Willebrand disease Two days after undergoing surgical repair of a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, a 67-year-old man requires increasing ventilatory support. A previously healthy 62-year-old man comes to the physician because of a 2-month history of cough. Fasting serum studies show a total cholesterol concentration of 240 mg/dL and glucose concentration of 182 mg/dL. A 3-year-old girl is brought to the emergency department because of left leg pain after falling at preschool 2 hours ago. She has consistently been at the 10th percentile for height and weight since birth. An x-ray shows a new fracture of the left femur and evidence of previous fracturing. An 83-year-old man who is hospitalized following transtibial amputation for treatment of infected diabetic foot ulcers develops pneumonia and sepsis. His only living relatives are his sister, who has severe dementia and resides in a local nursing care facility; his niece, who visits him regularly; and his brother, from whom he is estranged and who does not want any involvement in his care. It is most appropriate for which of the following people to make end-of-life care decisions on behalf of this patient A family physician in a town located more than 20 miles from the nearest hospital chooses to discontinue traveling to hospitals where his patients are admitted to perform the duties of attending physician. A 40-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus asks his physician what the likelihood is for development of peripheral neuropathy if the patient continues to smoke. Which of the following is the most appropriate study design to determine this prognosis Prior to discharge from the hospital, patients admitted for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease receive smoking cessation counseling. On discharge, the pharmacist educates and provides patients with written materials regarding the use of their medications.

Dyslexia in Different Languages and Orthographies How many of the reading problems encountered by individuals with dyslexia are unique to the English language Although most of the language-based deficits described Comorbid Disorders Developmental Dyslexia and Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder It has been suggested that as many as 40% of children with dyslexia also have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 1 wrist pain treatment tendonitis purchase rizatriptan 10 mg overnight delivery. Because these disorders have been seen both alone and together pain treatment with laser cheap 10mg rizatriptan with visa, there has been some debate as to whether they were entirely independent pain management for arthritis in dogs buy 10mg rizatriptan overnight delivery. More recently pain management for dogs with arthritis rizatriptan 10mg overnight delivery, a common etiology to their co-occurrence has been supported by genetic evidence of susceptibility regions on chromosomes 2 pain treatment ulcerative colitis generic rizatriptan 10 mg with visa, 8 pain management senior dogs rizatriptan 10 mg amex, 14, and 15. Separately, either disorder can affect learning or either can affect focus of attention, thus making their independent and collective contributions particularly difficult to identify. Obviously, the importance of correct diagnosing has obvious treatment implications, whether academic, behavioral, or pharmacological. Brain imaging studies support the proposition that phonological deficits and language comprehension are served by different neural networks, further support for independent etiologies. The separate and combined aspects of these often coexisting disorders make it prudent to adopt specific intervention strategies to address their respective deficits, highlighting phonological processes on one hand and listening comprehension on the other. Therapeutic Approaches to Developmental Dyslexia Given the plurality of weaknesses in addition to reading problems that are observed in individuals with dyslexia, the necessity for multiple treatment strategies may seem pressing. As discussed above, programs that emphasize phonological coding are known to facilitate reading acquisition. Although gains in phonological representation can bring about growth in multiple aspects of reading, they do not generalize to all aspects of reading. For example, promoting reading fluency and reading comprehension in addition to phonology requires other types of intervention approaches. Studies targeting domains of reading other than phonological coding, such as orthography, are less numerous. Increasingly, successful treatment methods represent a combination of training approaches (combining phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension), which, although logical from an educational perspective, complicates any experimental approach to identify independent contributors of reading recovery. These observations from the classroom are ripe for neuroscientific inquiry, based on our understanding of neural responses under conditions of single versus multiple sensory stimulation in the auditory and visual systems. Evaluating the benefits of various remediation strategies for dyslexia is beyond the scope of this article; a thorough review of representative therapies has been published by Alexander and colleagues. From the neuroscientific perspective, it is of value to establish the neural correlates of successful reading interventions as these provide important insight not only into brain mechanisms of dyslexia but also into behavioral plasticity. Based on a rich animal and human literature of training-induced brain plasticity and functional reorganization following rehabilitation from cerebral injury, one can consider several paths that would lead to changes following successful reading intervention in developmental dyslexia. One is a mechanism by which brain regions with known anomalies in dyslexia are shown to establish a more typical response. An alternative brain response could involve the manifestation of brain activity in brain regions not typically associated with the reading process. Such compensatory strategies have been described for stroke patients in brain regions contralateral to the injury (and which encompassed the site typically activated by the now relearned skill). Functional brain imaging technology has allowed these models to be subjected to the test. For example, in a study comparing dyslexic adults with persistent reading problems following 120 h of intensive reading intervention to a matched group of dyslexics receiving no intervention at all, the intervention group was found to have increased activity in bilateral parietal and right perisylvian cortex following the intervention (see Figure 5). These results suggest that the significant gains in reading enjoyed by the intervention group could be attributed to right hemisphere compensation combined with increases in a more typically reading-related left hemisphere brain 190 Dyslexia, Neurodevelopmental Basis See also: Language Development; Language, Cortical Processes; Language, Learning Impairments. Neuroanatomical markers for dyslexia: A review of dyslexia structural imaging studies. Specific reading disability: Differences in contrast sensitivity as a function of spatial frequency. Sex differences in developmental reading disability: New findings from 4 epidemiological studies. Specific reading disability (dyslexia): What have we learned in the past four decades Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia, and skilled reading across languages: A psycholinguistic grain size theory. Figure 5 Functional anatomy of phonological manipulation following reading remediation (Group X Session interaction) revealed increases during phonological manipulation in left parietal cortex and fusiform gyrus. Right hemisphere increases included posterior superior temporal sulcus/gyrus and parietal cortex. Several functional brain imaging studies have also been conducted in children receiving reading interventions, and a review of this small literature suggests a role for age (or brain maturation) in directing the pattern of treatmentinduced brain plasticity. This, however, does not mean that changes in brain activity necessarily guarantee behavioral gains, and results from these studies are meaningful only if the studies follow rigorous research practices, such as the use of controlled, randomized experimental designs. Summary Developmental dyslexia has been studied in the context of learning, development, experiential factors, genetic influences, and brain function. For all children, a mastery of reading requires the integration and coordination of sensorimotor and cognitive processes. How these fail to operate at an optimal level to bring about accurate and fluent reading in the context of normal cognitive function and appropriate teaching methods continues to be questioned from the viewpoint of behavior and brain function. Avenues of remediation within both cognitive and sensorimotor domains are under active investigation to establish the efficacy of these approaches as well as to discover their neuronal targets. Investigations into the hereditary mechanisms of reading deficits hold the promise of strengthening the understanding of the neural mechanisms of dyslexia. Together, behavioral and physiological studies continue to aid in the early identification of dyslexia and best avenues for its treatment. Introduction Investigating how the brain accomplishes language comprehension is a particular challenge compared to other areas of cognitive neuroscience. Animal models are of limited value given that no other species has a comparably complex communication system. On the other hand, areas as distinct as sensory physiology and formal linguistics contribute important details to our understanding of language processes in the brain. This work provides a solid foundation upon which to examine cognitive factors and the brain mechanisms involved in the transformation of a low-level signal into the highly complex symbolic system we know as human language. Three major goals of using neuroimaging are to understand where language is processed in the brain and when and how the different levels of linguistic processing unfold in time. We will outline the factors that influence these brain responses, and by inference, the linguistic processes they reflect. Other components reflect integration or revision processes and tend to have larger latencies (up to 1 s). A recent theme that has gained increasing prominence is the degree to which these ``linguistic' components are actually domain specific. Most of them have been described initially as being related to language processes only. However, subsequent research has usually weakened the case for domain specificity. For example, the P600 (Osterhout & Holcomb, 1992) had been linked to syntactic processing. More recently, however, it has been proposed that language and music share processing resources and that a functional overlap exists between neural populations that are responsible for structural analyses in both domains (Patel et al. It might even be proposed that some of them might be more accurately thought of as domain-non-specific responses that reflect basic operations critical for, but not limited to , linguistics processes. Noting the disagreement in the literature as to whether continuous speech stimuli elicit the early sensory components (including the N100), these studies sought to clarify whether word onsets within a context of continuous speech would elicit the early sensory or ``obligatory' components. This work also examined whether the hypothesized word onset responses were related to segmentation and word stress. It was found that word onset syllables elicited larger anterior N100 responses than word medial syllables across all sentence conditions. Thus, word onset effects on the N100 were examined as a function of word stress with the finding that stressed syllables evoked larger N100 responses than unstressed syllables at electrode sites near the midline. Such an effect was expected given the physical differences that exist between stressed and unstressed syllables. However, it was concluded that the N100 was monitoring more than the physical characteristics of the stressed and unstressed syllables because the N100 to these stimuli showed a different scalp distribution compared to that seen for the N100 to word onset and word medial syllables which had been equated for physical characteristics. The conclusion was made that non-native speakers do not use the acoustic differences as part of a speech comprehension system in the same manner as native speakers. It also appears to be related to phonological awareness, responds to single phoneme violations of localized expectations, and is insensitive to phonologically correct pattern masking. Semantically implausible content words in sentence contexts elicit larger centro-parietal N400s (dotted lines) than plausible words (solid lines) between 300 and 600 ms. Exemplar-subordinate probabilities for congruent endings determined high-constraint primes (shallow end) or a low-constraint primes (sunken ship) which primed auditory target words in the paired sentences (in capitals) that were either congruent (Pool/ Ocean) or not (Barn/Marsh). This effect is achieved by having a subject watch a speaker articulate a syllable that differs from what is recorded on the audio channel the subject hears. Lexico-Semantic Integration: the N400 Component this typically centro-parietal and slightly right-lateralized component peaks around 400 ms and was first observed to sentence-ending words that were incongruous to the semantic context of the sentences in which they occurred. More generally, the N400 amplitude seems to reflect costs of lexical activation and/or semantic integration, such as in words terminating low versus high contextually constrained sentences (Connolly et al. Other work has proposed that the N400 is larger to openthan closed-class words and in a developing sentence context becomes progressively smaller to such words as sentence context develops and provides contextual constraints (Van Petten & Luka, 2006). The N400 was also seen with both classes (albeit smaller to closed-class words, as mentioned above, due to their reduced semantic complexity), reinforcing the view that neither component offers support for different neural systems being involved in the processing of word class. N400s have also been shown to be larger to concrete than abstract words and to words with higher density orthographic neighborhoods (Holcomb et al. Word frequency appears to affect N400 amplitude, being larger for low than high frequency words. However, this effect disappears when the words are placed in a sentence context; a finding that has been interpreted as suggesting the N400 word Colin, C. Event-Related Potentials in the Study of Language 195 frequency effect is probably semantically based (Van Petten & Luka, 2006). The issue of domain specificity refers to a recurring theme about whether N400 activation reflects activity in an amodal conceptual-semantic system. Based on earlier work that used line drawings of objects within an associate priming paradigm that required participants to indicate whether they recognized the second item in each pair, McPherson and Holcomb (1999) used color photos of identifiable and unidentifiable objects in three conditions in which an identifiable object preceded a related identifiable object, an unrelated identifiable object, and an unidentifiable object. Replicating earlier work, they found both a negativity at 300 ms as well as an N400 to the unrelated and unidentifiable objects. The N400 exhibited an atypical frontal distribution that was attributed to the frontal distribution of the adjoining negativity at 300 ms. An argument was made that as no equivalent of the N300 had been seen to linguistic stimuli it might be a response specific to objects/pictures. We now know that a similar response is seen to linguistic stimuli but that fact does not invalidate the proposal that the ``N300' may be object/picture specific. In a similar vein, simple multiplication problems in which the answer is incorrect exhibit an N400 that is smaller if the incorrect solution is conceptually related to one of the operands in a manner similar to contextual modulation of the language-related N400 (Niedeggen et al. The explanation of this N400 effect is a combination of activation spread and controlled processing mechanisms. A particularly interesting aspect of this study is that the authors take the position that treating the N400 as a unitary monolithic phenomenon is likely to be incorrect. They divided the N400 component into three sections: the ascending limb, the peak, and the descending tail of the waveform. Having done this, they demonstrate that the ascending limb appears related to automatic aspects of activation spread while the descending limb is associated with the more controlled processing functions. This syntactic parsing of the hierarchical structure of utterances will reveal whether John is the agent of the action, and whether this action is continuing or has been completed. Parsing takes place incrementally in real time at rates of approximately three words per second and involves (1) the analysis of word order and word category information including function words (is, the, was, by) and (2) the checking of certain features that need to be congruent between linked sentence constituents. The rationale is that violations should disrupt or increase the workload of the brain systems underlying the type of processing that is of interest. The qualitative differences between these two components and the semantic N400 have been taken as evidence that syntactic and semantic information are processed differently in the brain (Osterhout & Holcomb, 1992). Amplitude is on left vertical axis, scalp location on bottom axis, and time (ms) on right axis. Despite his apparent vegetative state, the patient exhibited classic N400 responses to the semantically incongruous sentence endings. As expected, they observed an anterior negativity only between 300 and 500 ms which, moreover, was bilaterally distributed rather than left lateralized. Based on word category information alone, the brain has simply no reason to assume an outright syntax violation, unless (a) it either knows in advance that such sentences are not included in the experiment. In this latter case, however, the word category is entirely irrelevant as any single-word completion following am would cause a syntax violation. This appears appropriate for syntactic structures involving long-distance dependencies (such as wh questions) and may, in fact, refer to a distinct set of left anterior negativities. P600 components have been found across languages for a large variety of linguistic anomalies, such as (a) nonpr-preferred ``garden path' sentences that require structural reanalyses due to local ambiguities (Osterhout & Holcomb, 1992; Mecklinger Event-Related Potentials in the Study of Language 199 et al.

Consequently southern california pain treatment center pasadena buy 10 mg rizatriptan with visa, there are two major types of strokes: obstructive (ischemic) and hemorrhagic nerve pain treatment for shingles cheap rizatriptan 10 mg with mastercard. Recovery is observed during the following hours pain medication for a uti purchase 10 mg rizatriptan with visa, days herbal treatment for shingles pain generic rizatriptan 10 mg mastercard, or weeks after the accident upstate pain treatment center buy rizatriptan 10 mg otc. As the results of decreases in edema (swelling) and diaschisis (extended impairment effect due to the broad connectivity of each brain area with the rest of the brain) pain treatment peptic ulcer buy 10mg rizatriptan visa, symptomatology is progressively reduced to focal sequelae. The neurological or Aphasia Handbook 31 neuropsychological residual deficit typically reflects the site and the size of the lesion (Figure 2. Blood goes to the brain through two different systems: the carotid system and the vertebrobasilar system. The first one originates the anterior and middle cerebral arteries, while the second one originates the posterior cerebral artery. Incidence has been estimated as about 80150/100,000 and the prevalence in over 500/100,000. Stroke also is the leading cause of serious, longterm disability in many countries. About 75% of all strokes occur in people over the age of 65 and the risk of having a stroke more than doubles each decade after the age of 55. Percentage of respondents reporting a history of stroke (according to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2010). As a matter of fact, there is a significant correspondence between the territory of the middle cerebral artery and the surrounding brain area relative to language. Cortical territory irrigated by the anterior (blue), middle (red) and posterior (yellow) cerebral arteries. Furthermore, the specific aphasia subtype depends upon the particular branch of the middle cerebral artery that is involved (Table 2. When the main trunk of the left middle cerebral artery is involved, a global aphasia is found; when some specific branches are impaired, more diverse types of language disturbances may be observed. Occlusive (ischemic) Two different conditions can be found relative to ischemic stroke: (1) Embolism: it is the occlusion of a vessel by material floating in arterial system. The emboli are usually formed from blood clots but are occasionally comprised of air, fat, or tumor tissue. Embolic events can be multiple and small, or single and massive; (2) Thrombosis: is the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. Thrombotic and embolic stroke Hemorrhagic Brain hemorrhage is another type of stroke. It is caused by an artery in the brain bursting and causing localized bleeding in the surrounding tissues. Most frequently, it is caused by bleeding from a cerebral aneurysm, but also can be due to bleeding from an arteriovenous malformation or head injury; Injury-related subarachnoid hemorrhage is often seen in the elderly who have fallen and hit their head. Among the young, the most common injury leading to subarachnoid hemorrhage is motor vehicle crashes. Aphasia Handbook 35 (2) Intracerebral hemorrhage: is a type of stroke caused by bleeding within the brain tissue itself. It is most commonly caused by hypertension, arteriovenous malformations, or head trauma. In closed head injury two different possibilities are separated: concussion and contusion. A concussion is a significant blow to the head that temporarily affects normal brain functions and may result in unconsciousness. A concussion may result from a fall in which the head strikes against an object or a moving object strikes the head. It is thought that there may be microscopic shearing of nerve fibers in the brain from the sudden acceleration or deceleration resulting from the injury to the head. Often victims have no memory of events preceding the injury or immediately after regaining consciousness with worse injuries causing longer periods of amnesia Contusion. It appears as softening with punctate and linear hemorrhages in crowns of the gyri and can extend into the white matter in a triangular fashion with the apex in the white matter. Old contusions appear as brownish stained triangular defects in the cortex and underlying white matter. They occur on the orbital frontal surfaces and temporal poles in most instances (Figure 2. The impact of a traumatic head injury is transmitted to the anterior and orbital frontal lobe and to the anterior and mesial temporal lobe. In open head injury there is a fracture of the skull, rupture of meninges, and the brain is penetrated (for instance, a gunshot wound). Speech defects are found in about 60% of the cases acutely and 10% in long term follow-up. Most often the speech defect corresponds to a mixed dysarthria because of the nature of the brain-damage. Aphasia is more frequently found in open head injury because of the focal nature of the injury. For instance, a gunshot in the left temporal lobe most likely will result in a fluent aphasia. Although an overt language defect may not be recognized in a routine clinical examination, specific language testing may show some mild language difficulties; the term sub-clinical aphasia has been used to refer to this mild language impairment that is not overtly observed, but found only with specific language testing. Neoplasms A neoplasm (tumor) is any growth of abnormal cells, or the uncontrolled growth of cells. Primary brain tumors start in the brain, rather than spreading to the brain from another part of the body. A metastatic brain tumor is a mass of cancerous cells in the brain that have spread from another part of the body (Figure 2. The symptoms commonly seen with most types of metastatic brain tumor are those caused by increased pressure in the brain. Brain tumors are classified depending on the exact site of the tumor, the type of tissue involved, benign or malignant (cancer) tendencies of the tumor, and other factors. The overall prevalence rate of individuals with a brain tumor has been estimated to be 221. For instance: seizures, attention difficulties, headaches, and languages changes are common manifestations of brain tumors. Tumors located in the language areas are associated with aphasia-type symptomatology. However, as a general rule, the slower the growth of the tumor, the milder the symptomatology. Although there are different types of tumors affecting the brain, gliomas (tumors originated from the glia) represent close to 50% of all brain tumors. Secondary tumors (metastatic tumors) represent a relative small percentage, close to 10% (Table 2. Percentage of brain tumors Aphasia Handbook 40 Infections An infection appears when the body is invaded by a pathogenic micro- organism. Nervous system infections are frequently secondary to infections in other parts of the body. Acute confusional state is frequently found in cases of brain infections: temporal-spatial disorientation, memory difficulties, naming defects, and psychomotor agitation also are found. It is interesting to refer in particular to two infections: Herpes simplex encephalitis is a severe viral infection of the central nervous system that is usually localized to the temporal and frontal lobes. Herpes simplex encephalitis is thought to be caused by the retrograde transmission of virus from a peripheral site on the face, along a nerve axon, to the brain. The virus lies dormant in the ganglion of the trigeminal cranial nerve, but the reason for reactivation, and its pathway to gain access to the brain, remains unclear. Most individuals show a decrease in their level of consciousness and an altered mental state presenting as confusion, and changes in personality. Intracerebral abscess results from the invasion of infectious organisms into the brain tissue. It is a consequence of the spread of contiguous infection from nonneural tissue, the result of hematogenous introduction from a remote site, or direct mechanical introduction as a result of penetrating trauma or a surgical procedure. A wide range of microorganisms have been recovered from intracerebral abscesses, including most types of bacteria and certain types of fungi and parasitic organisms (Figure 2. An intracerebral abscess can result in a focal symptomatology: when located in the brain areas supporting language, and aphasia manifestations will be evident. Degenerative conditions A degenerative condition refers to a disease in which the function or structure of certain tissues or organs will progressively deteriorate over time. The specific language characteristics in different types of dementia will be examined in Chapter 8 ("Associated Disorders"). One or more of the following cognitive disturbances: (a) aphasia; (b) apraxia; (c) agnosia; (d) disturbance in executive functioning. The cognitive deficits in criteria A1 and A2 each cause significant impairment in social or occupational functioning and represent a significant decline from a previous level of functioning. Language disintegration follows a particular sequence: initially, word-finding difficulties and anomia are found, associated with difficulties in understanding complex language; active and passive vocabulary progressively decreases. Semantic paraphasias (semantic substitutions such as "table" instead of "chair") become more and more abundant. Later on in the disease evolution, phonological paraphasias (phonological substitutions due to phoneme additions, omissions or substitutions) also are observed. However, some language abilities may remain intact even in advances stages of dementia. People with primary progressive aphasia may have trouble naming objects or may misuse word endings, verb tenses, conjunctions and pronouns. Symptoms of primary progressive aphasia begin gradually, frequently before the age of 65, and tend to worsen over time. In progressive nonfluent aphasia, agrammatism (impairment in use of grammatical and syntactic constructs of language), phonological paraphasias, apraxia of speech, and articulatory difficulties are found. In semantic dementia, word-finding difficulties, anomia, impaired comprehension and more verbal paraphasias are observed. For instance, Ardila, Matute and Inozemtseva (2003) reported a case of a 50-year-old, right-handed female who, over approximately two years, presented with a progressive deterioration of writing abilities associated with acalculia and anomia. The ability to read words was preserved, but the ability to read pseudowords was lost. However, in these two conditions there is a subcortical dementia characterized by slowness in cognition, retrieval defects in memory, and executive functioning defects. In general, decreased verbal fluency, difficulty in the comprehension of complex commands, and wordfinding difficulties (anomia) are identified. In other degenerative conditions, speech and language impairment also may be observed. This disease belongs to a group of disorders known as motor neuron diseases, which are characterized by the gradual degeneration and death of motor neurons. Dementia, however, has been occasionally reported (problem solving, attention, memory, naming defects). Summary Any abnormal condition affecting the brain areas involved in language processing can result in aphasia. The specific symptoms of the language impairment depend upon the particular brain area that is affected. Pathological conditions affecting the posterior frontal areas of the left hemisphere usually result in a nonfluent disorder of language, characterized by agrammatism with an accompanying apraxia of speech, whereas pathological conditions affecting the temporal and partially the parietal lobe in the left hemisphere are associated with disturbances in language understanding, word-finding difficulties, and paraphasias. Different etiologies of brain damage are recognized, but the vascular disorders and traumatic brain injury represent the two major causes of aphasia. Brain tumors, infections, and some degenerative conditions also may be associated with aphasia. Progressive Agraphia, Acalculia, and Anomia: A Single Case Report Applied Neuropsychology, 10, 205-214 Grossman, M. Prevalence estimates for primary brain tumors in the United States by age, gender, behavior, and histology, NeuroOncology, 12. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation, 115, e69-e171 Aphasia Handbook 46 Chapter 3 Linguistic analysis of aphasia Introduction Aphasia is the loss or impairment of language function caused by brain damage (Benson & Ardila, 1996). In the previous chapter, the brain damage (neurological dimension) potentially associated with aphasia was reviewed. In this chapter, the specific language disturbances (linguistic dimension) observed in aphasia will be reviewed. There are different communication systems and consequently, different types of language: sign language, animal languages, computers languages, etc. Tongue is the specific verbal communication system characteristic of a human community (for instance, English, Spanish, Chinese, etc).

Purchase 10mg rizatriptan amex. Indian Treatment For Back pain.